The war in Ukraine has drawn attention to the importance of a politics of prevention when it comes to trade in general and the arms trade in particular. This should take into account the records on human rights and democracy of governments’ commercial partners.

The European Union has long striven to strengthen control of arms exports, at the national and EU levels. In 1998 the Council of the EU approved a Code of Conduct on European Arms Exports, which became a Council Common Position a decade later.

Eight criteria thereby orient member states. The second particularly concerns respect for human rights in the country of final destination as well as respect, by that country, for international humanitarian law. Principles of responsibility, prevention and accountability are mentioned in the preamble and inspire the overall stance, enforced at the national level.

Each member state has its own regulations on arms exports. These have distinct characteristics—some more strict, other more flexible or export-oriented. Assessed on the strictness of the criteria, the role of parliament and transparency, sanctions and controls, Sweden, Germany and Italy have a tradition of more stringent and prescriptive regulations. France and the United Kingdom (considered here pre- and post-Brexit) are more pro-export, despite deep differences in their relationships between the state and the arms market.

Legislation can work

Have these regulations at the national and EU levels affected EU arms-export practices? And have member states taken into account the human-rights records of the importing countries?

These questions can be answered using two main sources: the arms transfers database of the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (which calculates trend-indicator values of exports of conventional major weapons systems) and Freedom House (which calculates degrees of freedom and civil and political rights, hence classifying countries as ‘free’, ‘partially free’ or ‘not free’). Combining them, the values and percentages of arms exports to ‘not free’ countries can be calculated, at national and EU levels.

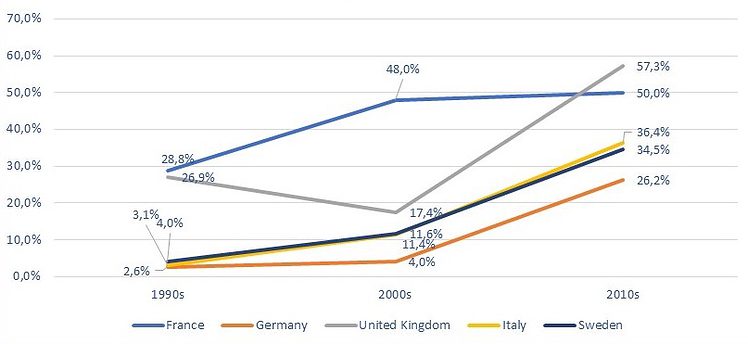

The arms market in the EU is very concentrated: the UK, France, Germany, Italy, Sweden, Spain and the Netherlands supply 94 per cent of EU arms exports. Figure 1 shows the trend for five countries in the three decades to 2020.

Figure 1: percentage of conventional arms exports to ‘not free’ countries from five European countries

In the 2010s, two of these six countries exported at least half of their global arms exports to ‘not free’ countries: the UK (57 per cent) and France (50 per cent). This proportion was lower for the other main EU exporters: Italy (36.4 per cent), Sweden (34.5) and Germany (26.2). Those countries with stricter arms-export controls thus send lower shares of arms to countries violating human rights. This might indicate that such legislation can work.

Market fundamentalism

Comparing the last decade with that from 1990, all the states analysed however increased the proportion of exports to countries with poor human-rights records over the period. Italy’s share to ‘not free’ countries rose from 3.1 per cent in 1990-2000 to 36.4 per cent in 2010-2020, Sweden’s from 4 to 34.5 per cent and Germany’s from 2.6 to 26.2 per cent. Starting from a higher base, the increases were not so marked yet still substantial for France (28.8 to 50 per cent) and the UK (26.9 to 57.3 per cent).

True, the number of ‘not free’ countries designated by Freedom House has risen constantly since 2006. And the outbreak of conflicts involving states with high spending capacity but low human-rights records has increased the demand for armaments, satisfied in significant measure by EU member states.

But all the countries analysed have also been subjected to a process of ‘marketisation’ and associated easing of arms exports in recent decades, intertwining with Europeanisation and globalisation. There has been a ‘secularisation’ of the arms market via a neoliberal narrative based on market fundamentalism, which has interpreted social justice and respect for human rights as a consequence of unregulated competition. This marketisation, reflected in the increasing influence of economic variables at the expense of ethical and strategic concerns, has been identified by scholars in several EU countries, including Sweden, Italy, the UK, Germany and France.

Distinctive identity

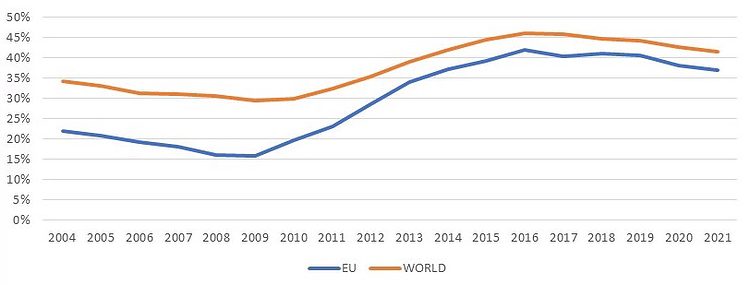

Yet, despite the rising trend of arms exported to ‘not free’ countries, the EU is more attentive to human-rights records than is the rest of the world. In Figure 2 the blue line indicates the share of EU arms exports between 2004 and 2021 going to ‘not free’ countries; the orange line charts the same ratio for the destination of world arms exports.

Figure 2: seven-year simple moving averages of EU conventional arms exports to ‘not free’ countries (as % of EU arms exports) and world conventional arms exports to ‘not free’ countries (as % of world arms exports)

Both follow a rising trajectory but the EU ratio is always lower. The distance between the two lines indicates the value the EU adds in attention to human rights and democracy in this arena—the gap represents what distinguishes the EU from the rest of the world.

The EU has a distinctive identity with regard to attention to human rights. And arms-export controls, if formulated strictly, can be effective and reduce arms exports to countries with poor human-rights records or scant respect for democracy. The aim is to achieve universality beyond any dichotomy or double standard.

Even strict regulations are however not used enough. Strengthening them could enrich the EU toolkit to promote democracy and human rights, reinforcing the union’s identity and working toward rebuilding the fabric of arms control. This is an essential step towards a peaceful international system.

A fuller version of this argument is available in European Foreign Affairs Review