The employment fallout of Covid-19 has been a story of two types of service work. Office-based knowledge workers have largely kept their jobs and incomes while participating in the huge and apparently successful ad hoc social experiment of working from home. Client-facing service workers have borne the brunt of the lockdowns and the steep declines in demand for in-person services in restaurants, hotels, leisure and the arts.

The upshot is that, unlike the ‘mancession’ following the global financial crisis, the first impacts of the pandemic have fallen disproportionately on low-paid female workers. But to see this in the statistics, we must start by looking beyond the unemployment rate.

It is now a commonplace that unemployment has risen only modestly in the European Union since the onset of the pandemic. The EU27 rate stands at 7.5 per cent, less than a percentage point higher than its pre-crisis low. In some member states, notably Italy, unemployment declined sharply in the second quarter (Q2) of 2020, even as coronavirus-related mortality peaked.

But we should not be reassured by the headline labour-market data. The unemployment rate, our customary indicator of labour-market health, has been particularly inadequate to calibrate the effect of the pandemic on employment for European workers.

A higher proportion of workers have moved into inactivity than into unemployment, leaving the labour market—and so the unemployment statistics—altogether. Many workers benefiting from temporary lay-off and short-time working schemes, due to business closures, remain officially employed but have not worked for much of the last year. They also remain at greater risk of unemployment when normal life resumes, as not all employers will be in a position to reopen shuttered businesses. And even for those who have continued working since March 2020, average working hours have decreased in line with an inevitable damping down of economic activity induced by lockdowns.

Truer picture

So what metrics should we use to get a truer picture? Eurofound has looked in detail at three measures in the EU Labour Force Survey quarterly data:

- the decline in headcount employment,

- the share of employees indicating not having worked any hours in the reference week in Q2 2020 and

- the decline in average weekly working hours of those who did indicate having been working.

According to the first measure, we see already that EU27 employment was around 6 million lower (just over 3 per cent) in Q2 2020 than would have been anticipated, based on trend growth. In the first flush of the pandemic—just one quarter—as many jobs were knocked out as the global financial crisis did for over two years.

The second and third measures capture shifts on the intensive margin—the labour inputs of those who remain employed. The second measure is a proxy for furloughed workers—those whose jobs were ‘put on ice’ as a result of lockdowns and where the state intervened to support income via pandemic unemployment benefit, temporary lay-off or short-time working schemes. And it is here that the most dramatic impacts of the crisis during the first wave of Covid-19 are revealed.

The customary share of EU workers not working in any week in Q2 2019—due to annual leave, sickness and so on—was around 7 per cent. This more than doubled to 17 per cent during Q2 2020: one in six workers were not working in that second quarter. Those who were were working on average one hour less per week.

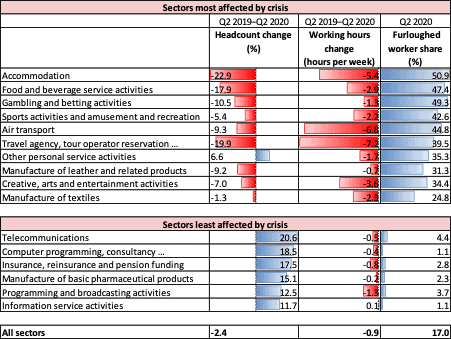

The sector-specific impacts of these shortfalls were very unevenly spread, as the table illustrates.

Sectors most and least affected by the Covid-19 crisis: EU27, Q2 2019 – Q2 2002

Accommodation, which includes hotels and other holiday accommodation, has been most affected by declines in labour inputs during the crisis: employment contracted in the sector by nearly a quarter in the 12 months to Q2 2020. Just over half of the remaining workers were on furlough in a given week during the quarter, and those who continued to work worked on average 5.4 hours fewer than customarily. Taken together, these data imply around a two-thirds reduction in paid work hours.

