Boomer-bashing has become Germany’s latest intellectual fashion. In his new book “Nach uns die Zukunft” (After Us, the Future), Marcel Fratzscher, president of the German Institute for Economic Research, delivers a sweeping indictment: hardly any generation since the Enlightenment and Industrial Revolution has robbed its children and grandchildren of as many opportunities for a good and self-determined life as today’s baby boomers. The intergenerational contract, he declares, lies broken—that foundational promise that each generation would fare better than the last.

Such fundamental criticism demands serious evidence. Yet Fratzscher’s historical comparison immediately invites scepticism—has he somehow overlooked two world wars? In his book, Fratzscher highlights that 84 per cent of Germans, including the vast majority of baby boomers themselves, believe future generations will be worse off than today’s. He calls this “an alarm signal”. For a scientist, however, it seems peculiar to forecast economic development through opinion polls rather than theories and facts.

The argument collapses under its own logical inconsistencies. Many of the threats Fratzscher identifies—geopolitical and geo-economic conflicts, dangers from technological progress, democracy’s retreat, manipulation by the super-rich—cannot reasonably be laid at the feet of German baby boomers. Moreover, we must ask how much responsibility “boomers”, those born between 1955 and 1969, actually bear for future generations’ welfare. If the intergenerational contract means children should prosper more than their parents, then boomer children, now between 30 and 40 years old, have already succeeded.

The prosperity paradox

The economic evidence tells a strikingly different story from Fratzscher’s narrative. From 1980 to 1991, real gross domestic product per capita in West Germany rose by 17 per cent. Since 1991, it has increased by another 41 per cent across unified Germany. Consider the everyday transformations: four decades ago, long-distance calls were prohibitively expensive, and many people queued at telephone booths because private phones remained a luxury. Access to music was almost unaffordable for poorer citizens—in 1980, an LP cost around Euro 36 in today’s purchasing power.

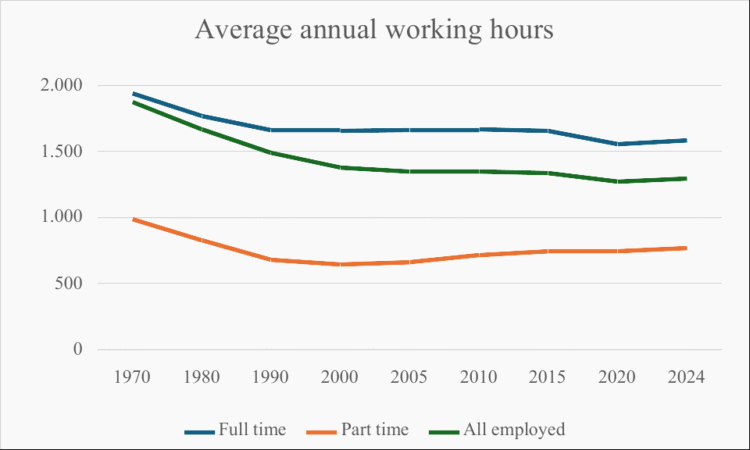

Baby boomers contributed throughout their working lives to creating today’s substantially higher material prosperity. In return, they accepted longer working hours than today’s employees face.

Source: Sozialpolitik aktuell

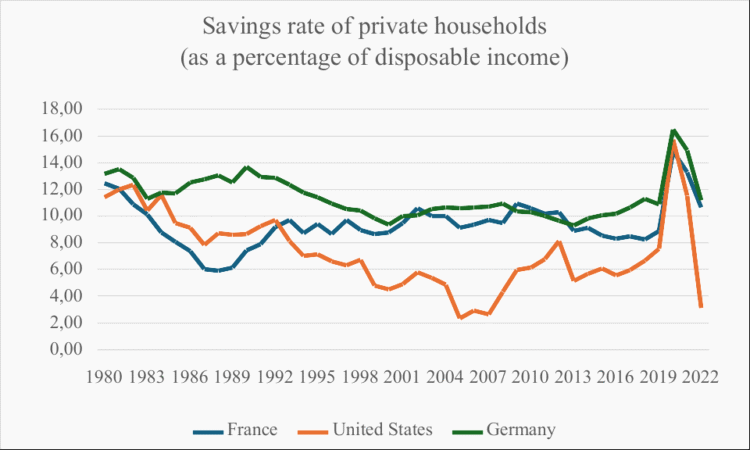

The boomers also saved considerably more than their French neighbours or American households, contradicting claims by Monika Schnitzer, chair of the German Council of Economic Experts, that boomers lived beyond their means.

Source: Destatis and OECD

This fiscal responsibility appears clearly in Germany’s current account balance, which reflects the country’s surplus of income over expenditure. Since 1980, it has shown very high surpluses for the most part. Only between 1991 and 2001 did relatively small deficits appear, directly attributable to German reunification’s extraordinary costs.

