European Union citizens are experiencing inflation not seen for decades. In Germany it has reached double digits at 11 per cent, while in Austria the rate is 9.3 per cent. These rates are due to the disruption in supply chains and the shortage of fossil resources—triggered by the coronavirus crisis and the Ukraine war—on which the two countries were extremely dependent until recently. Prices are exploding not only in energy supply but also in all other essentials, including food.

At the same time, companies in certain sectors are making excess profits due to the shortage of strategic resources. Since market mechanisms are no longer working in such a constellation, it is the task of the state to intervene with regulatory policy.

The American energy giant Exxon Mobile announced earnings of $17.9 billion in the second quarter of 2022 compared with $5.5 billion in the first, tripling its profit. BP’s first-quarter profit was three times last year’s $9.1 billion. The German energy group RWE increased its profit by more than a third to €2.8 billion in the first half of 2022. And the Austrian company ÖMV recorded a profit of 124 per cent in the first two quarters.

The United States president, Joe Biden, said: ‘We will make sure that everyone knows Exxon profits.’ Implicit in his reproach was that the corporation’s profit was not related to enhanced performance, achieved by investment and technological progress. On the contrary, companies in strategic oligopoly and monopoly positions appear to be exploiting consumers’ dependency in the crisis and charging unreasonable prices for products for which there are no alternatives.

‘Exploiting the war’

This has become known as ‘greedflation’ in the US. In Europe, meanwhile, the president of the European Commission, Ursula von der Leyen, declared war on the phenomenon in her address on the state of the union: ‘In these times it is wrong to benefit from extraordinary record profits by exploiting the war to the detriment of consumers.’

In the traditional view of the market, focused on redressing imbalances between supply and demand, unlimited profit maximisation by companies is a logical consequence and cannot be described as greed. Greedflation, on the other hand, calls into question whether high selling prices are actually offsetting higher production costs or merely reflect rent-seeking behaviour enabled by monopolistic or oligopolistic power to set the market terms. Even advocates of a ‘free-market’ economy can doubt the self-regulatory power of markets so structured.

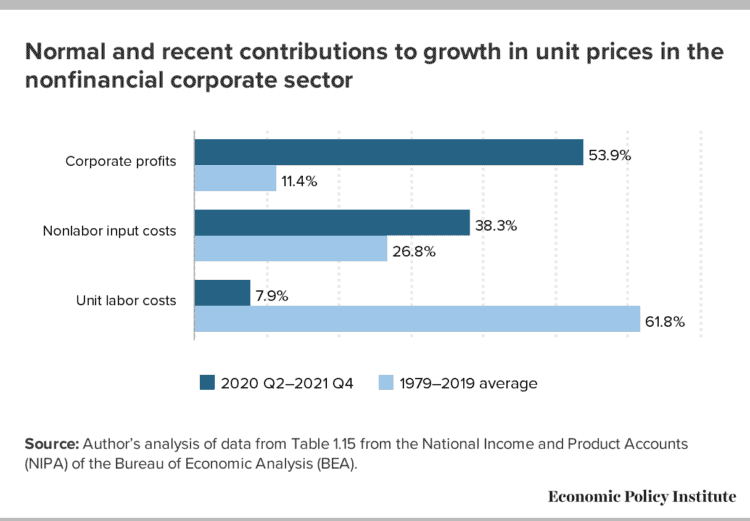

The pricing power of companies in monopolised markets is so great that inflation is accelerated. The windfall gains made will almost inevitably lead to a social crisis unless inflation is cushioned by higher wages—especially taking into accout that since 2020 the wage-price ratio has been in a downward spiral. In the US, for example, 61.8 per cent of price increases between 1979 and 2019 but only 7.9 per cent since 2020 can be attributed to wage increases.

So, are we entering a time ‘when action matters and history is made’? A time when German and British unions enter wage negotiations with a demand for a 10 per cent increase or French industrial unions demand a 25 per cent increase in the minimum wage?

Windfall taxation

The profits-wage race can be dampened by a windfall-profits tax. Disproportionate gains without a significant increase in performance or increase in production costs should be ‘taxed away’.

In the US, this approach was put on the agenda by the left-wing senator Bernie Sanders in March. The idea is not new: during the two world wars, among other things, an excess-profit tax of up to 95 per cent was introduced in the US to skim off the cream companies made as a result of the extraordinary war events. The instrument was last used during the oil crisis in the 1980s.

In the meantime, a number of EU member states have introduced an excess-profit tax. In the UK the rate is 25 per cent. In Spain it is assumed that the tax will accrue €7 billion over the next two years. Norway expects 50 per cent higher tax revenue this year.

In Austria, political approval is cautious, although the Austrian Trade Union Federation assumes that €4-5 billion per year could thus be generated. But many hesitant governments may be overtaken by the EU: in its proposed regulation on emergency measures in response to high energy prices, the commission proposes a ‘solidarity levy’ on excess profits in the fossil sector this year. It should amount to 33 per cent of taxable profit.

From a trade union perspective, one thing is clear: the myth that companies ‘deserve’ high profits, regardless of market structure, is untenable in times of war. As von der Leyen rightly said, ‘Profits must be shared.’ Trade unions will take the president of the commission at her word—and make sure these words are not empty.