More than a year into a global pandemic which has turned the status quo on its head, there is recognition around the world that the recovery process should focus on moving forward rather than a return to ‘business as usual’. The twin public-health and economic crises stemming from the pandemic have highlighted and exacerbated inequalities in our societies and revealed the shortcomings in how our economies are run.

At the same time, climate change, biodiversity loss and political polarisation within the European Union pose additional challenges to our social and economic systems. As the EU attempts to address these new challenges, the scale of member states’ collective response must be measured against the potential for rapid and large-scale transformation.

The €672.5 billion Recovery and Resilience Facility (RRF) is a once-in-a-generation opportunity for member states—not only to tackle the public-health crisis but also to pursue the transition to a low-carbon, resource-light economy, restore nature and biodiversity and create high social welfare and cohesion.

To make a real, enduring difference, for the planet and the people who inhabit it, member states must look beyond solving the short-term problems of today to design policies and measures which create systemic change for sustainable and resilient societies, able to adapt to or mitigate future crises. And while these solutions need to benefit people and economies, they must also protect nature and biodiversity, as climate change and biodiversity loss are threatening the essential foundations of life.

Unique analysis

To receive funding from the RRF, member states were required to submit their own National Recovery and Resilience Plans (NRRPs) to the European Commission. ZOE Institute, in cooperation with the New Economics Foundation, developed a Recovery Index for Transformative Change (RITC), to assess the adequacy of these plans to contribute to the necessary transformation of society.

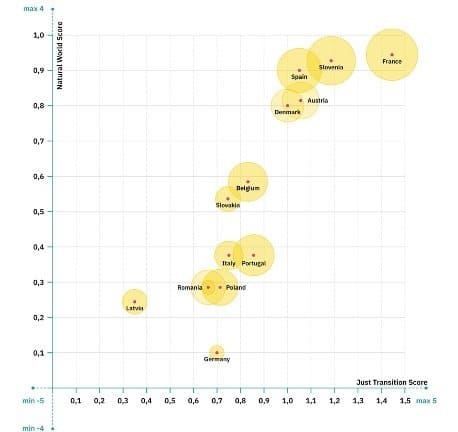

Using the index, ZOE Institute assessed 13 NRRPs (see figure), evaluating the potential of—and risks associated with—the investments and reforms envisaged, against the criteria of a natural world, a just transition and systemic change. This analysis is unique as it not only explores where the money is going but also how it is to be invested. We examined specifically whether the investments would enable a fundamental shift towards a regenerative, distributive and resilient economy, rather than consolidating the status quo.

It’s clear from this analysis that member states are largely missing the opportunity to connect new reforms with investments to lead Europe towards a climate-neutral and socially-balanced future. Much more should be made of the recovery to build an economy that protects the climate and delivers social justice.

Scores of member states on the RITC

Do no harm

A cornerstone of our analysis has been an assessment of the application of the ‘do no significant harm’ (DNSH) principle, adopted by the commission to ensure member states evaluated the environmental impact of all measures included in the NRRPs. This represents a significant step forward in the decades-long work to integrate environmental impacts into economic and social policy in pursuit of coherence on sustainable development. Utilised well, it is an essential tool for realising climate and biodiversity objectives.

In most cases, however, member states missed this opportunity and did not apply the DNSH principle in a rigorous way—often overlooking the risks to biodiversity in particular. For example, the Portuguese plan foresees an expansion of the road network, which entails direct emissions not only from combustion engines but also from tyres, brakes and the road surface, while the resulting damage to biodiversity is not sufficiently taken into account.

There are three important blind spots across the plans’ DNSH assessments: the impact of infrastructure projects on biodiversity and nature, the increased energy consumption the digital transition will create and the need to embed measures related to material use into a circular economy. For example, within the widespread investments envisaged for the purchase of new digital equipment for education and public administration, reuse and appropriate procurement policies are lacking.

Social cohesion

Social cohesion needs also to be prioritised as part of an overarching vision for the future. The nature of the recovery will depend on whether the investments and reforms made today support the green and just transition Europe needs to realise. Despite far-reaching efforts, there remain gaps between the ambition and what is planned by member states.

Protecting biodiversity, while recognising its essential role in the economy, and building local resilience, by addressing economic disparities in a targeted way, are two key weak points of the plans. Particularly concerning is that most lack explicit consideration of the regions and people left behind by the combined impact of digitalisation and globalisation.

A recent report from Vivid Economics shows that nature-based solutions offer a unique avenue to deliver environmental, social and economic objectives together. Yet, this is largely absent from the NRRPs, with only 1 per cent of funding going towards such measures.

Not enough

The funding from the RRF comes at a crucial time, but it is not enough to reach our critical aims: to deliver systemic transformation, to limit global heating to 1.5C, to realise a just transition or to achieve the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals. An estimated €349 billion to €883 billion in additional investments is needed annually just to realise the climate and environmental targets set by the commission.

The commission itself estimated a yearly investment need of €470 billion in the context of the old 2030 climate and environmental targets, which included a CO2-emissions reduction of 45 per cent (now 55). Other consultancies and researchers have come to similar conclusions.

With the NRRPs, however, only 37 per cent of the €672.5 billion over two and a half years is required to be invested in the green economy, amounting to roughly €100 billion yearly. Nor does this include measures essential for realising a just transition. It is clear this level of investment is insufficient for a systemic transformation of our societies and economies.

Building a future Europe

A crucial stepping-stone is to reframe the RRF investment as a foundation for building the future of Europe. The EU and member states can learn from the progress achieved, for example by applying the DNSH assessment to all future public investment. A multi-criteria analysis, using the DNSH principle, which connected social issues to environmental and social sustainability more deeply, could have a very strong and positive impact. Any future investment mechanisms need to be scrutinised in such a rigorous way.

Operationalisation and implementation of the plans is also critical: the devil is in the details. Many measures can be carried out in ways that either increase negative side-effects or increase policy coherence and co-benefits—it is essential that member states achieve the latter. Their monitoring and evaluation frameworks and the scrutiny of the commission must adopt a systemic perspective, which takes into consideration the interconnections among policy areas. A transformation to sustainable prosperity cannot wait until after the recovery. It must start with it, run parallel to it, and go deeper to address the roots of the challenges we face.