The latest European Social Survey shows rising concern about climate change. But is it enough?

The European Social Survey (ESS) is an academically driven survey which has been conducted across Europe every two years since 2002. It was developed to offer academics a reliable comparative dataset, covering the general population across much of Europe and measuring long-term trends.

The questionnaire includes almost 200 questions on topics such as crime and justice, democracy, discrimination, Europe, government, health and wellbeing, identity, immigration, media, political values and participation, religion and institutional and social trust. The data, collected from respondents and weighted to be representative of the national population of each country, can be analysed against a range of demographic social categories.

Additionally, in each round of the ESS, two topics are covered in more depth, following a call for proposals. During round eight (2016-17), this led to the inclusion of around 30 questions on climate change and energy—initially proposed by a team of climate researchers led by Wouter Poortinga (Cardiff University).

Three of these questions were also asked in round ten (2020-22). Due to measures implemented to prevent the spread of the coronavirus, the fieldwork period for this latest iteration of the survey was extended. This means that we currently have data from ten countries, collected via in-person interviews. Seven of these also participated in round ten, and we can already see some interesting trends in responses collected four to six years apart.

Majority worried

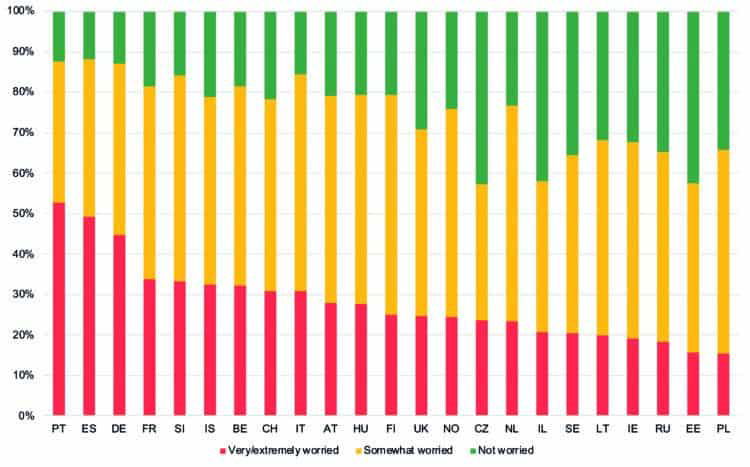

The 2016-17 round of our survey already indicated concern about climate change. In all 23 countries involved, a majority of respondents indicated that they were ‘somewhat’, ‘very’ or ‘extremely’ worried about it. In aggregate, those ‘worried’ ranged from a high of almost 90 per cent in Spain to a low of around 60 per cent in Czechia, Estonia and Israel.

In places such as Portugal and Spain, where higher temperatures caused by climate change may appear even more pronounced, around half of respondents were very or extremely worried. This compared with only 15 per cent in Estonia and Poland (Figure 1).

Figure 1: ‘How worried are you about climate change?’ (%, 2016-17)

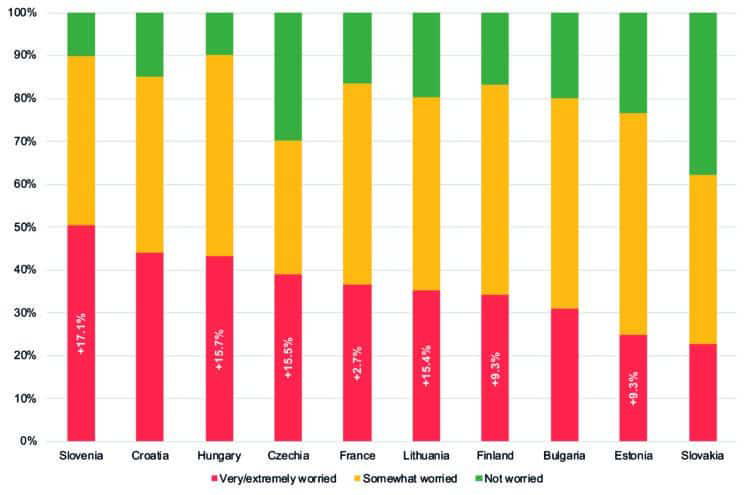

The proportion of those who were very or extremely worried in 2016-17 increased in all seven countries where the 2020-22 data are currently available. There was a particularly large increase in several: by 17 percentage points in Slovenia, 16 in Hungary and Czechia, 15 in Lithuania and almost ten in Estonia and Finland.

In absolute terms, in all ten countries where round-ten data are available, at least two-thirds of respondents are somewhat, very or extremely worried about climate change. This ranges from slightly more than 60 per cent in Slovakia to 90 per cent in Hungary and Slovenia (Figure 2).

Only in Portugal, however, are over 50 per cent of respondents very or extremely worried. This underlines that there are still many people in Europe who would not yet see a ‘climate emergency’—climate scientists and environmentalists still have some way to go to convince them.

