For many years, Germany’s so-called “debt brake” has acted as a constraint on the economy. Since its primary function has been to prevent the state from financing investment through borrowing—contrary to the principles of the golden rule of fiscal policy—it would be more accurately described as an investment brake. The consequences are evident in Germany’s crumbling infrastructure, with dilapidated bridges, neglected school buildings, and an often dysfunctional railway system. Additionally, a growing housing shortage in major cities reflects inadequate support for social housing.

It took the decisive moments of recent weeks to overcome Germany’s deeply ingrained aversion to public debt and, in effect, suspend the debt brake by amending the constitution. Two key developments drove this shift. First, the new US administration made it unmistakably clear that it would no longer take primary responsibility for European security. Second, the outcome of Germany’s federal election meant that the centrist parties—the CDU/CSU, SPD, and Greens—would no longer command the two-thirds majority required to amend the constitution in the new Bundestag. This created urgency, as the constitutional change had to be enacted before the current parliament dissolves on 23 March.

Paradoxically, it was the conservative Chancellor-designate Friedrich Merz (CDU) who ultimately played a key role in dismantling the debt brake. What is striking is that the reform represents a significant leap forward, going well beyond what economists and policymakers had been advocating in recent months.

- A special fund of 500 billion euros will be established to finance additional investment in infrastructure, climate protection, and the green transformation of the economy. The funds will be allocated over a twelve-year period.

- The federal states will be granted an annual borrowing margin of 0.35 percent of gross domestic product (GDP), a flexibility that had previously applied only to the federal government under the existing debt brake rules.

- Defence expenditure exceeding 1 percent of GDP may now be financed through borrowing without restriction.

Persistent Concerns Over National Debt and Inflation

Predictably, the German media has responded to this reform with considerable scepticism, with little discussion of the economic opportunities it presents. Instead, the focus has been on concerns about rising national debt, which is indeed substantial in absolute euro terms. However, the more relevant economic question—how this affects the debt-to-GDP ratio—has largely been overlooked.

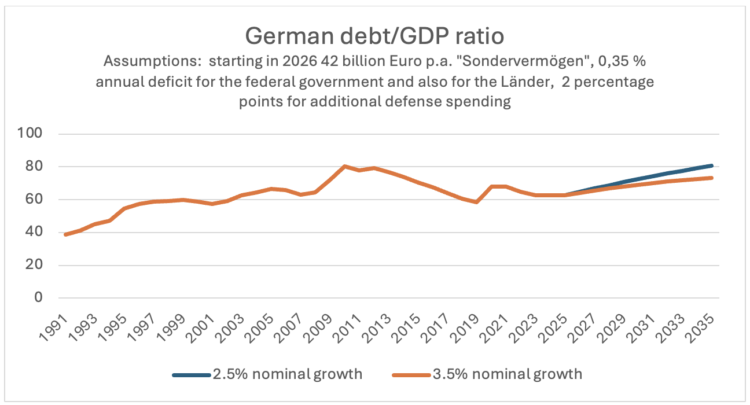

Assuming defence spending reaches 3 percent of GDP, projections for the debt-to-GDP ratio vary depending on nominal economic growth:

- If nominal GDP grows by 2.5 percent annually—comprising 2 percent inflation and 0.5 percent real growth—the debt-to-GDP ratio will rise from 63 percent in 2025 to 81 percent in 2035. This level corresponds to Germany’s previous peak in 2010 following the global financial crisis.

- If the reform generates additional economic momentum, leading to 3.5 percent nominal GDP growth, the debt ratio would increase to just 73 percent.

There is, therefore, little justification for warnings of a “debt collapse,” as expressed by Handelsblatt, especially since Germany’s debt levels would remain well below those of other G7 countries.

Concerns about inflation also feature prominently in the debate, with fears that such a large, debt-financed spending programme will drive up prices.

However, this perspective ignores key mitigating factors. A significant proportion of military equipment will need to be imported in the coming years, and Germany continues to run a current account surplus of around 6 percent of GDP. This limits the classic trade-off between “guns and butter,” a concept coined by Nobel laureate Paul Samuelson.

Labour availability is another central concern. In the construction sector, demand has declined sharply in recent years, creating substantial spare capacity. The government’s investment programme is therefore well-timed, not least in preventing an exodus of skilled workers.

Meanwhile, the defence sector could absorb workers from Germany’s automotive industry, which is experiencing profound structural upheaval. Increased defence spending also presents new business opportunities for firms in this sector.

Potential for Innovation and Growth

While fears over debt and inflation dominate public discourse, the economic potential of loosening the debt brake has received little attention. With real GDP currently no higher than in 2019 and a negative output gap of 1 percent, a boost to government demand appears well justified. Improved infrastructure will enhance productivity and competitiveness, while higher defence spending is expected to drive technological advancements in artificial intelligence, satellite technology, drones, and quantum computing. Given Germany’s relative weakness in these fields, the reform offers a rare opportunity to escape what some have termed its “mid-technology trap.”

The implications also extend beyond Germany. Whereas the previous government, under Finance Minister Christian Lindner, rigidly enforced adherence to the Stability and Growth Pact, there were no German objections when the European Commission proposed invoking the pact’s national escape clause.

Unintended Consequences for Financing Conditions

Despite the broadly positive assessment of the reform, one notable issue remains. The decision by the incoming CDU/CSU-SPD coalition has triggered an unusual surge in government bond yields, despite the European Central Bank (ECB) continuing to lower its key interest rates. If this trend persists, it could undermine the ECB’s objective of easing monetary conditions—an issue President Christine Lagarde highlighted on 6 March 2025 when she stated that “our monetary policy is becoming meaningfully less restrictive.”

One argument in favour of higher yields is that increased defence spending constitutes a significant demand shock, necessitating a more accommodative monetary stance. However, the timeline for increased defence expenditure to translate into higher demand across the euro area remains uncertain. Additionally, since 80 percent of European defence equipment is imported from outside the EU, the inflationary impulse is likely to be contained.

Furthermore, the European automotive industry suffers from substantial overcapacity, which could facilitate its transition towards defence manufacturing. Nevertheless, tighter credit conditions could temporarily slow economic activity in the euro area, hampering investment in much-needed technological renewal.

While it is too early to fully assess these effects, the ECB should monitor disruptions closely and, if necessary, activate its Transmission Protection Instrument (TPI). As the ECB itself has stated:

The TPI will be an addition to our toolkit and can be activated to counter unwarranted, disorderly market dynamics that pose a serious threat to the transmission of monetary policy across the euro area. By safeguarding the transmission mechanism, the TPI will allow the Governing Council to more effectively deliver on its price stability mandate.

Another key question is how increased defence spending will affect eurozone member states already burdened with high debt. As defence is a public good, a joint financing approach—modelled on NextGenerationEU—would be economically justified. A larger pool of jointly issued bonds would also enhance progress towards a Capital Markets Union by improving bond market liquidity.

A Pivotal Shift in Fiscal Policy

Germany has now undergone a paradigm shift that, until recently, seemed unimaginable. This transformation presents a significant opportunity, not only for Germany but for Europe as a whole, to strengthen security, foster innovation, and advance climate policy—without necessitating severe cuts to social spending. The success of the new government in capitalising on this potential will be critical. Failure to do so could risk the Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) emerging as the strongest party in the next general election.

This is a joint column with IPS Journal

Peter Bofinger is professor of economics at Würzburg University and a former member of the German Council of Economic Experts.