The left-wing German politician Sahra Wagenknecht is launching a new party, Bündnis Sahra Wagenknecht—für Vernunft und Gerechtigkeit (for reason and justice). With its likely ‘left-authoritarian’ agenda, BSW looks poised to shake up the German system.

The tables have turned. Back in 2016, Wagenknecht was leader of the opposition in the Bundestag, representing the left-wing party Die Linke. At a conference in Magdeburg, after contradicting her own party on several issues, anti-fascist protesters slapped a chocolate pie in her face.

Eight years later, Wagenknecht gave a press conference announcing the foundation of her own party. BSW is currently trouncing her previous comrades in the polls.

Attracting disgruntled voters

The development has the potential to alter radically Germany’s party system, because the new party could entice votes from almost all others. Apart from the radical left, BSW challenges the centre-left/liberal governing coalition, attracting voters disgruntled with unpopular policies and economic woes. Culturally, it competes with the main protagonist of anti-government sentiment, the radical-right Alternative für Deutschland (AfD), through harsh criticism of recent progressive government policies. Beyond Germany, it illustrates a wider dilemma and conflict brewing within the European left: whom to represent.

Wagenknecht pledges allegiance to a (supposedly) forgotten, under-represented voter. This voter has been left behind by fiscally conservative policy and overwhelmed by cultural changes in society. They may favour a strong welfare state with generous benefits but not a welcoming immigration scheme.

More abstractly, Wagenknecht’s target voter is an economic leftist but a cultural conservative, or even an authoritarian. Europe’s leftists have long fought over whether to prioritise this prototypical voter (the ‘left authoritarian’) over their other strong support base (voters with strongly leftist and culturally progressive views). Most radical leftist parties in Europe opted for the latter, leaving the left-authoritarians without a clear political home.

Missing left authoritarian

When citizens cannot find any political force which aligns with their views, they become alienated from the system as a whole. They are more prone to abstain from elections, to vote for populist parties and to hold negative views about democracy. And from a normative standpoint, failing to represent a large swath of people is simply not a good idea.

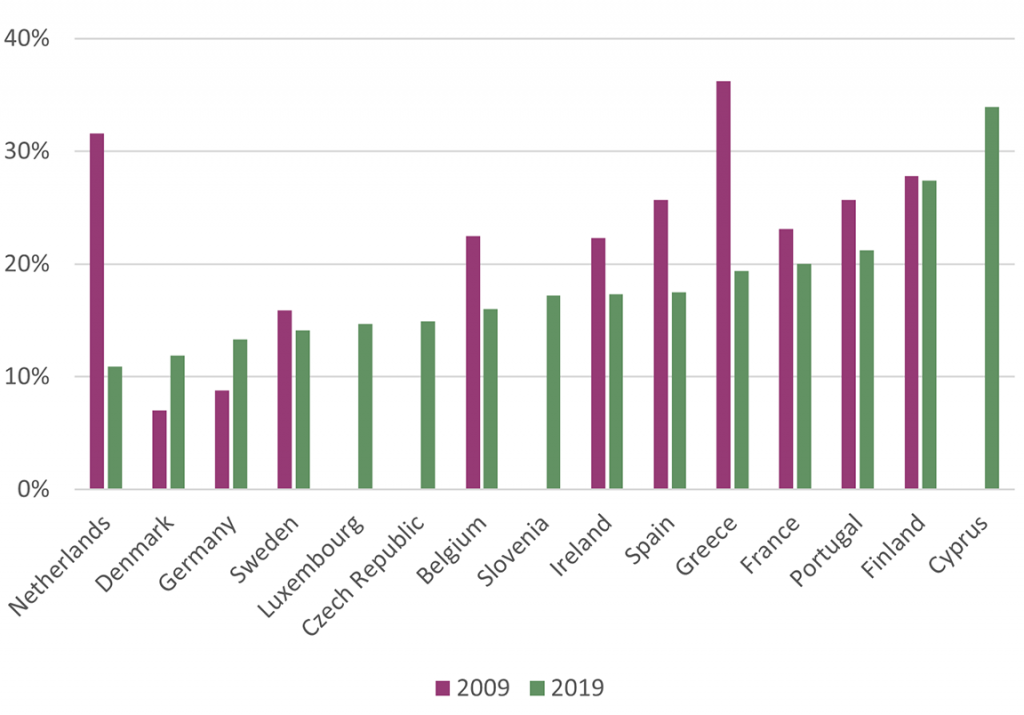

However, whether these voters really are a large swath of the population depends on the country. While they do represent a plurality in some countries, their share in others remains in single digits. And across western Europe, the past decade has seen a clear downward trend. The only countries with (small) increases in left authoritarians are those which had small shares to begin with. Overall, in most countries, fewer people identified with left-authoritarian standpoints in 2019 than in 2009 (Figure 1):

Figure 1: share of left-authoritarian voters

Strikingly, the under-representation of left authoritarians is not a universal phenomenon; rather, it is primarily western European. Central and eastern Europeans have known plenty of such parties since democratisation. Among the region’s radical-leftist parties, communists in Moldova and the Czech Republic remain staunch authoritarians, just like the communists in Ukraine (before their ban in 2015). And the social-democratic parties of Bulgaria, the Czech Republic and Slovakia, among others, run on authoritarian platforms.

