“Germany’s economy is in free fall,” warns Peter Leibinger, president of the Federation of German Industries (BDI). The German automotive sector, at the heart of its business model, is undergoing a disruptive process. Almost 50,000 jobs were lost in the space of a year (third quarter of 2025 compared with one year ago), with the number of automobile workers declining to a level not seen since 2011. The rest of the manufacturing sector is faring little better, with the total number of jobs falling by 120,000. A sign of the general weakness of traditional German businesses is that German GDP is no higher than it was six years ago.

With China now flooding European markets with cheap, attractive electric vehicles, these negative trends are likely to continue. Germany’s traditional manufacturing base is further challenged by its almost complete absence of a digital sector — internet platforms, semiconductor producers, and software companies. In this area, the United States is by far the dominant economy. Consequently, Germany is the European country most seriously affected by the “middle-technology trap” identified by economists as a threat to Europe in general.

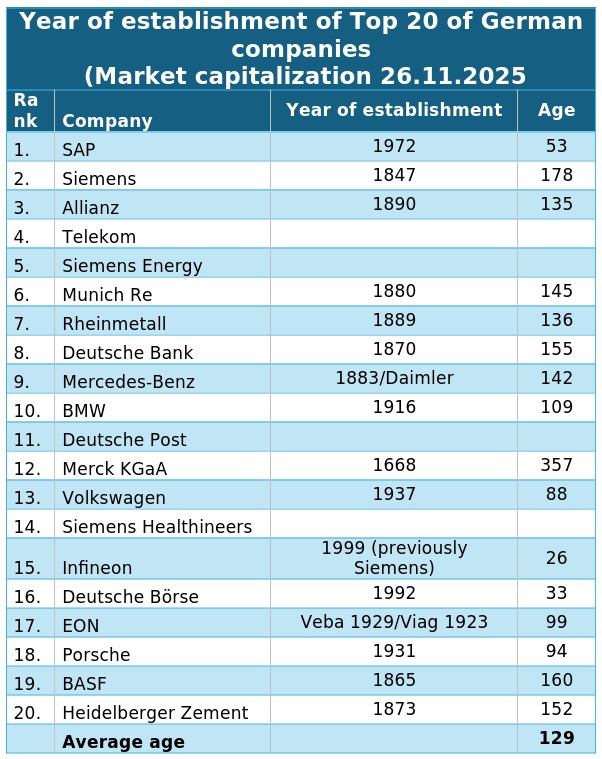

Germany’s unique position is illustrated by the average age of its top 20 firms (measured by market capitalisation): 129 years. While it is not negative that companies have successfully transformed over the decades, the problem is that new, globally relevant companies have not been developed in either the electronic and digital sphere or the field of renewable energies — batteries, electric vehicles, or solar panels, for example. This raises the question of why other countries, particularly the United States and China, have performed much better in establishing major companies outside the traditional manufacturing sector.

China planned its dominance; America hid its hand

For China, the answer is simple. In 2015, the country developed the “Made in China 2025” master plan, identifying core industries in which it intended to gain global leadership: information technology, computerised machines, robots, energy-saving vehicles, medical devices, and high-tech equipment for aerospace, maritime, and rail transport. Ten years later, it is clear that this strategy has been successful. China dominates the global market, especially in the supply chain of renewable energies. The threat that this strategy posed to Germany’s manufacturing sector was identified as early as 2016 in a study by the Mercator Institute for Chinese Studies. In an article for the Frankfurter Allgemeine Sonntagszeitung on 12 August 2017, I warned of the challenges posed by China’s industrial policy for Germany. In response, my fellow members of the Council of Economic Experts criticised me, questioning my economic expertise.

But what about the United States? Here, the dominant narrative seems to support the view of many German economists that innovation cannot and should not be managed by the government, which is supposedly unable to “pick winners.” This narrative is supported by famous stories about the origins of big tech companies, which often depict their founders as starting their businesses in a garage: Bill Gates in 1975 (Microsoft); Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak in 1976 (Apple); Larry Page and Sergey Brin in 1998 (Google).

This seems to confirm the Hayekian view of competition as a discovery process, the idea that a market system has an innate capacity for innovation as long as it is not disturbed by government regulations and burdensome taxes. The “garage” narrative is presented in the 2018/19 Annual Report (paragraph 158) of the German Council of Economic Experts:

In order to be sustainably successful, however, an innovation location should refrain from a guiding industrial policy, which sees it as a state task to identify future markets and technologies as strategically important (…). It is unlikely that policymakers have sufficient knowledge and understanding of future technological developments or changes in demand to make this a meaningful long-term strategy. If the government is concerned about sustainable progress, it should rather rely on the decentralized knowledge and the individual actions of various actors of the national economy.

