When the pandemic hit the European Union its economy had decelerated somewhat but unemployment had reached its lowest level for years, while inflation remained stubbornly below its 2 per cent target. Inequality had decreased, too. All these achievements were however disrupted by an enormous economic shock as the economies of the member states went into lockdown.

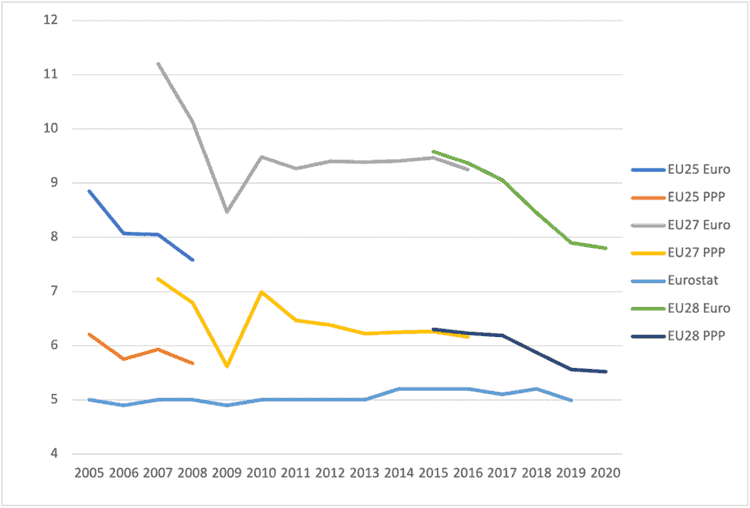

In 2019, EU-wide inequality had reached its lowest level since the 2007 eastern enlargement (Figure 1). After many years of stagnation, in 2016 income disparities had eventually started to decline.

The impact of the pandemic is difficult to assess, due to the lack of recent household-survey data. Ignoring possible changes in the distribution of disposable income within countries in 2020—available evidence is ambiguous at best—we base our calculations of EU-wide inequality in that year on known disparities of growth among member states. Our estimate (published by the Friedrich Ebert Foundation) shows that the pandemic strongly slowed the previous decline in inequality but did not reverse it.

Quintile ratio

To gain a realistic estimate of EU-wide inequality, we use EU-SILC household-survey data from Eurostat (latest available year 2019) to combine within- and between-country inequality. We measure the quintile ratio (S80/S20), dividing the income of the richest fifth of the population by that of the poorest. The resulting 2019 pre-crisis value of EU-wide inequality is the lowest since 2008, with a value of 7.9 for the quintile ratio at exchange rates and 5.56 at purchasing-power parities.

Figure 1 presents that ratio since 2005 at exchange rates and PPP. The lowest curve, oscillating around five, is the official Eurostat value for the whole EU. It is much lower and more stable than our values because it neglects the income disparities among countries. It just gives the average, weighted by population, of the national values of the quintile ratio.

Figure 1: EU-wide inequality (S80/S20 indicator), 2005-20

EU-wide inequality declined between 2005 and 2009. The apparent jump in 2007 was caused by the inclusion of Romania and Bulgaria, two poor and large countries which joined the EU that year. In 2009, the financial crisis and the Great Recession hit the EU and caused inequality to increase substantially, which bodes ill for the current crisis.

That rise was partially reversed in 2011. Afterwards, the EU entered a phase when inequality changed little. In 2017, inequality eventually resumed its decline, reaching a new all-time low (for the EU-27+) in 2019.

The evolution of EU-wide inequality is driven mostly by the higher growth of poorer member states, in particular in central and eastern Europe. Their nominal gross domestic product grew by 51 per cent between 2008 and 2019, while that of the richer member states in the north-west increased by just 20 per cent. These structural features need to be taken into account when we analyse the impact of the pandemic.

Hard to guess

The case of Germany shows the ambiguities involved in so doing. The pandemic and the associated lockdowns hit people working in personal services who could not work from home harder than those in better-paid administrative or management jobs. There are also clear indications that inequality of wealth has grown as asset prices have strongly increased in the wake of loose monetary policies. On the one hand, additional wealth should translate into higher capital incomes in the medium term (as when rents increase). On the other hand, zero or negative interest rates reduce income from savings. The resulting total effect on the income of the richer, asset-owning strata remains hard to guess.

It seems quite likely that the distribution of market income worsened in 2020. But we want to estimate disposable income: inequality of disposable income is usually much lower because redistribution through the tax and welfare systems shifts income from the richer strata to the poorer. During the pandemic, all countries have adopted measures to protect jobs and income.

In the end, it is likely that disposable income did not change a lot. The case of Germany, where different studies deliver mixed results (DIW, WSI, ifo, IdW) seems to confirm that ambiguous finding. Whether that is true for other member states with less generous income support during the pandemic remains open.

Different degrees

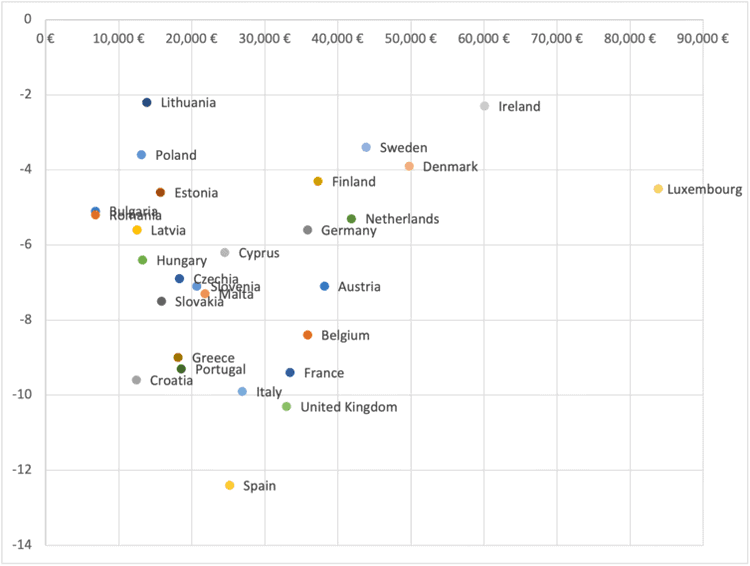

Whatever these uncertainties regarding within-country inequality in 2020, between-country distribution of income is much clearer, as the estimates of GDP growth are already pretty reliable. The pandemic has affected the member states to different degrees. Countries depending on tourism suffered more than those relying on manufacturing. Less indebted member states, such as Germany, could afford stronger fiscal-support programmes than already highly-indebted countries.

These qualities, however, are not closely correlated with per capita income before the crisis. As Figure 2 shows, the dispersion within both income brackets is very high, although the richest member states have tended to have shallower recessions.

Figure 2: decline of GDP in 2020 (%) in relation to per capita income

Due to the data deficiencies and uncertainties, we calculate our estimate of EU-wide inequality for 2020 exclusively on the basis of the reported changes in between-country inequality. Using this method, we obtain the following estimates: inequality measured by the quintile ratio declined slightly (in comparison with 2019), with the estimated values for 2020 (Figure 1) 5.52 at PPP (5.56 in 2019) and 7.78 at exchange rates (7.9 in 2019).

The impact of the pandemic on EU-wide inequality thus appears to be weak. The ensuing recession has slowed down the recent declining trend but not reversed it as the financial crisis did in 2009-10. Given the uncertainties, this assessment must be considered provisional, as it neglects the development of inequality within countries. On that the final judgement will be available from Eurostat in the autumn.