After years of being sidelined in the European policy debate as labour markets recovered in the wake of the Great Recession, inequality is back on the agenda following the COVID-19 pandemic and the ensuing cost-of-living crisis. A widespread public perception is that income inequality is growing while the middle class is shrinking. However, the reality is more nuanced, as shown by a recently published Eurofound report.

Income convergence reduces EU-wide income inequality

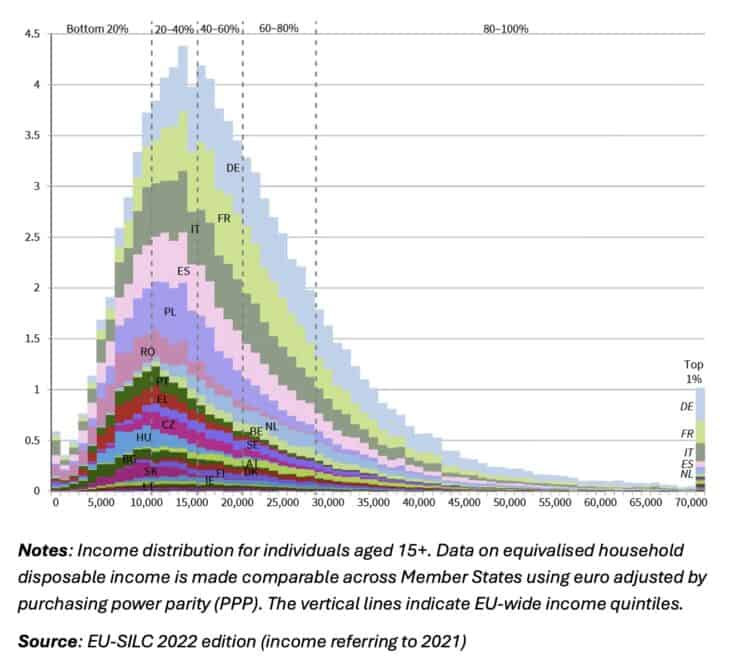

Empirical studies that adopt a truly EU-wide approach to measure income inequality are scarce. Doing so requires all EU citizens to be considered part of a single EU-wide income distribution (shown in Figure 1) shaped by income disparities between and within countries. Two insights emerge from this exercise. The first is that income disparities between countries are reflected in the different positions they occupy on the EU-wide income distribution: the populations of the Member States that joined the EU after the 2004 enlargement (the EU13) are relatively more present in the bottom EU-wide income quintile, while those of the pre-2004 Member States (the EU14) account for almost all the top quintile. (Most of the top 1 per cent of income earners come from Germany, France and Italy, followed by Spain and the Netherlands.)

The second insight is that income disparities within countries are evidenced by the fact that countries, especially the largest ones, are spread over the EU-wide income distribution and are relatively present across all the income quintiles.

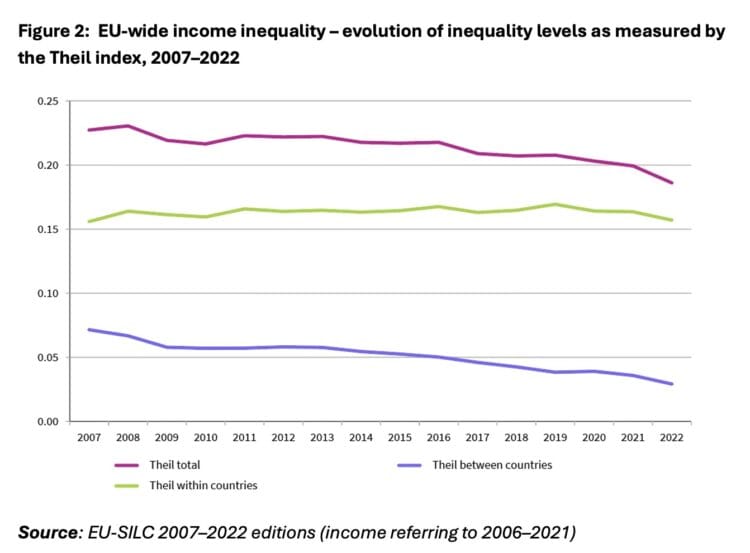

Income inequality in the EU as a whole can be broken into two elements using the Theil index: between-country and within-country income disparities (see Figure 2). The index shows that EU-wide inequality declined over the period. This reversed temporarily during the Great Recession and its aftermath before resuming thereafter and continuing even in the most recent years of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The contribution of between-country and within-country income disparities is very different. Income disparities between countries are reduced, and this is entirely responsible for the fall in EU-wide income inequality over the 15 years analysed. This was caused by strong convergence in average income levels between Member States, largely due to remarkable catch-up income growth in most of the EU13 and much more modest progress in the EU14.

