Wealth inequality across the European Union represents a growing threat to social cohesion, with profound implications for housing access, educational opportunity and economic mobility. A recent Eurofound report illuminates the true scale of this challenge, revealing disparities that dwarf those seen in income distribution. While economists and policymakers habitually focus on what people earn, wealth tells a fundamentally different story — one that captures not merely today’s earnings but tomorrow’s security, opportunity and resilience against economic shocks.

The distribution of wealth transcends academic concern; it fundamentally shapes social and economic vitality. Societies with highly concentrated wealth risk calcifying into two-tier systems where privileged minorities command advantages in health, education and political influence whilst majorities struggle with diminished prospects. Understanding these disparities therefore becomes essential for constructing a more equitable and resilient European future.

The Haves and Have-nots

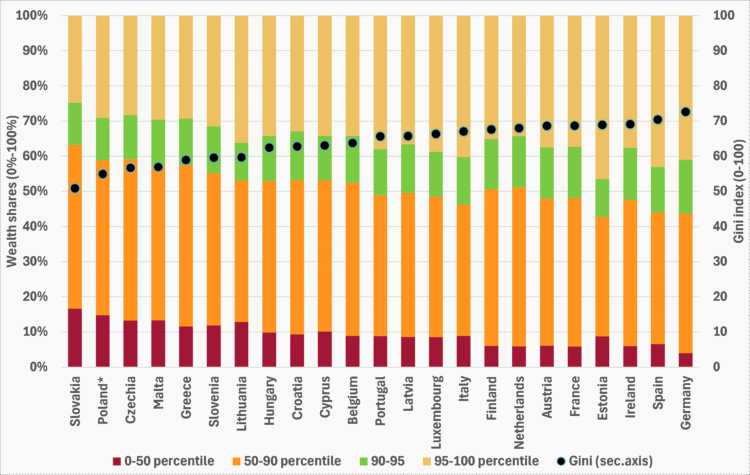

Europe’s wealth gap reveals stark continental divisions that challenge assumptions about prosperity and equality. According to the latest data from 2021 (Figure 1), Germany, Spain and Ireland exhibit the most extreme wealth concentration, with Germany’s Gini index reaching an extraordinary 72.6. Slovakia, Poland and Czechia, conversely, maintain the continent’s most equitable wealth distributions.

These figures dwarf income inequality measures, which typically range from Gini values of 20 to 38 across the bloc. This disparity underscores a crucial reality often absent from public discourse: wealth concentration far exceeds income concentration, creating power imbalances that income statistics alone cannot capture.

The concentration reveals troubling extremes. In Estonia, Spain and Germany, the wealthiest five per cent control more than 40 per cent of national wealth. Germany’s bottom half collectively holds just four per cent of total wealth — a figure that should give pause to anyone concerned about democratic participation and social mobility. Even Slovakia, the study’s most egalitarian nation, sees its poorest half controlling only 17 per cent of national wealth. These statistics represent more than abstract inequality; they embody fundamental imbalances in economic power and life chances.

Beyond the most unequal trio, the top ten features predominantly EU-15 nations: France, Austria, the Netherlands, Finland, Italy and Luxembourg, with Estonia as the sole exception. The rest of the ten most equal countries also cluster in central and eastern Europe or the Mediterranean: Malta, Greece, Slovenia, Lithuania, Hungary, Croatia and Cyprus. This geographic pattern might suggest historical and institutional factors shape wealth distribution, yet a paradox emerges. Countries characterised by high wealth inequality typically possess the greatest absolute wealth, whilst more egalitarian nations tend toward lower overall wealth levels. This correlation raises uncomfortable questions about whether prosperity inevitably breeds inequality.

Figure 1: Net wealth inequality and wealth share by wealth percentile, Member States, 2021

Countries are ranked from lowest to highest level of wealth inequality (data for Poland refers to 2017 instead of 2021) as measured by the Gini index, which ranges from values of 0 (maximum equality) to 100 (maximum inequality). The bars show the wealth shares of certain percentiles of the wealth distribution. For example, the red sections show the wealth shares of the bottom 50% of the population in the total net wealth of the country.