Reunification’s forgotten burden

One of the boomers’ historic achievements was accomplishing German reunification. In 1991, approximately 61 million West Germans had to integrate 16 million East German citizens economically overnight, while guaranteeing them the Federal Republic’s high social benefits from day one. Massive investments in eastern Germany’s obsolete infrastructure followed.

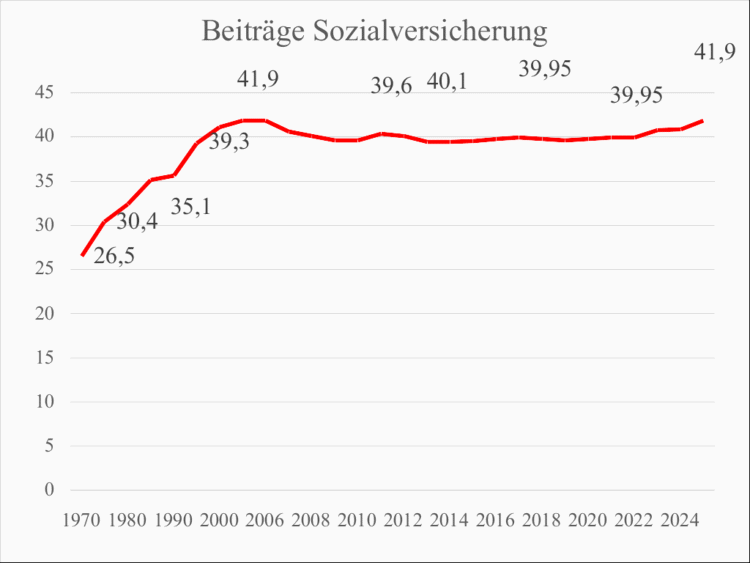

These burdens required extraordinary sacrifice. Income tax rates soared—by 1997, the top rate including the solidarity surcharge reached almost 57 per cent. Social security contributions rose sharply to finance eastern benefits. To suggest, as Fratzscher does, that boomers “basked in the glory of their economic success” amounts to an insult, particularly to low-income workers who bore these costs.

Source: Sozialpolitik aktuell

The baby boomers reaching retirement age will undoubtedly pose considerable financial challenges. Yet the average retirement age has risen significantly from 62.3 years in 2000 to 64.7 in 2023. Simultaneously, the pension level has fallen from 52.9 to 48 per cent. The retirement age will continue rising until 2031.

A golden decade’s legacy

Despite his boomer-bashing rhetoric, even Fratzscher must acknowledge this generation leaves Germany in remarkably good shape. Over the past fifteen years, almost all regions have experienced significant economic growth. “Germany has never had more people in work than it does today,” he admits. “The German economy experienced a golden decade in the years after 2010… Numerous companies made profits. Industrial groups were able to increase their global market shares, and wages also rose significantly in some cases. Despite many prophecies of doom, there is no sign of deindustrialisation as yet.”

Against this backdrop, Fratzscher’s policy proposals appear increasingly bizarre. He suggests introducing compulsory social service for baby boomers after retirement, perhaps in nursing or public service. His “simple solution” would mobilise boomers who completed military service to defend Europe—a proposal already mocked on the satirical “Heute-Show”.

Even more problematic is his proposed “boomer solidarity tax”—a special 10 per cent levy on all income for people over 65. Implementing this consistently would require taxing not only pensions but all income, including assets and company shareholdings. This would violate the fundamental principle of taxation according to economic capacity. Constitutional justification based on Fratzscher’s alleged “breach of the intergenerational contract” seems highly improbable.

Dangerous populism

Fratzscher’s book achieves precisely what he claims to oppose: poisoning welfare state debates with dangerous populism by pitting vulnerable groups against each other. He divides society into “boomers” and their supposed victims. The accusation that boomers have broken the intergenerational contract—a serious charge easily misused in public debate—becomes particularly negligent when based on pure speculation rather than economic facts.

Fratzscher himself acknowledges that exploiting fears brings catastrophic consequences. It polarises society and makes finding compromises and solutions increasingly difficult. Yet his own work exemplifies this very problem, substituting generational warfare for the serious policy discussions Germany needs about pensions, investment, and social cohesion.

The real intergenerational challenge lies not in assigning blame but in recognising how each generation’s contributions and sacrifices have shaped today’s prosperity. Germany’s baby boomers leave a complex legacy—neither the disaster Fratzscher describes nor an unblemished success story. Understanding this nuance, rather than indulging in generational scapegoating, offers the only path towards policies that can genuinely secure prosperity for all generations.

This is a joint column with IPS Journal

Peter Bofinger is professor of economics at Würzburg University and a former member of the German Council of Economic Experts.