The central idea of the Commission’s Clean Industrial Deal initiative, announced under its strategic policy guidelines for the next policy cycle, is ‘clean technology competitiveness’. This is also the backbone of Mario Draghi’s report on the future of European competitiveness.

The report identifies opportunities for sustainable growth in Europe based on the EU’s position as a world leader in clean technologies, including electromobility. The report contends that, besides closing the innovation gap with the US and increasing security while reducing dependencies on China for raw materials and technology, all member states must have a joint plan for decarbonisation and competitiveness in the EU.

The first test case of the concept is linked to the Commission’s proposal to impose definitive countervailing duties on imports of Battery Electric Vehicles (BEVs) from China following the anti-subsidy probe launched in 2023. The Commission’s recommendation for duties ranging between 8 per cent and 35 per cent on made-in-China BEVs (on top of the already existing 10 per cent) was approved by the European Council in October 2024 and is expected to take effect from this month.

Regarding recent market developments in BEV sales, according to the European Automobile Manufacturers’ Association (ACEA), the four-year continuous and, at times, accelerating growth trend of BEV sales was broken in spring 2024, with four consecutive double-digit declines since April. August 2024 saw the most significant drop across the EU at 43.5 per cent, led by Germany, which registered a dramatic 68.8 per cent fall in the wake of the 2023 phase-out of BEV purchase subsidies.

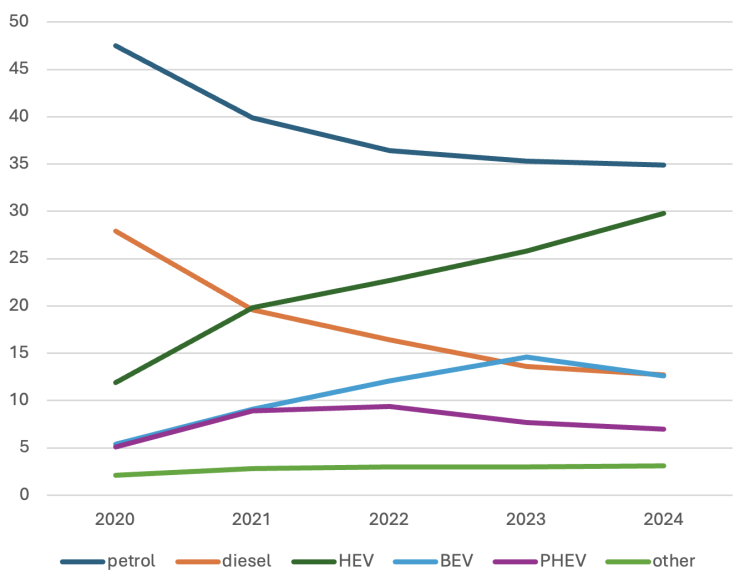

Figure 1 shows the distribution of new car sales by fuel type in the EU27 since 2020. The share of petrol and diesel car sales continued to decline, although it flattened out in the last period, reaching 34.9 per cent and 12.7 per cent, respectively, for the first eight months of 2024. The share of Hybrid-Electric Vehicles (HEVs) grew further, reaching nearly 30 per cent, while that of Plug-in Hybrids (PHEVs) remained flat at 7 per cent. Most importantly, the share of full-electric BEVs, which grew continuously until the end of 2023 with a 14.7 per cent share in new car sales, began to fall in 2024, down to 12.7 per cent for the first eight months of the year. These trends illustrate that the momentum in the shift towards electromobility has been broken in 2024.

