The pandemic, which has been going on for almost two years, has brought about many changes in the world of work. These include the undoing of limits on working hours, increased control and interference in the private sphere and more stress for what have become fragmented workforces. The effects will be enduringly felt—some observers speak of a ‘new normal’ of future work.

This year’s iteration of the DGB Good Work Index, published by the German trade union confederation, explored the consequences of the pandemic for workers in the country via a survey of 6,400 randomly selected employees. This ran from January to June 2021, a phase characterised by high infection. The survey results show how extensively working conditions have changed in the past one and a half years—particularly in the digitalisation of work and the growth of working from home.

Strong driver for digital work

Workplace infection control should ensure that personal contacts are reduced, minimum distances observed, personal-protection measures and hygiene rules followed and, where possible, face-to-face meetings replaced by digital communication. The pandemic was therefore a strong driver for digitalisation.

Almost half of all respondents (46 per cent) reported that new software was used in their work during the pandemic. The vast majority (75 per cent) said the application(s) had been acquired because of it.

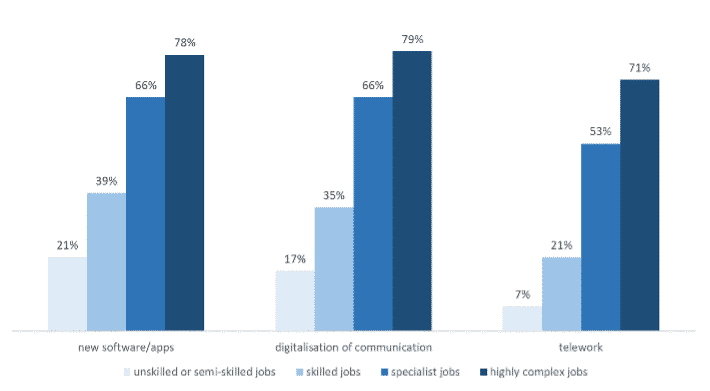

The extent of digitalisation however varies greatly among different groups of employees (see chart). One in five employees (21 per cent) in unskilled or semi-skilled jobs found themselves working with new software. But at the highest qualification level—‘highly complex jobs’, for which a university degree is usually required—the work of almost four out of five employees (78 per cent) was digitalised in this way.

Digitalisation and telework according to occupational skill levels

New digital work tools were often used to enable working ‘at a distance’. How consistently this was implemented was also strongly related to the requirements of the job.

Seventeen per cent of employees in unskilled and semi-skilled jobs reported that they had switched from face-to-face to digital communication with colleagues and superiors. In the case of ‘highly complex jobs’, the figure was 79 per cent.

‘Telework obligation’

The Corona Occupational Health and Safety Ordinance of January 2021 in Germany introduced a kind of ‘telework obligation’. Employers had to offer their employees the opportunity to carry out their work from home ‘if there are no compelling operational reasons to the contrary’. As a result, working from home increased sharply.

Almost one third of respondents (31 per cent) have worked from home (very) often since the beginning of the pandemic. More than half of this group (54 per cent) had not done so before.

Not surprisingly, the possibility of working from home shows clear correlations with occupation. While, for example, 94 per cent of teachers (very) frequently worked from home, the figure was 1 per cent for geriatric nurses and 5 per cent each for employees in construction and sales. Especially in the case of production occupations and activities performed in direct contact with customers, patients, clients and so on, switching to telework was not an option.

Additional stress

The digitalisation of communication and working from home have reduced the risk of contagion but they are not automatically associated with a lower workload. On the contrary, replacing personal contacts with digital communication was perceived as an additional stress by one in three respondents (35 per cent); only 8 per cent felt this change had eased their workload.

Respondents’ assessments of telework were similar. One third (32 per cent) perceived an increased workload when working from home, 15 per cent a decrease in stress. The stress situation is strongly related to the other characteristics of the work situation: If there were children to look after, if the home was unsuitable for work and if there was insufficient training and technical support for the use of new digital work equipment, the additional workload was even more pronounced.

The digitalisation push and the spread of telework during the pandemic are often understood as harbingers of a new world of work, as if it were an experimental phase for forms of collaboration which should lead to a ‘new normal’ once the pandemic is over. Mobile, flexible working and greater self-determination of employees are supposed to be essential features of the new working world.

Workers’ self-determination

The DGB’s Good Work Index however makes two things clear. First, it shows that the use of new digital technology does not automatically lead to better working conditions. The decisive factor is the framework within which the technology is used, yet this has been given only secondary attention during the pandemic.

If the ‘new normal’ is to entail good working conditions, it will be important to include the interests of employees in work design at an early stage. In addition to questions of technical and ergonomic equipment, the main issue here is to strengthen workers’ self-determination in their work and to protect them against the removal of limits on working hours.

The great inequality in the world of work—increasingly apparent during the pandemic—also draws attention to the ‘old normality’, in which mobile work does not play a major role. More than 60 per cent of employees have continued to work exclusively at their company workplace.

A one-sided focus on mobile, mostly higher-skilled employees thus carries the danger of further fragmenting workforces. The goal of greater flexibility, self-determination and working-time sovereignty applies to everyone—indeed especially to those employees unable to do their work from home.

Rolf Schmucker is a social scientist and head of the DGB Good Work Index institute in Berlin. The institute conducts annual surveys of workers in Germany about their conditions.