However, most authoritarian radical-leftist parties have lost voters in recent years. In the Czech Republic, the communists recently lost all their seats in parliament. In Moldova, they merged with the social democrats to avoid the same fate.

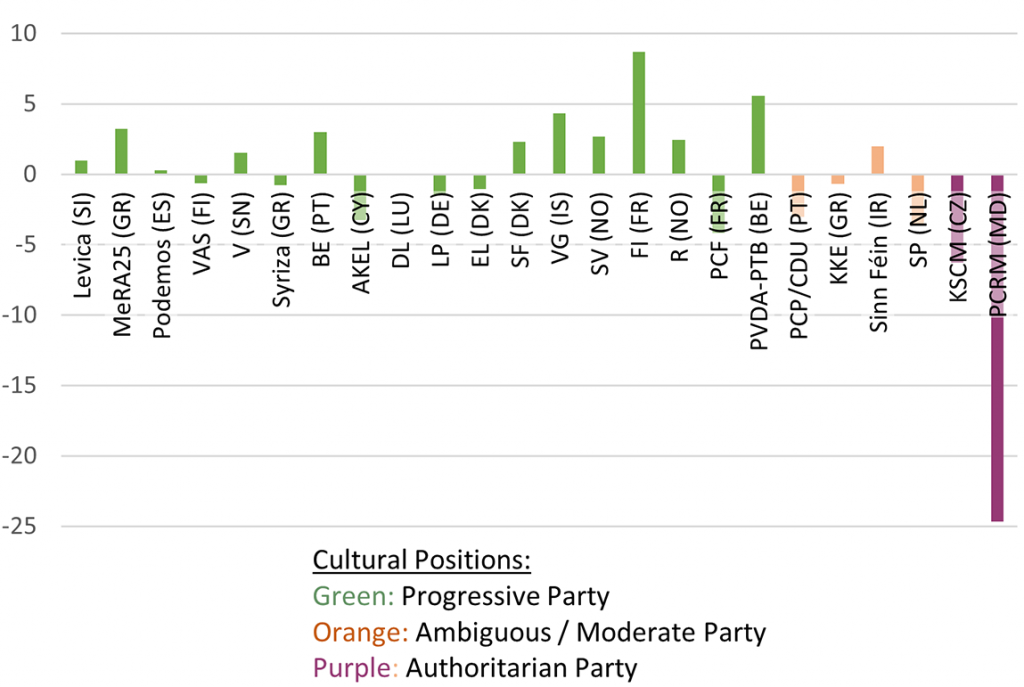

Some of their western-European counterparts do not focus strongly on cultural progressivism. These parties are not doing too well, either. The communists of Greece and Portugal have remained in mid-single digits in recent elections. The Dutch Socialist Party vote has stagnated and declined since 2006 (with a recent poll plummeting to about 3 per cent). All in all, for those parties already trying to appeal to left authoritarians, the recipe is not working well (Figure 2).

Figure 2: vote shares of radical-left parties—2004 versus 2021

Crowded field

Some recent polls predict a hopeful start for Wagenknecht’s new party, with figures in the lower double digits. However, this is well below the high hopes suggested by tantalising earlier polls.

BSW is currently a ‘registered association’; the party has yet to be formally founded. At this stage, it remains centred around Wagenknecht’s persona rather than operating on a clear policy platform. But we can assume BSW’s positions will largely match those of Wagenknecht in the past. These were hardline economic leftism combined with a restrictive immigration policy, conservative views on social issues and strong populist language.

For one thing, it is far from certain whether left authoritarianism is here to stay among voters (even if Germany is an exception, having experienced a slight increase over the past decade). Moreover, left-authoritarian parties have declined even faster than the people who vote for them. Hence, it is not a given that left-authoritarian voters will automatically rally behind a similar party.

Lastly, in terms of populism, the party is not unique. Populist parties, most prominently on the right, have mushroomed across Europe. Wagenknecht’s new party is entering a crowded field on the populist and cultural right, and it is unclear whether there remains much of an authoritarian field on the left. And as many other former hopefuls across Europe will attest, it is hard to maintain a party on the basis of populism alone.

This article was originally published at The Loop and is republished here under a Creative Commons licence