Europe stands at a crossroads. Strategic dependencies, technological disruptions, fiscal constraints and an increasingly volatile geopolitical landscape have created a perfect storm of challenges. If Europe wants to preserve its prosperity model for future generations, it requires bold economic policy responses to these dynamic developments. The continent needs a forward-looking industrial policy that drives productivity, accelerates innovation and, crucially, places workers and their concerns at the centre of navigating these turbulent times.

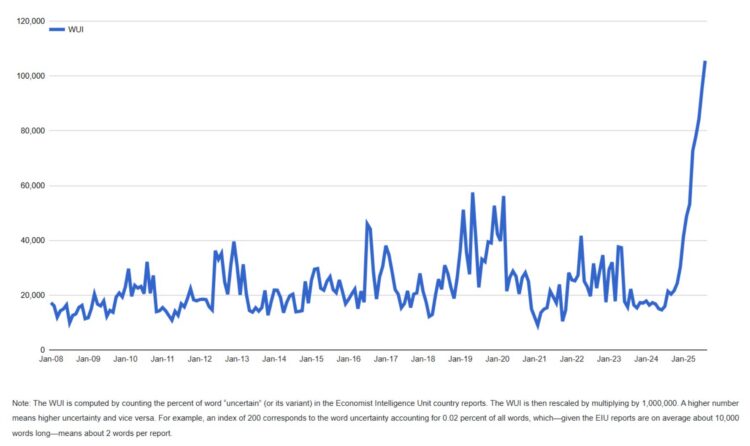

Uncertainty has become the defining characteristic of today’s global economy and poses a fundamental challenge for European policymakers. Growth remains anaemic, inflation proves stubbornly persistent, and escalating trade tensions threaten the export-dependent European economy. Simultaneously, the European Union must finance its ambitious green and digital transformation while managing geopolitical risks emanating from Ukraine and the Middle East. Policymakers must therefore navigate a treacherous path between stabilising growth, driving transformation and managing unprecedented uncertainty. The World Uncertainty Index, derived from text analysis of Economist Intelligence Unit reports spanning 143 countries, reveals how profoundly unpredictability now shapes the economic landscape—and underscores why forward-looking industrial policy has become essential to confronting it.

Figure 1: World Uncertainty Index, https://worlduncertaintyindex.com/

The imperative for active European industrial policy

The growing chorus calling for a more proactive European industrial policy to drive the “twin transformation”—the parallel green and digital transitions—marks the revival of strategic industrial thinking, catalysed by the existential challenges of climate change and digitalisation. This fundamental reorientation demands forward-looking policies that deliver planning security, ensure fairness and embrace the transformative ambition of a green industrial revolution. Intensifying geopolitical rivalries, particularly the strategic competition between the United States and China, have shifted European focus toward economic security and global competitiveness.

To avoid “five lost years” in Europe’s green transition, policymakers must approach the twin transformation as an inherently political project. Success requires balancing climate action, digital innovation and social equity through an inclusive industrial policy that meaningfully engages workers, civil society and other stakeholders in shaping the transition.

The successful implementation of the green industrial revolution hinges critically on state capacities—the institutional and administrative capabilities that enable governments to anticipate, design, steer and evaluate policy effectiveness. Currently, public institutions often lack the capacity and capability to manage the transformation process effectively. Control systems across the EU suffer from significant shortcomings, including weak leadership, insufficient resources and inadequate implementation capabilities.

These deficiencies became starkly apparent in the sluggish rollout of the Just Transition Initiative, which encountered institutional capacity bottlenecks and suffered from an absence of comprehensive, forward-looking regional planning. At the level of EU innovation agencies, administrative overload and excessive risk aversion stifle radical innovation. Addressing these weaknesses requires fundamental governance reform. This means strengthening administrative capacities at national and regional levels while improving coordination between innovation agencies. Policymakers must cultivate dynamic capabilities, develop organisational ecosystems that foster innovation, and demonstrate greater tolerance for risk and experimental approaches. Ultimately, the transition to a climate-friendly economy demands the evolution of a “learning state” capable of adapting to rapidly changing circumstances.

