Many Europeans hold exclusionary and restrictive notions of national identity, which set high barriers to the acceptance of immigrants in national societies. Until recent years, however, relatively few acted on these notions by voting for parties with restrictive positions on immigration.

This relationship now seems to have changed, with increasing success for the far right. What has caused this change? Our recent research provides an answer.

As right-wing vote shares increase, public debates and parties alike have addressed counter-strategies. Mainstream parties have increasingly tried to win back the support of their electorates by adopting particularly anti-immigrant and nativist positions.

This strategy is however likely to backfire. This is because, as immigration becomes more politicised through this adoption by mainstream parties, national identity becomes more important in voting—and this benefits far-right parties in particular, because of the prevalence among voters of exclusionary notions of national identity.

Activating national identities

To better understand what connects exclusionary notions of national identity with vote choice, we investigated how and when these identities become behaviourally relevant in voting decisions.

Our main argument concerns the role of the rhetoric used by all political elites in a country. If elites adopt more exclusionary positions, they draw attention to immigration and nationalism, which, in turn, should increase the relevance of national identity in the electoral process. Especially during election campaigns, political elites are key players in framing national discourses. Picking up on anti-immigrant and pro-national positions thus creates hostile public debate. This hostile climate ends up strengthening the relationship between national identity and the likelihood of voting for a far-right party.

Put differently, elite political discourse renders national identity more behaviourally relevant. In line with works from social psychology which suggest that external factors activate identities to guide behaviour, hostile political discourse focuses attention on the boundaries of the national in-group. This, in turn, increases the likelihood of voting for nationalist parties.

Testing the relationship

To test whether the relationship between exclusionary national identity and far-right voting is conditional on its prior activation through increasingly exclusionary political elite discourse, we used data from the ONBound project. That project combined harmonised, individual-level survey data from (inter alia) the International Social Survey Programme (ISSP) and the European Values Study (EVS).

Using the membership-boundary questions from both survey programmes, we found that different notions of nationhood are present in all European countries. Importantly, a striking 53 per cent of respondents hold an exclusionary national identity, which sets high barriers to accepting others as part of their national in-group. We used PopuList‘s ‘far-right’ classification to identify whether respondents had far-right voting preferences.

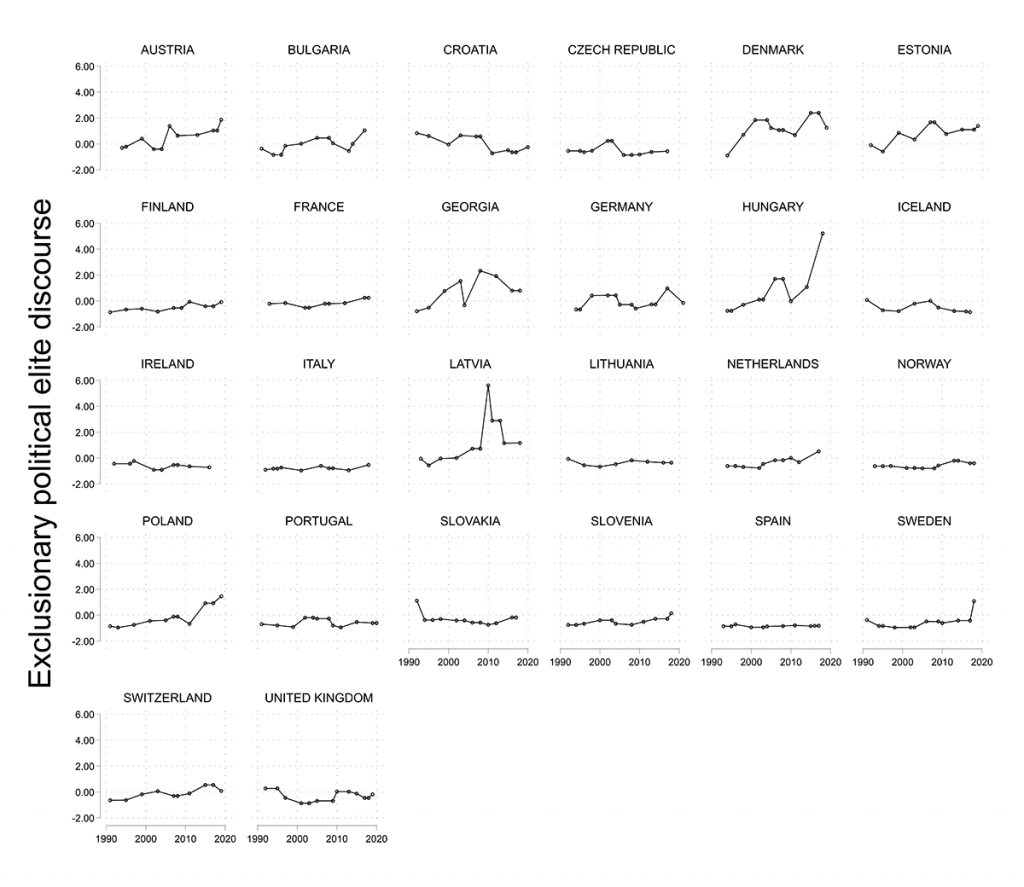

To measure exclusionary political elite discourse, we used data from the Comparative Manifestos Project (CMP). The CMP provides quantitative content analyses of election manifestos for parties competing in democratic elections, including European Union member states.