Figure 2: ‘How worried are you about climate change?’ (%, 2020-22)

Personal responsibility

We also asked respondents whether they felt a personal responsibility to reduce climate change. Answers were given on an 11-point scale, from zero (none at all) to ten (a great deal). We plotted the mean national score for all respondents in both rounds (Figure 3).

Figure 3: perceived personal responsibility to reduce climate change (mean, 2016-17 and 2020-22)

In the seven countries where data are available for both rounds, we see an increase in the overall national level of adduced personal responsibility. This is again a significant increase in many places—by over one point in Hungary (1.5), Estonia (1.2) and Lithuania (1.2), and one point exactly in Czechia and Slovenia. In France and Finland—where we saw higher mean scores in 2016-17—there were a small and a non-significant increase respectively (0.6 and 0.3 points) by 2020-22.

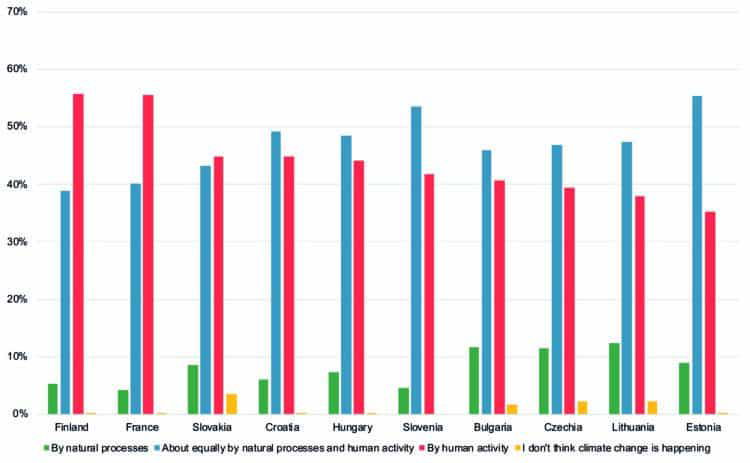

Causes of climate change

We also asked respondents in both rounds whether they thought climate change was caused by natural processes, human activity or both. Overall, a majority of respondents in the ten countries where round-ten data are available believe that climate change is caused by human activity or about equally by natural processes and human activity (Figure 4).

Figure 4: climate change caused by natural processes, human activity or both (%, 2020-22)

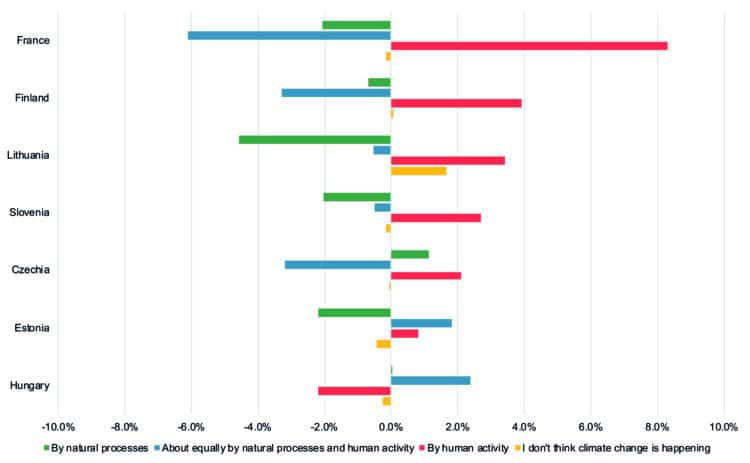

In six of the seven countries where data are available over time, we found an increase in the proportion of respondents who think that climate change is caused by human activity. This increased ranged from over eight percentage points in France to barely any change in Estonia.

In five of these countries, there was a reduction in the proportion of respondents who felt that climate change was caused by natural processes in round ten, compared with round eight. Only in Hungary did we find a reduction in the proportion of respondents who felt that climate change was caused by human activity (Figure 5).

Figure 5: changes in proportions of respondents allocating causes of climate change to natural processes and human activity, 2016-17 to 2020-22 (percentage points)

Growing consensus

With the most recent ESS data (2020-22) now available for ten countries, including seven where data are comparable to 2016-17, some preliminary conclusions can be drawn. It appears that concern about climate change has increased over time and that respondents now feel more personal responsibility to try to reduce it.

There seems also to be a growing consensus that climate change is caused by human activity. In only one of these ten countries, however, do most people say they are very or extremely worried about it.

Our next data release, in late November, will add 15 countries, facilitating a fuller picture. This will enable us to see whether the growing concern about climate change and increasing willingness to take personal responsibility are replicated elsewhere.

All data analysis included in this article was undertaken with design weights only; post-stratification weights will be applied in later analysis. All ESS data are freely available for non-commercial use

Prof Rory Fitzgerald became director of the European Social Survey European Research Infrastructure (ESS ERIC) in 2013, having been a senior research fellow working on the project at the City University of London from 2004. He is an associate editor of the journal Survey Research Methods.