Accelerating transformation while ensuring social justice requires industrial policy to deploy targeted interventions on both supply and demand sides. Supply-side instruments propel innovation and green sector growth through measures including training grants, employment foundations and targeted industrial strategies such as the Net Zero Industry Act. An active state remains essential to catalysing these innovations. Demand-side instruments, meanwhile, harness public procurement, regulation and price signals like carbon taxes to create markets for climate-friendly products. Large-scale EU investments in rail infrastructure, electrified transport and localised production further stimulate green demand. The central political challenge lies in implementing these measures swiftly and effectively, particularly through procurement and competition policies.

Transforming public procurement from legal constraint to strategic tool

Public procurement—the purchasing of goods and services by governments—represents one of the most powerful policy instruments available to the public sector. Accounting for nearly 14 per cent of European Union gross domestic product, approximately €2 trillion annually, it shapes markets, signals priorities and possesses the potential to create demand for transformative innovation. Public procurement aligned with a coherent industrial strategy provides a crucial lever for deploying public spending in harmony with the EU’s economic and climate objectives.

The EU’s public-procurement framework constitutes a dense, multilayered legal regime built upon two overarching principles: preventing spiralling costs for taxpayers and combating corruption through transparency within a strict procedural framework. Three directives govern the award of concession contracts. They promote using “most economically advantageous tender” criteria, which aim to secure best value by considering quality, environmental and social factors, lifecycle costs and innovation potential. However, constrained by this tight corset of rules, national authorities still predominantly award contracts based solely on lowest price, undermining strategic goals. Over 60 per cent of contracts in the EU are awarded on price alone.

In 2025, the Commission unveiled a roadmap to reform the EU’s procurement framework, focusing on two priorities. First, expanding joint procurement to build strategic stockpiles of critical raw materials through the forthcoming Industrial Decarbonisation Accelerator Act, revision of procurement directives and establishment of a new EU Critical Raw Materials Centre. Second, extending and simplifying binding non-price criteria, including minimum EU content requirements. These criteria aim to create lead markets, with energy-intensive sectors targeted initially.

Introducing binding non-price criteria into procurement processes can generate positive environmental and social spillovers, but these benefits carry costs. Public authorities face pressure to deliver value for money, reduce deficits and avoid actions that might fuel inflation, such as paying premiums for goods and services, particularly for large-scale infrastructure or energy projects. Moreover, attempting to align public procurement with multiple, sometimes conflicting objectives may result in extended procurement timelines, reduced competition, increased administrative burden and higher government costs. Similarly, eligibility filters can rapidly reshape supply chains but may create entry barriers—a dilemma some scholars have termed the “DAS trilemma”.

Two main pathways can reconcile these competing objectives. In the short term, pooling demand through joint EU procurement and reducing procedural hurdles can lower costs. Simplifying regional contracting and introducing de minimis rules—exempting small projects from public procurement procedures—can boost participation by small and medium-sized enterprises. In the long term, the public sector can serve as an anchor of demand, providing predictable procurement volumes that justify private investment—an approach reflected in the EU’s “lead market” strategy. Measures like Buy European clauses and common industrial standards help scale up EU industry and offset early investment costs. Above all, lead market creation must support decent work: tackling wage and social dumping through general contractor liability and shorter subcontracting chains ensures fair conditions and broad worker identification with the twin transition.

The transformation toward a sustainable and resilient economy demands an active industrial and economic policy that transcends merely correcting market failures to actively shape markets themselves. A proactive public sector that coordinates and implements both supply-side and demand-side instruments to guide innovation, investment and production toward socially and ecologically desirable outcomes is essential to achieving a green and digital industrial revolution. By aligning public action with private initiative, the state becomes a market-shaping force that steers the economy toward long-term goals including decarbonisation, technological sovereignty and social inclusion. Only through such coordinated and forward-looking governance can transformation succeed as a collective process rather than a fragmented or purely profit-driven adjustment.