To measure exclusionary positions, we combined two items from the CMP data: positive statements about a national way of life and negative statements about multiculturalism. The final measure takes the values of the two items (per party, per election), weighted by the party’s vote share. This was done to account for the fact that the more prominent a party is, the more prominent its arguments are in the national discourse.

We then combined these two datasets, based on wave and country, to produce a longitudinal comparative dataset of over 127,000 individuals over 26 years and across 26 countries.

Voting for the far right

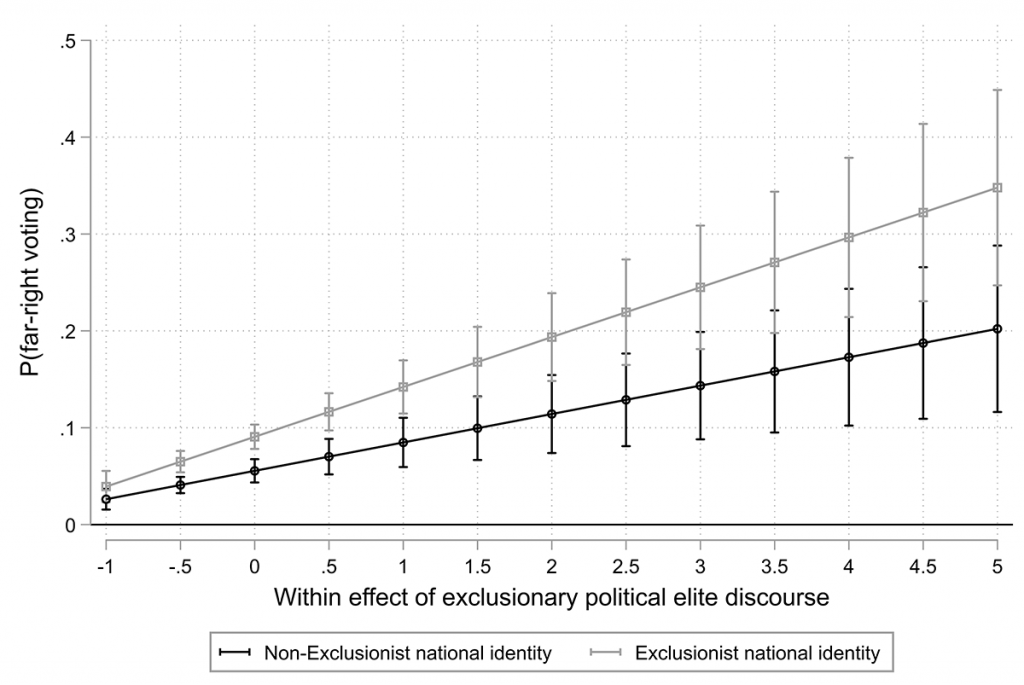

To test our activation hypothesis, we employed longitudinal, fixed-effects models based on individual-level data and within-country estimators on the national level. Our findings reveal that, first, national identity correlates with voting for the far right. Secondly, when political elites—of any party—become more exclusionary, people are also more likely to vote for a far-right party.

Crucially for our argument, both aspects also interact. When political elites take more exclusionary positions, voters who hold more narrow notions of national identity are likely to go on to express a significantly stronger preference for a far-right party than when such rhetoric was not widely promoted.

Our analysis shows that a voter’s ideas about who counts as a compatriot and political elites’ rhetoric both influence far-right voting preferences. It also reveals that the combination of these two aspects is particularly powerful. In other words, such exclusionary political elite discourses invoke, for the voter, nativist images of their nation.

Unintended consequences

The likelihood of voters shifting towards far-right parties increases significantly when political elites across parties adopt exclusionary rhetoric. This is especially true among those who uphold narrow conceptions of national identity.

Thus, rather than attracting far-right voters by adopting more right-wing positions, mainstream parties seem to be strengthening their far-right competitors yet further. In so doing, they are likely to hurt, first and foremost, themselves.

This article was originally published at The Loop and is republished under a Creative Commons licence