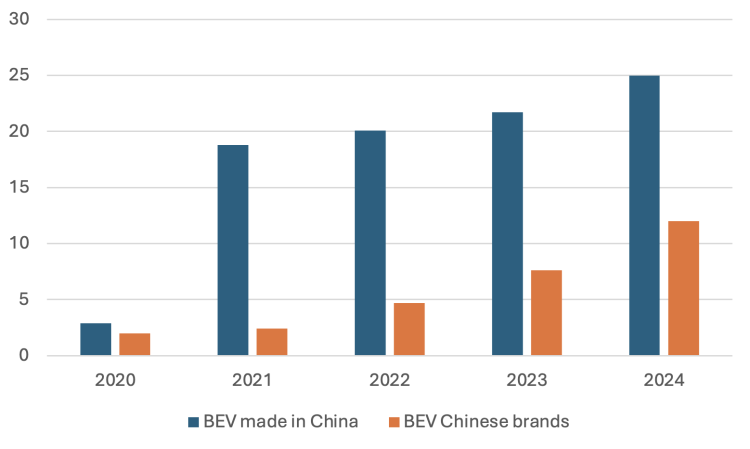

A further concern in Europe, linked to the discussion on industrial policy, is that China’s share in the European electric car market is rapidly increasing. Figure 2 shows the share of BEVs made in China in total EU BEV sales between 2020 and 2023. BEVs made in China include Western brands like Tesla, Dacia, and Mini, which are manufactured there and exported to Europe, as well as Chinese brands like BYD, MG, and Polestar. While in 2020, 2.9 per cent of BEVs sold in Europe were made in China (2 per cent being Chinese brands), in 2023, they accounted for 21.7 per cent (7.6 per cent Chinese brands). A recent projection by the NGO Transport & Environment (included in the graph) estimates that by 2024, all made-in-China BEVs will reach a quarter of EU27 BEV sales, while Chinese brands alone will account for 12 per cent.

This trend also results from European car makers focusing their business strategies on premium market segments, neglecting the production of smaller, more affordable entry-level electric cars. If the European automotive industry cannot produce affordable clean cars, this will not only exacerbate inequality in clean mobility but also pose a threat to high-quality jobs in European automotive manufacturing.

Based on European Trade Union Institute (ETUI) research led by myself and Tomasso Pardi, we have already warned about this threat; unfortunately, developments in 2024 indicate that this was not a hypothetical scenario. The announcement by Audi management to cease the production of its top-of-the-range electric car, the Q8 e-tron SUV, at its Brussels plant puts the future of the entire plant, which employs 3,000 skilled workers, at risk. Simultaneously, Volkswagen continues to struggle with the transition to electromobility. In an unprecedented move, in early September 2024, management announced consideration of two plant closures in Germany, abandoning an employment guarantee under its Pact for Future, which was seen as a co-determination model and responsible just transition practice. It is scrapping two crucial model launches: one that was viewed (compact EV SUV) as the saviour of Wolfsburg and the Trinity model in East Germany’s Zwickau (regarded as a pioneering model with advanced autonomous driving functions).

Past success (in combustion engine technology) offers no template for the future. Based on ongoing research at the ETUI, we have also emphasised that electromobility (with its lower labour demand) poses a lesser threat to EU jobs. The most critical issue is how EU manufacturers can keep pace with delivering clean mobility solutions. In line with the priorities of the EU’s new policy cycle, this is indeed about redefining the competitiveness of a pivotal industrial sector in the new era of electromobility.

Now that the EU has announced protective countervailing duties on BEVs from China, the big question is whether and how the EU automotive industry will benefit from this protective measure. Continuing the old business model of upmarketisation by building ever bigger, heavier and more expensive cars (even if often under hybrid or plug-in hybrid cover) would be a significant failure. Doing this under the protective umbrella of tariffs would also not serve consumers or social justice and would threaten the achievement of road-transport emissions targets. Without imports from China, it will be harder to reach these targets, but abandoning already binding legislative commitments, such as the 2035 exit from the combustion engine, would be the worst option. This is not only due to climate considerations but also for the mid- and long-term future of European automotive jobs.

The sector is on the verge of a crisis, as the cases of Audi Brussels and Volkswagen demonstrate. Tariffs on electric cars from China will not solve their problems; the industry needs to reinvent itself once again. After the Diesel scandal, it has already taken a bold step, but it remains to be seen if this is bold enough. The sector will serve as a test case for the EU’s industrial policy awakening in the new political cycle. It will also function as a laboratory for just transition policies and practices, as it is clear that the sector will require a dedicated just transition strategy with proper funding at the EU level.

Béla Galgóczi is Senior Researcher at the European Trade Union Institute and editor of Response measures to the energy crisis: policy targeting and climate trade-offs (ETUI, 2023).