This year’s Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel honours Ben Bernanke, Douglas Diamond and Philip Dybvig. In the view of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, the laureates ‘have significantly improved our understanding of the role of banks in the economy’.

But what is the role of banks in the economy? The academy describes it this way: ‘To understand why a banking crisis can have such enormous consequences for society, we need to know what banks actually do: they receive money from people making deposits and channel it to borrowers.’ According to this view, banks are thus pure intermediaries or dealers of savings between saving households and investing companies. It is a view widespread in economics today but there has long been a completely different theory of the function of banks.

This was formulated, among others, by Joseph Schumpeter. In his Theory of Economic Development (published in German in 1911), Schumpeter wrote: ‘The banker, therefore, is not so much primarily a middleman in the commodity “purchasing power” as a producer of this commodity.’

In this vein, in 2014 the Bank of England affirmed: ‘Money creation in practice differs from some popular misconceptions—banks do not act simply as intermediaries, lending out deposits that savers place with them.’ Three years later, the Deutsche Bundesbank similarly spoke of the ‘popular misconception that banks act simply as intermediaries at the time of lending—ie that banks can only grant loans using funds placed with them previously as deposits by other customers’.

Surprisingly, the academy did not address this alternative view in its explanatory paper. Instead, it even presents Schumpeter as a representative of the intermediation theory.

Underlying models

To understand both theories, it is necessary to look at the design of the underlying models. The intermediation (or loanable-funds) theory presents itself as a pure-commodity theory or a ‘real analysis’, as Schumpeter put it in his History of Economic Analysis. In this model, there is only one all-purpose asset, which can be used interchangeably as consumption good, investment good or ‘capital’. Central are the consumption decisions of households, to consume or save the asset. Households channel non-consumed or saved asset (‘capital’) directly, or via banks, to investors, who then invest it. As a result of the investment, a larger quantity of the unit good becomes available.

It follows from the model’s assumptions that banks are not able to produce that good themselves. Their role is therefore limited to facilitating its transfer between savers and investors. Due to the dual nature of the asset, as real asset and as ‘capital’ or savings, the real economic sphere is thus identical to the financial sphere. There is no room for money as an independent asset or for financial decisions that are separate from the consumption and investment decision. Considering these assumptions, it seems ambitious to derive insights into the functioning of banks and the financial system from a model which has no independent role for money or other financial assets.

Monetary approaches, or what Schumpeter called ‘monetary analysis’, recognise real assets (consumption and investment goods) as different from monetary assets (bank deposits and bonds), as in the ‘IS/LM’ model, for example. Besides consumption and investment decisions, there are independent financial decisions: lending by central banks and commercial banks and bond purchases by non-banks.

Crucial to these models is that banks do not need ‘savings’ or deposits to lend. Rather, it is the other way around: when a bank makes a loan, deposits are created. Banks are thus—exactly as described by Schumpeter—‘producers of purchasing power’.

Of course, lending to an individual bank means that the deposits it creates are used for transfers to other banks. For the banking system as a whole, however, deposits remain unchanged. The deposit loss of the lending bank is compensated by interbank loans or refinancing loans from the central bank.

The fact that this process can be disrupted in crises, as described by Anat Admati and Martin Hellwig, does not fundamentally call it into question and does not justify the validity of the intermediation theory. This also applies to their argument that cash withdrawals could limit the credit expansion of banks. As central banks control the credit expansion of commercial banks with their policy rates, they are willing to provide passively the amount of central-bank money (including cash) the banking system requires.

Banking crises

For the analysis of banking crises, the distinction between the two model approaches is critical. The main cause of banking crises is usually excessive lending by banks, which leads to overheating, especially in the property sector. The subsequent collapse in this market leads to loan defaults and bank insolvencies. The intermediation model cannot however explain such an inflation of credit volume. Household savings, which are the only source of credit in this model, are a very inert variable.

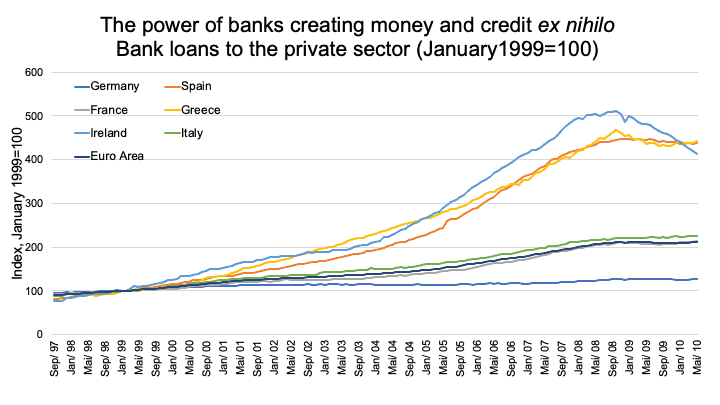

This is different in a monetary model, where banks are able to generate excessive credit expansion over a prolonged period. When property prices rise, the collateral for loans increases. Income from lending brings profits for the banks and increases their capital. The dynamics of these processes can be seen in Spain, Greece and Ireland before the financial crises, where bank lending expanded by 450-500 per cent (see graph).

It is a characteristic of the intermediation literature that, as in the work of Bernanke—former chair of the United States Federal Reserve—it can explain the crisis phases but not the processes that led to them. This also applies to the work of Diamond and Dybvig, who represent banks as a kind of insurance company. They identify the risks of this insurance contract but are unable to deal with the dangers of excessive lending.

Here one can learn more from Schumpeter. In Business Cycles (published in 1939), he clearly identified these problems associated with the power of banks to create credit:

Once a prosperity has got under sail, households will borrow for purposes of consumption, in the expectation that actual incomes will permanently be what they are or that they will still increase; business will borrow merely to expand on old lines, on the expectation that this demand will persist or still increase; farms will be bought at prices at which they could pay only if the prices of agricultural products kept their level or increased.

It is hard to understand how the Swedish academy could decide to honour a theory which—due to its ‘real analysis’—is unsuitable to represent monetary processes in reality. In terms of economic policy, it makes a fundamental difference whether banks are merely intermediaries of savings or insurance companies or whether they are producers of purchasing power. The ‘real analysis’ was an important factor in the inability of the economics profession to anticipate the Great Financial Crisis in time.

After that painful experience, to extol with the Nobel prize for economics the intermediation approach to banking is akin to posthumously offering Ptolemy the prize for physics—because he discovered that the sun revolved around the earth.

This is a joint publication by Social Europe and IPS-Journal

Peter Bofinger is professor of economics at Würzburg University and a former member of the German Council of Economic Experts.