On the other hand, within-country income disparities represent the lion’s share of EU-wide income inequality (and increasingly so, given the abovementioned reduction in income disparities between countries). Still, they did not play a significant role in the evolution of EU-wide income inequality because they were broadly similar at the beginning and the end of the period.

Mixed picture within EU27 countries

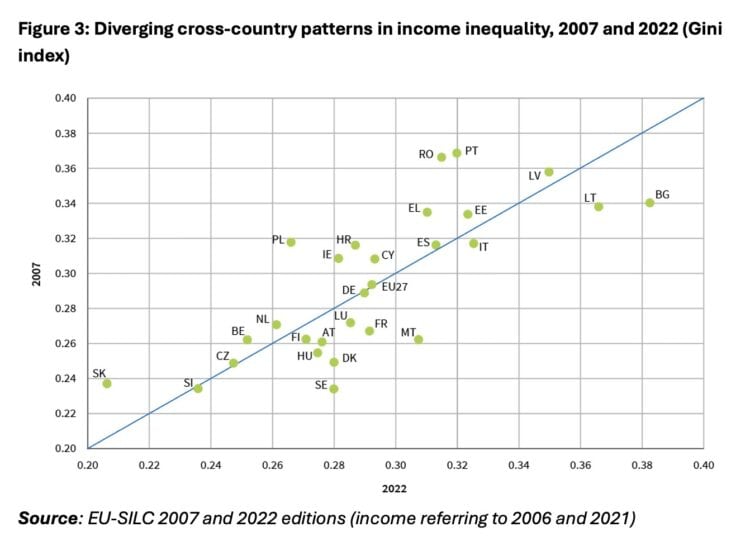

The relative stability of aggregate within-country income inequality conceals diverging patterns across countries, captured by comparing inequality levels at the beginning and the end of the period (Figure 3). The picture is mixed: inequality increased in around half of the Member States (the 13 countries below the diagonal line in Figure 3), especially in Sweden, Denmark, Malta and Bulgaria; and inequality declined in the other half (the 14 countries above the diagonal line), significantly so in Poland, Romania, Portugal and Slovakia.

Some convergence in income inequality levels between countries took place. Among the countries initially characterised by relatively low inequality, a consistent upward trend is apparent in several of the EU14, including the Nordic Member States (Sweden, Denmark and Finland) and some continental Member States (Austria, Luxembourg and France), as well as Malta and Hungary.

Among those countries initially characterised by relatively high inequality levels, a moderation occurred in several of the EU13 (Romania, Poland, Croatia, Latvia, Estonia and Cyprus), as well as Portugal, Greece and Ireland. These diverging trends have shaken up the position of some countries along the inequality scale: Sweden and Denmark have become relatively more unequal, while Poland is much more equal now than in 2006.

Middle class contraction

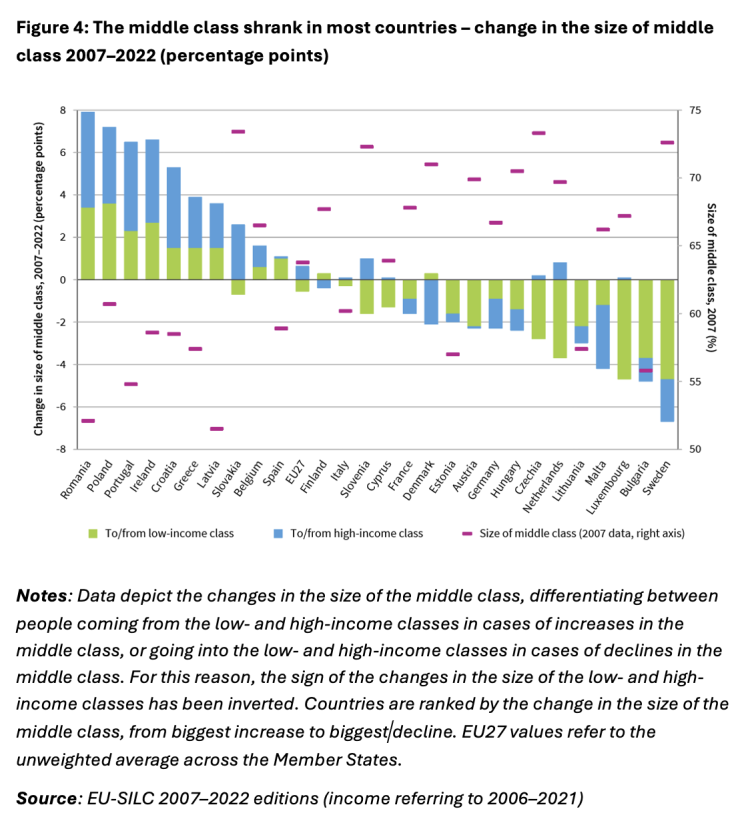

EU Member States are middle-class societies, with most people belonging to this class (middle class is here defined as people with an equivalised household disposable income between 75 per cent and 200 per cent of the national median.) On average, across the Member States, the middle class comprises 64 per cent of the population (while 28.5 per cent and 7.5 per cent belong to the lower-income and higher-income classes, respectively), ranging from above 75 per cent in Slovakia to 51 per cent in Bulgaria. A large middle class makes for cohesive societies where many people are concentrated around the middle of the income distribution. This explains why the size of the middle class and income inequality levels are closely correlated.

