The problem. New technology, like all technological improvements since the Industrial Revolution, aims to replace human labor with machines, broadly understood. In that sense, Artificial Intelligence (AI) is not different from the self-acting mule introduced in the cotton industry in the 1820s: it replaces human labor although now it does it at a higher level of human skills. (In many ways, such developments were forecast because there was historically an inexorable increase in the level of skill of labor that was replaced by machines, beginning with unskilled and repetitive tasks performed by enslaved labor and then rising ever higher.)

From the distributional point of view, the issue is that substitution of labor by capital leads to the larger share of national income accruing to capital. This, translated in terms of actual persons who receive such income, means that entrepreneurs and inventors of new machines and investors in such new technologies gain disproportionately. Investors, by definition, are people who own capital and who belong to the top strata of income distribution. Thus, the expansion of the capital share almost necessarily translates into an increase in overall income inequality.

This naturally raises the question: what policies should be used to stop or moderate the increase in income inequality? There are three ways in which this can be done: spreading the ownership of capital more widely so that the effect of the rising capital share is not felt only at the top, taxing the highest capital incomes more than now, and banning some new financial activities that create income for the participants but are “directly non-productive”.

I shall consider the three options.

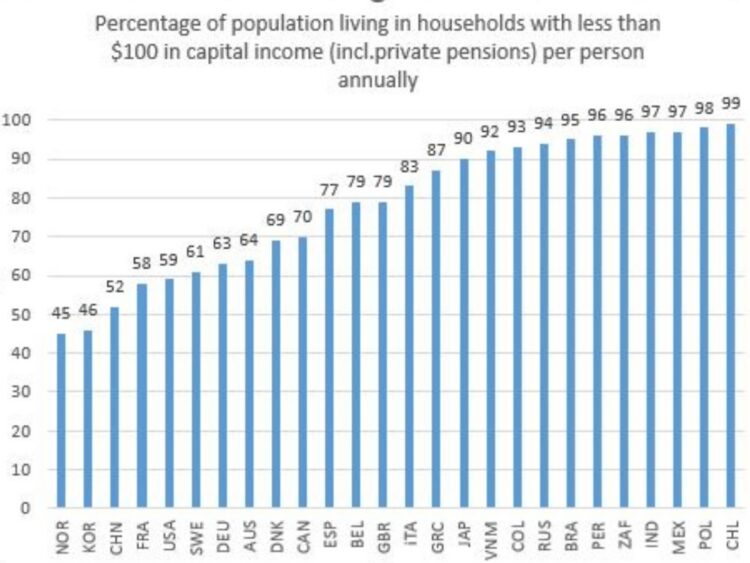

Spread the ownership of capital. Capital is extraordinarily heavily concentrated. The figure below shows that, on average, 77 percent of households in advanced and middle-income economies have zero or close to zero (“close to zero” is defined as $100 per person annually) cash income from capital. It should be noted that capital here includes only financial or productive capital that produces a cash income for its owner. It is not the same thing as household wealth, which also includes owner-occupied housing, jewelry, paintings, furniture, etc. The countries with the highest spread of capital income, that is, with the lowest share of “zero capital households,” are Norway, South Korea, and (interestingly) China. Yet even there, about one-half of households receive no income from capital. In the United States, that percentage is almost 60 percent, and in other advanced countries, it exceeds 70 percent. (I discussed this topic in more detail in my previous Substack piece.)

Source: Calculated from individual household data available in Luxembourg Income Study. The data refer to the most recent surveys, conducted between 2018 and 2023. The average of 77 percent is population-weighted.

The issue with respect to AI is, as mentioned above, the following: if so few people have financial and productive capital, its rising importance will simply accrue to those who already own capital assets, will further empower the already rich, and increase inequality. (It may not increase the number of “zero” households, but for inequality to go up, it is sufficient that it makes those on the top even richer).

How to spread capital ownership? The issue has been addressed before with scant results. Margaret Thatcher spoke of “people’s capitalism.” It ended mostly as privatization of council housing. Employee Stock Ownership Plans (ESOP) in the United States were another way to help ownership spread to workers. Their results were also small, but as Isabel Sawhill argued, it was principally because giving stock to workers was not fiscally encouraged: if companies enjoyed tax benefits when they distributed stocks to workers, there would probably be more ESOPs. In fact, there is no obvious reason why CEOs should be paid in company shares but not workers. In some countries, private pension funds were used not only to get rid of potentially fiscally unsustainable defined-benefit systems but also to spread income from capital. In the above graph, for example, the share of “zeros” in the UK decreases from 84 percent to 79 percent when income from private pensions is included. All of these methods could be used with a distinct objective of spreading some capital ownership to more people and thus moderating the increase in income inequality that would quasi-automatically follow from greater application of new technologies, including AI.

Tax highest capital incomes. Another rather obvious way to check rising inequality from capital is to tax it. This is often seen as the only solution, but, as I implicitly argued above, taxation should be a solution, but only one among several. Not every problem can be solved by taxation. Capital incomes are, paradoxically, currently taxed in the United States at lower rates than equivalent labor incomes: for example, the marginal tax rate on labor income under $100,000 annually is 24 percent vs. 15 percent for capital; for incomes over $400,000 the gap is even greater: 35 vs 15 percent; see also the forthcoming excellent book by Ray D. Madoff The Second Estate: How the Tax Code Made an American Aristocracy. There is therefore lots of space to increase taxes.

Another method, in many ways equivalent to taxation, is explicit government ownership in new technologies or innovations where government funding played an important role—where, in fact, the government might have been the “angel investor.” Such contributions often go unrecognized. Mariana Mazzucato has documented it persuasively in the case of many US Silicon Valley companies. The same thing is probably going on today, and governments should not be shy in asserting their right to some of the capital income flows. The US government’s decision to take a significant stake in Intel can be seen in this light. Such explicit government ownership is even more easily justified in countries like China, where, directly and indirectly, the role of the government in helping innovation is even greater.

Ban some noxious new technologies. A final way to stop new technologies from exacerbating inequality is to simply ban some activities of a speculative nature that are directly “non-productive.” This is clearly the most difficult and the most radical way to deal with the problem and should be used extremely cautiously. However, it should not be excluded. What is a “non-productive” activity in economics is difficult to establish. In theory, every activity and thus income from that activity based on voluntary transactions between economic actors is justified. But in practice there are limits. Drug or arms sales are in many countries banned even if both can definitely be seen as activities taking place voluntarily between economic agents. With new technologies, there seem to be activities (linked with cryptocurrencies and financial speculation in general) whose sole objective is speculation. They do not increase the quantity of goods or services, nor do they obviously improve the allocation of resources. Many such activities are more like lotteries: they make some rich while impoverishing many. In fact, as Adam Smith, in a little-noticed passage, noted more than 250 years ago, the greater the lottery, the greater the number of losers. The option of bans should not be left off the table. It should, however, exercised judiciously and only in extreme cases where, for example, taxation is difficult or the activity is sufficiently “noxious” or replete with negative externalities so that its ban can be justified.

It is by doing these three things simultaneously, albeit in different proportions at different times, that the government may hope to keep the increase in inequality within acceptable bounds while not dissimulating innovation and the introduction of new technologies.

First published on Branko Milanovic’ Substack

Branko Milanovic is a Serbian-American economist. A development and inequality specialist, he is visiting presidential professor at the Graduate Center of City University of New York and an affiliated senior scholar at the Luxembourg Income Study. He was formerly lead economist in the World Bank's research department.