Source: HFCS 2021 (2017 for Poland)

Divergent Trajectories

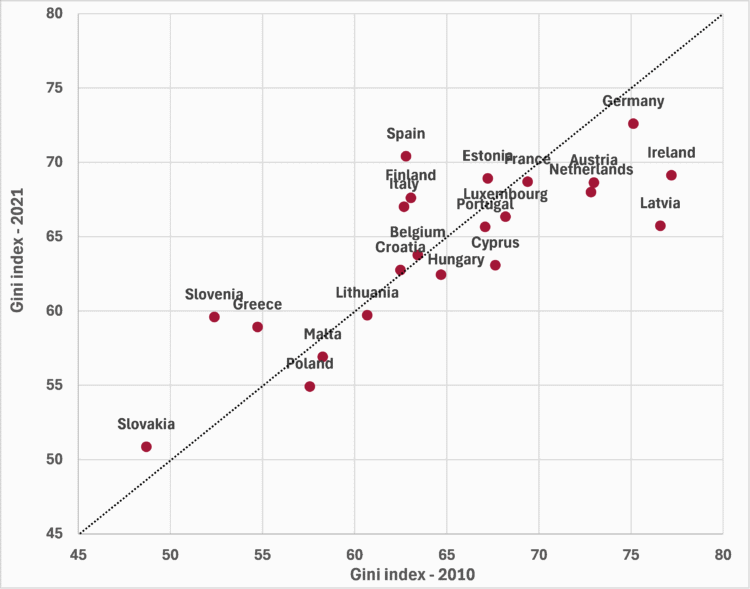

The evolution of wealth inequality between 2010 and 2021 defies simple narratives. Inequality increased in nine countries whilst declining in thirteen, painting a complex picture of shifting fortunes across the continent. Spain, Finland and Estonia experienced significant, sustained increases throughout the period. Slovenia and Italy, meanwhile, saw sudden sharp spikes that transformed their inequality landscapes in a short period of time.

Among nations where inequality declined, the trend often reflected sustained improvement. Latvia, Ireland, Austria, Germany and Luxembourg — several starting among Europe’s most unequal — witnessed consistent reductions. This pattern suggests tentative convergence, as highly unequal countries saw disparities narrow whilst some egalitarian nations, including Slovenia, Greece and Slovakia, experienced growing gaps.

This convergence offers no grounds for complacency. Rather, it highlights wealth distribution’s dynamic and unpredictable nature, suggesting that neither equality nor inequality represents a stable equilibrium. Policy choices and economic shocks can rapidly reshape distributional outcomes, for better or worse.

Figure 2: Net wealth inequality, EU Member States, 2010 and 2021 (Gini index)

Years other than 2010 and/or 2021 are used in some countries due to data unavailability (2014 instead of 2010 in Estonia, Hungary, Ireland, Latvia and Poland; 2017 instead of 2010 in Croatia and Lithuania; 2017 instead of 2021 in Poland). The black line represents the 45° line of equal proportionality.

Source: HFCS 2010 and 2021

Housing: The Great Divider?

Housing emerges as inequality’s primary engine, accounting for 63 per cent of total net wealth across the EU in 2021. Disparities in home ownership rates and property values therefore explain the lion’s share of wealth inequality. Critically, countries experiencing the sharpest inequality increases — Slovenia, Spain and Greece — saw housing wealth disparities drive the change.

Yet housing plays a paradoxical role in wealth distribution. Whilst driving inequality, home ownership simultaneously buffers against economic insecurity and can moderate overall disparities. Housing wealth typically displays less concentration than financial assets, and nations with high home ownership rates generally exhibit lower wealth inequality. Among the six countries with the highest ownership rates — all newer member states — five rank among Europe’s most equal. Conversely, four western European nations with the lowest home ownership rates — Germany, Austria, France and the Netherlands — are among the most unequal.

This relationship suggests home ownership’s democratising potential, distributing wealth more broadly than financial markets ever could. Yet this potential increasingly eludes younger Europeans, for whom home ownership represents an ever-receding dream. As property prices and rents surge beyond income growth, entire generations find themselves locked out of wealth accumulation’s primary vehicle. This exclusion delays life transitions, undermines financial security and entrenches intergenerational inequality in ways that will reverberate for decades.

Charting a Path Forward

Addressing Europe’s wealth divide demands comprehensive action centred on housing affordability. Immediate measures should include targeted subsidies for low-income renters, aggressive expansion of social housing stock, and meaningful incentives for affordable home construction. These interventions could begin reversing the exclusionary dynamics currently reshaping European society.

Beyond housing, broader strategies must address wealth concentration’s root causes. Progressive wealth taxation, coupled with comprehensive wealth declarations, could generate resources whilst improving transparency. Financial literacy programmes would empower citizens to build assets more effectively. Most crucially, policy packages must explicitly target middle-class and low-income groups, ensuring that prosperity’s benefits flow beyond narrow elites.

The stakes could hardly be higher. Extreme wealth concentration threatens not merely economic efficiency but democracy itself, as concentrated wealth translates into concentrated power. Only through sustained, coordinated action can Europe begin dismantling the profound disparities now shaping its trajectory. The alternative—accepting permanent division between wealth’s possessors and those excluded from its benefits—represents a future no democratic society should tolerate.

Carlos Vacas-Soriano is a research manager in the employment unit at Eurofound. He works on wage and income inequalities, minimum wages, low pay, temporary employment and employment quality.