Changes in the middle class’s size and income inequality are closely correlated, too, but the picture across the Member States is more generalised in this case. While the cross-country average size of the middle class has remained broadly stable over the period (contracting negligibly from 64 per cent to 63.8 per cent), it shrank in almost two-thirds of Member States, although to varying degrees. This is shown in Figure 4, where countries are ranked from the most significant increase in size to that with the largest decline. The contraction was more significant in those countries to the right of the figure, a mix of EU14 (especially Sweden and Luxembourg, and also the Netherlands, Germany, Austria and Denmark) and EU13 (especially Bulgaria and Malta, and also Lithuania, Czechia, Hungary and Estonia). Conversely, the middle class expanded in 10 countries (to the left of the figure), very significantly in some of the EU13 (Romania, Poland and Croatia), Portugal and Ireland.

Figure 4 offers two more insights. One, the generalised shrinking of the middle class translated to a greater extent into downward movements of people into the lower-income class. Two, countries have converged in terms of the size of the middle class, due to its contraction in some countries where it was very large initially (for instance, Sweden, Denmark, the Netherlands and Czechia) and its expansion in others where it used to be smaller (for instance, Romania, Latvia and Portugal).

An analysis of the composition of the middle class shows that people with lower educational levels, younger people, women, people living in single-adult households and unemployed people are less likely to be part of the middle class (and much more likely to belong to the lower-income class). Moreover, it has become increasingly difficult over time for people who have low educational attainment, are young or are unemployed to enter the middle class.

Forces shaping the trends

One factor that has pushed income inequality higher over the period (and reduced the middle class) is the weakening of the income redistribution carried out at the family level (mainly due to a fall in average household size), which has occurred in most countries. Another is the widening of wage disparities in labour markets, which has occurred in around half of countries.

On the other hand, two factors that have tended to lower income inequality (and increase the middle class) are the higher employment and activity rates in most countries and the income redistribution carried out by the welfare state in more than half of countries.

The latter was especially evident during the COVID-19 pandemic, when the welfare states of most countries deployed job retention schemes, which prevented a squeeze on household incomes. As a result, the impact of the pandemic was much more moderate than that of the Great Recession between 2008 and 2013: employment levels fell modestly and in fewer countries, which explains why income levels continued expanding (albeit more moderately), and rises in income inequality across countries were less significant.

Better policy design

Nevertheless, the weakening of the welfare state has been a factor in growing income inequality in some Member States. The available data show that the poorest people find it especially difficult to access the social benefits to alleviate their situation, which points to the need to improve the accessibility of benefits and to close the gaps in application processes.

Moreover, only a third of Member States allocate social benefits in a progressive way (meaning those in the bottom half of the income distribution receive a larger share of the benefits than those in the top half). Even when pensions are excluded, there are several countries where higher-income earners receive a larger share of the benefits than their lower-income counterparts. Greater income redistribution would improve the welfare state’s capacity to cushion income inequality and make benefit allocation more progressive.

Different patterns across EU regions

EU-wide income inequality has declined over the past 15 years due to strong income convergence between the Member States. This is largely due to the remarkable catch-up in household income growth in the EU13. Income inequality increased in around half of the Member States, while the middle class shrank in almost two-thirds of them, although to varying degrees. When these findings are combined, a nuanced picture of different patterns across European regions emerges. The most positive aspect is presented by many of the EU13: apart from strong income growth in most, several countries became less unequal, and their middle class expanded (Romania, Poland, Croatia, Slovakia and Latvia). A bleaker dynamic characterises the EU14. Many registered growing inequality and a shrinking middle class: all three Nordic Member States (Denmark, Finland and Sweden) and Austria, Germany, France and Luxembourg among the continental Member States. In the Mediterranean Member States (Greece, Italy, Portugal and Spain), this did not occur (except in Italy). Still, disparities narrowed against a background of poor income growth, which prevented a significant convergence of these countries towards higher income levels.

Read the full research report: Developments in income inequality and the middle class in the EU

Carlos Vacas-Soriano is a research manager in the employment unit at Eurofound. He works on wage and income inequalities, minimum wages, low pay, temporary employment and employment quality.