However, this raises the question of why Germany has been unable to develop similar garage success stories. There has certainly been no shortage of garages or very smart young people. To understand the digital dominance of the United States, one must look beyond the standard narrative. The explanation lies in the comprehensive yet “hidden” industrial policy pursued by the US government in the 1950s and 1960s. In the words of Wade (2014):

The dominant approach to selective industrial policy took the form of government support for ‘basic’ research in a plethora of military laboratories. Hence the quip: ‘America has had three types of industrial policy: first, World War II; second, the Korean War; and third, the Vietnam War.’ The focus on ‘basic’ and ‘military’ research avoided the ideological issues surrounding industrial policy because even market fundamentalists accepted that the government should fund the development of new weapons and intelligence systems.

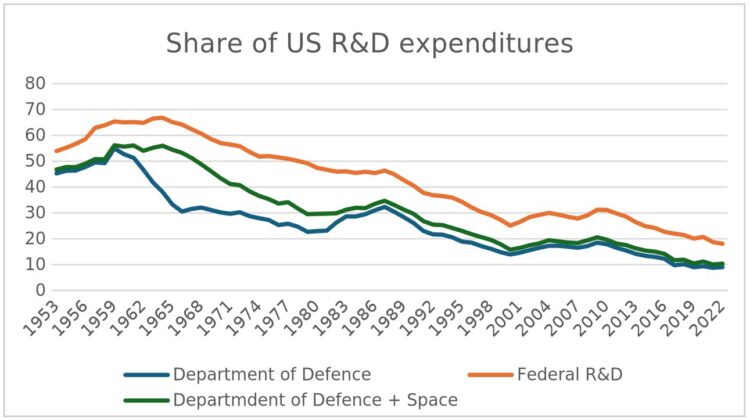

Data on US R&D spending illustrates the significant contribution of military R&D spending in the 1950s and 1960s. Expenditure by the Department of Defense and NASA accounted for over 50 per cent of total R&D spending in the United States. This spending’s importance becomes evident when considering that, in 1960, US defence spending accounted for 36 per cent of global R&D expenditure.

Thus, contrary to the mainstream narrative, it was the US government that had a clear strategic vision of boosting electronic computers, computer software, and semiconductor components, giving birth to the internet and, more recently, digital platforms. US industrial policy remains active to this day, as evidenced by In-Q-Tel (or IQT), the CIA’s investment arm, which describes its role as follows:

For more than a quarter of a century, IQT has delivered significant mission impact by building a unique — and uniquely powerful — not-for-profit global investment platform that accelerates the introduction of groundbreaking technologies to enhance the national security and prosperity of America and its allies.

Unfortunately, the misconception of the US digital agenda continues to shape economic thinking in Germany to this day. Katherina Reiche, the Minister for Economic Affairs and Energy, in particular, has a deep belief in the virtues of a free market economy. At a recent symposium, she argued that the government should focus on its core competencies, such as external security, education, and infrastructure. She believes that subsidies and funding programmes should be rigorously scrutinised. In her view, competition is the most important driver of innovation (“prosperity through competition”), although she also acknowledged that US tech giants are a key source of economic dynamism in America.

The debt brake’s missed opportunity — and hidden potential

The lack of a comprehensive strategy for transforming the German economy is particularly damaging as the reform of the so-called debt brake in March 2025 created an opportunity to actively promote fundamental innovations. However, due to this conceptual void, much of the additional financial space will be used to lower the energy costs of existing firms (around €30 billion in the 2026 budget), while only €4.5 billion will be available for the so-called “HighTech Agenda Deutschland.”

Therefore, as long as most German politicians and economists continue to adhere to a flawed concept of growth and innovation, the outlook for the German economy will remain bleak. Caught between a rock (China) and a hard place (the USA), its manufacturing sector will continue to shrink without a corresponding rise in new competitive technologies.

Is the situation really that hopeless? There is still a glimmer of hope. The reform of the debt brake makes it possible for all defence expenditures exceeding one per cent of GDP to be financed with debt. There is no limit to this. This creates an opportunity to use the defence sector to promote new technologies that can be used for purposes beyond the military. In this regard, Germany could adopt the US model of “hidden” industrial policy to help it escape the middle-technology trap.

This is a joint column with IPS Journal

Peter Bofinger is professor of economics at Würzburg University and a former member of the German Council of Economic Experts.