The European Union budget is in urgent need of reform. It is not up to the challenges the EU is facing—neither its envelope, which despite the growing challenges has been limited to about 1 per cent of EU gross national income (GNI) in recent decades, nor its structure of expenditures and revenues.

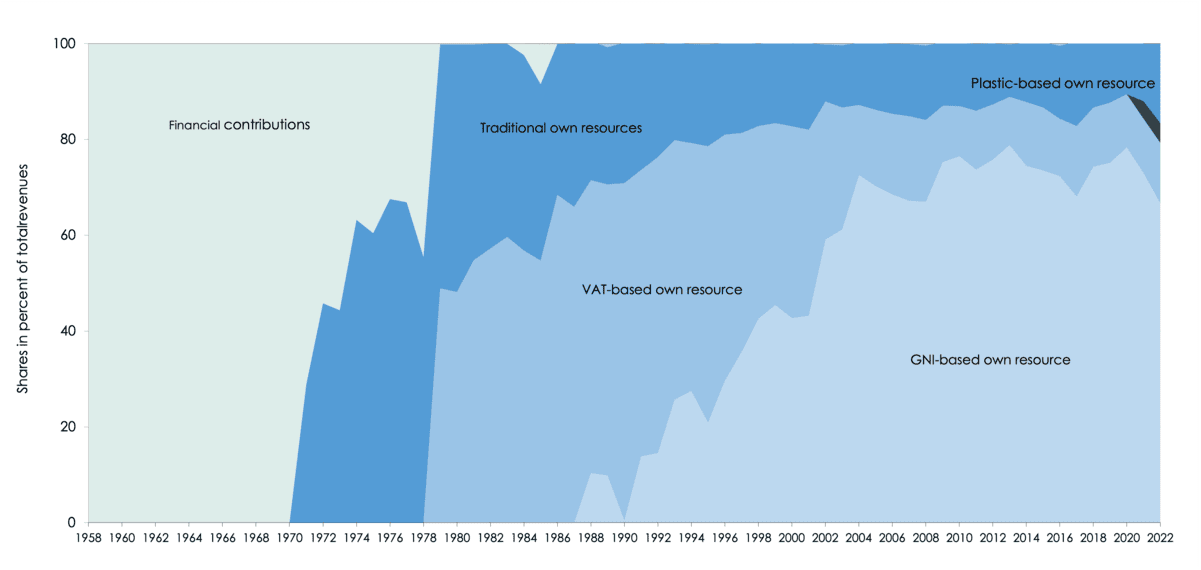

The revenue-side system of EU ‘own resources’ can hardly be characterised as future-oriented. It is dominated by member-state contributions based on value-added tax (VAT-based own resource), gross national income (GNI-based own resource) and, since 2021, non-recycled plastic waste (plastic-based own resource). Their combined share in total own resources (excluding other revenue) has been growing in the long run, reaching 83.4 per cent in 2022. In contrast, traditional own resources, which represent genuine own resources based on EU policies and comprise customs duties levied at the EU’s external border, have been continuously diminishing in importance over time and amounted to 16.6 percent in 2022 (Figure 1).

Figure 1: composition of EU revenues, 1958 to 2022, excluding other revenue* (total own resources)

With the exception of the plastic-based own resource, which aims to contain non-recycled plastic waste, existing own resources do not contribute to important EU goals. Moreover, the shrinking weight of traditional, genuine own resources implies a low and decreasing financial autonomy for the EU. Not least, financing the bulk of EU expenditures through member states’ contributions fosters a juste-retour perspective among them, more interested in their net positions (the difference between financial contributions and transfers received) than in maximising the added value for the union provided by the budget.

Fundamental reform

More recently, the longstanding debate about fundamental reform of the EU revenue system has gained new momentum. This has stemmed from the need to repay NextGenerationEU debt and for a robust and reliable revenue stream if the EU is to be enduringly credible as a creditworthy issuer of bonds—as well as for emerging potential genuine own resources linked to EU policies.

Innovative new own resources can replace part of the GNI-based own resource and thus shift the financing of EU expenditure away from national contributions to more genuine own resources, while generating the additional revenues required to repay NextGenerationEU debt and expand the very constrained budget envelope. They can not only yield revenues to finance EU expenditure but also address long-term challenges the EU is facing, such as climate change.

