As pressures grow on Europe’s hospitals, lessons must be learned from social dialogue during the pandemic.

The pandemic made us acutely aware of how dependent society is on essential workers. We felt deep gratitude towards workers in healthcare especially, because they worked ceaselessly in often difficult conditions.

But this most valued of sectors is in danger of failing society’s needs in the future, because of growing labour shortages. Working conditions in healthcare are increasingly challenging, pushing highly qualified staff out of the sector and deterring new entrants.

How should this bleak situation be tackled? Social dialogue and collective bargaining played a crucial role in ensuring the effective functioning of hospitals during the pandemic. And social dialogue could be the solution to maintaining and building a health workforce fit for the ‘3D’ transition: digitalisation, decarbonisation and demography.

‘Strained jobs’

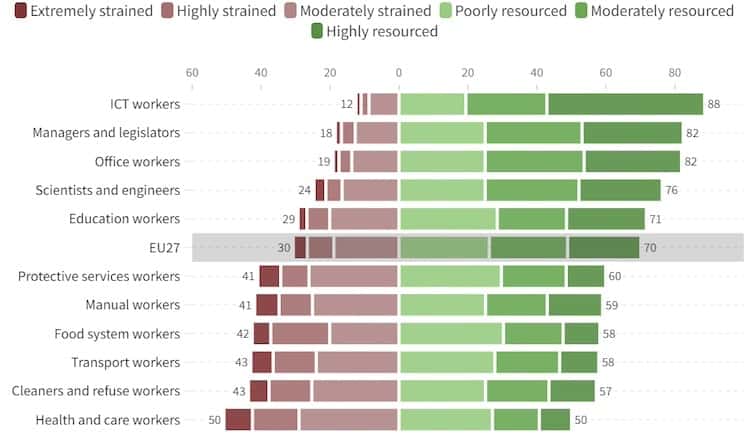

Based on its research into working conditions during the pandemic, Eurofound identified 11 groups of workers essential to the functioning of critical services. Of these, health and care workers, predominantly women (76 per cent), had the poorest job quality overall.

As the bar chart shows, half of these workers were in ‘strained jobs’—those in which the job demands surpassed the job resources, putting the health and wellbeing of workers at risk. The high demands were a combination of physical risks (including handling or being in contact with infectious materials) and obligations (such as lifting or moving people), exposure to adverse social behaviour (verbal abuse, bullying, harassment and violence, and unwanted sexual attention) and work intensity (including working at high speed and being exposed to emotionally disturbing situations).

Proportions of essential workers in the EU in strained and resourced jobs by group, 2021 (%)

While health and care workers were more likely to report receiving the support of colleagues and to display high engagement—indicative of their vigour, absorption in and dedication to their work—the sustainability of their work was questionable: half reported that their health and safety were at risk, and more than half reported exhaustion or being at risk of burnout. These workers experienced a volatile combination of poor job quality and poor job sustainability. This is reducing the attractiveness of jobs in the sector and contributing to rising staff shortages.

Social dialogue

Physical and psychosocial risks are important aspects of health and care workers’ conditions which could be addressed by inclusive and effective social dialogue between workers and their representatives, on the one hand, and providers in hospitals and health and care more broadly, on the other. The social partners do not typically venture into these areas: traditionally, collective bargaining tends to focus on pay and working time. During the pandemic, however, social dialogue moved on to less familiar ground.

Research by Eurofound shows that in several European Union member states social dialogue played a prominent role in addressing some of the challenges posed in hospitals. The social partners tackled issues such as the adaptation of work organisation and reallocation of staff to secure sufficient capacity. They also agreed measures to protect the health and safety of the workforce.

This happened in those countries with well-established social-dialogue institutions and longstanding co-operation between the social partners: Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, Germany, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Norway and Sweden. In these countries, negotiations between the social partners were vital for, among other things, the changes to work organisation required to tackle the health crisis and the successful allocation of additional resources. In some countries where social dialogue has typically played a background role, however—Bulgaria, Czechia, Cyprus, Estonia and Malta, for example—it also proved useful and efficient in helping to secure workforce capacity in hospitals.

Increasingly concerned

The pandemic exacerbated staff shortages and in its wake the problem is intensifying, with international competition for the recruitment of health workers increasing. The social partners in the hospitals sector are increasingly concerned about the impact of high stress and heavy workloads on staff retention—these are often why workers leave the sector while new staff are difficult to recruit.

In a context of population ageing and climate change, which will likely increase the demand for healthcare and emergency services, the capacity of the sector to continue to provide an essential and quality service in the future is open to question. The involvement of the social partners is crucial to addressing these concerns.

Eurofound’s findings confirm that when the social partners engaged with the challenges faced by hospitals during the pandemic solutions were developed more quickly and effectively. Healthy functioning of social dialogue and collective bargaining is crucial for a strong and healthy hospitals sector, and for the advancement of healthcare more broadly—foundations on which the EU’s preparedness for the challenges ahead rests.