More broadly, hospitality, travel and sports or leisure-related activities—all heavily reliant on physical proximity—suffered the biggest contractions in hours worked and employment. And while the most important factor in this contraction overall was the furloughing of workers, job loss was clearly important in accommodation, food and beverages and travel agencies. In these sectors, extensive recourse to furloughing may have saved some vulnerable jobs but not all—around one in five jobs disappeared between Q2 2019 and Q2 2020.

More knowledge-intensive service sectors were, though, less affected by the pandemic than the person-to-person sectors. There was robust headcount expansion and less recourse to furloughing in telecommunications, computer programming and consultancy, broadcasting and information-service activities. Employment resilience was supported by the ‘teleworkability’ of much work in these sectors.

Quite distinctive

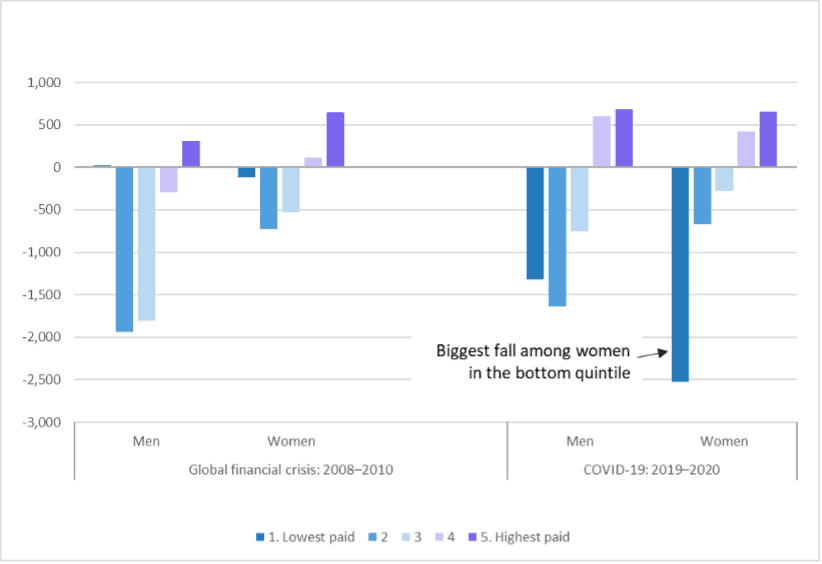

The global financial crisis of 2008-10 provides an interesting comparison. Then too, well-paid work was comparatively sheltered from the worst effects of recession: employment continued to grow in the jobs that constitute the best-paid 20 per cent of employment, with in both periods more than one million net new jobs created (see figure).

Net employment losses have proved, however, quite distinctive. During the global financial crisis, the sharpest losses were in the middle of the job-wage distribution, with the lowest-paid jobs relatively unaffected. But during the Covid-19 pandemic, employment falls have been sharpest in low-paid jobs.

Comparing the global financial crisis and the first phase of the Covid-19 crisis: employment shifts, by gender and job-wage quintile (thousands)

The differential sectoral impacts of the two crises go a long way to explain this. The global financial crisis affected first and foremost manufacturing and construction—male-dominated, mid-paid sectors. As we have seen, the pandemic has primarily affected service sectors involving high social contact, many of which employ more women than men and where average pay tends to be low. This is reflected in the right-hand panel, in the sharp contraction of bottom-quintile employment for women.

In summary, while the global financial crisis triggered a ‘mancession’, with two male jobs lost for every female, the Covid-19 crisis has been more balanced in its employment loss in terms of gender—but this has been felt most sharply by women working in low-paid service sectors.

Higher-paid service workers have fared much better across all labour-market outcomes. The shelter of telework has been an important dimension of this resilience but access to this shelter is very much task-dependent.

Computer-facing, knowledge-based work can shift into the home but much in-person service work is still difficult to perform at a distance or virtually. One divide made stark during the crisis—but likely to persist beyond it—is that between ‘remotes’, whose work lends itself to telework, and the remainder, including many ‘essentials’, for whom telework is largely not an option.

See all articles of our series on the role of women in the coronavirus economic crisis

John Hurley is a senior research manager in the employment unit at Eurofound.