In the face of the current crises, and particularly the Russian war of aggression against Ukraine, the mid-term revision of the EU Multiannual Financial Framework (MFF) for 2021-27 was used to make available an additional €64.6 billion of expenditure, of which €50 billion was envisaged for the Ukraine facility. The revision was however concluded in February without agreement on new own resources.

New own resources

When it launched the mid-term review last June, the European Commission updated a proposal for new own resources following an Interinstitutional Agreement in December 2020 (IIA) with the European Parliament and the Council of the EU. To finance the borrowing costs of NextGenerationEU agreed by the European Council the previous July, the IIA offered inter alia a roadmap towards new own resources during the 2021-27 MFF period.

In December 2021, the commission proposed a first basket of new own resources. This would include auctions of increasingly stringent emissions allowances linked to the EU Emissions Trading System (ETS) and a Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) to deter ‘carbon leakage’ beyond the union. It would also tap residual profits from the largest multinational enterprises allocated to the EU under the first pillar of the agreement on minimum corporate taxation arrived at by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development and the G20. A second basket, based on the taxation of financial transactions and of corporations, was to be proposed by the commission by the end of 2023.

The adjusted package proposed by the commission last June revised the original proposal for the first basket of new own resources. It includes three new own resources to be introduced starting this year (Figure 2):

- an ETS-based own resource, consisting of 30 per cent of auctioning revenues from the ETS and yielding €7 billion per year as of 2024 and €19 billion per year as of 2028;

- a CBAM-based own resource, based on 75 per cent of revenues from the CBAM, from which a yearly amount of €1.5 billion is expected as of 2028, and

- an own resource stemming from levying 0.5 per cent on the gross operating profit of corporations, which should generate yearly revenues of €16 billion.

Altogether, this adjusted first basket of new own resources is expected to yield €23 billion annually (from the ETS-based own resource and the temporary statistical own resource based on company profits) as of 2024. As of 2028, the three new own resources proposed in the adjusted first basket would generate yearly revenues of up to €36.5 billion.

Figure 2: proposed new own resources contained in the adjusted first basket

| Own resource | Brief description | Timeframe | Expected revenues in billion euro per annum (2018 prices) |

| ETS-based own resource | 30% of all revenues from emission trading in the EU, including power plants, industry and aviation (ETS1), maritime transport, buildings, road transport (ETS2) | As of 2024 As of 20281 | 74 194 |

| CBAM-based own resource | 75% of revenues from CBAM applying a carbon price from imports from third countries not applying carbon pricing2 to cement, steel and iron, aluminium, fertiliser, electricity | As of 20283 | 1.54 |

| Temporary statistical own resource based on company profits | 0.5% of notional EU company profit base (gross operating surplus of financial and non-financial corporations) | As of 2024 | 16 |

| Total | 2028 to 2030 | Up to 36.5 |

Binding commitment

In the fourth year since the agreement on the IIA, which included a binding commitment to introduce new own resources, not much progress has been made. The adoption of the adjusted first basket of new own resources by the council is still pending, although revenues for the EU budget had been expected, starting with 2024, already. For the reasons indicated above, implementation of innovative new own resources should not be delayed further.

Given the urgency of the climate crisis, green own resources should be a priority. Revenues from the ETS and the CBAM, as proposed by the commission, offer themselves particularly as they are directly related to EU policies that would not exist without union-wide co-ordination. Considering that those policies are already in place, they could be implemented rather quickly. Other potential green sources for the EU budget include taxes on international aviation and shipping or cryptocurrencies, which are associated with negative climate impacts.

In addition, the co-ordinated introduction EU-wide of a progressive wealth tax on wealthy households could reduce tax evasion and generate significant revenue for the EU budget. Substantial revenues could also be collected, as envisaged originally in the IIA, through co-ordinated taxation of financial transactions with low tax rates, which could stabilise financial markets too.

This is part of our series on a progressive ‘manifesto’ for the European Parliament elections

Margit Schratzenstaller is senior economist at WIFO, the Austrian Institute of Economic Research, and has been working in the research group 'Macroeconomics and European Economic Policy' since 2003. Her areas of expertise include (European) tax and budget policy, the EU budget, tax competition and harmonisation, family policy and gender budgeting.