Will the 2022 EU directive on adequate minimum wages, if upheld by the European Court of Justice despite the recent Advocate General’s negative opinion, finally compel Italy to adopt a national minimum wage? More broadly, what factors drive a nation to embrace minimum wage legislation? Why are trade unions – typically champions of workers’ rights – often wary or outright opposed, and what might persuade them to alter their stance?

Wage-setting regulations exhibit a notable “stickiness”; no country has yet dismantled a minimum wage, and very few have introduced one during “normal times,” typically only in the aftermath of significant upheaval such as war or revolution. Therefore, it is crucial first to examine how these regulations are embedded within distinct institutional models and historical contexts. The UK and Germany offer pertinent precedents: both adopted a minimum wage only after considerable political and social transformations, with trade unions playing a pivotal yet ambivalent role. Italy, in contrast, remains at a critical juncture, with its collective bargaining system facing challenges that have not yet precipitated legislative change.

Why Minimum Wages Shake the Foundations of Industrial Relations

While 30 out of 38 OECD countries have implemented national minimum wages, the remainder, notably Italy, Austria, and the Nordic nations, place their faith in collective bargaining. Within this latter group, a significant concern among trade unions is that a minimum wage could prove counterproductive, potentially undermining collective bargaining and the influence of labour organisations. This was for a considerable period the prevailing sentiment among British and German unions, too.

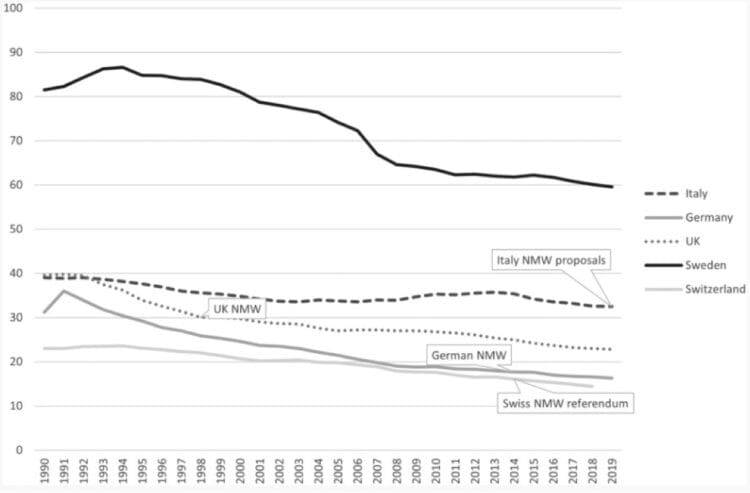

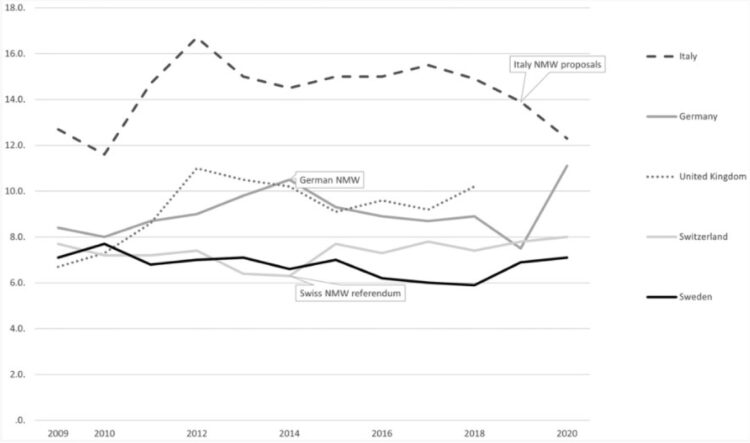

The catalysts for policy shifts in the UK and Germany were acute new challenges: escalating in-work poverty and the erosion of collective bargaining (see Figures 1 and 2, comparing them to countries that have not adopted a minimum wage).

Figure 1: Trade union density (source: ICTWSS)

Figure 2: Employees at risk of poverty (%) (source: Eurostat)

Significant shocks were necessary to prompt stakeholders to recognise that these emerging issues demanded novel solutions. In the late 1980s, the Thatcher government’s policies led British unions to transition from opposing to supporting minimum wages. Similarly, in the late 2000s, the Hartz reforms, coupled with German reunification, spurred German unions to revise their stance. The established institutional frameworks – multi-employer bargaining and wage councils in the UK, and employer associations alongside robust unemployment benefits in Germany – were significantly weakened. Furthermore, a degree of labour strength was required, manifested in a centre-left government and declining unemployment rates, though not necessarily in the form of strong associational power (see Figure 3). However, labour strength alone is not a sufficient condition for the adoption of a minimum wage, as history shows instances in other periods and countries where strong labour movements did not advocate for such a measure. For trade unions, needing a minimum wage often represents a strategic retreat rather than an advancement.

Figure 3: Unemployment Rate (source: Eurostat)

Italy at a Crossroads

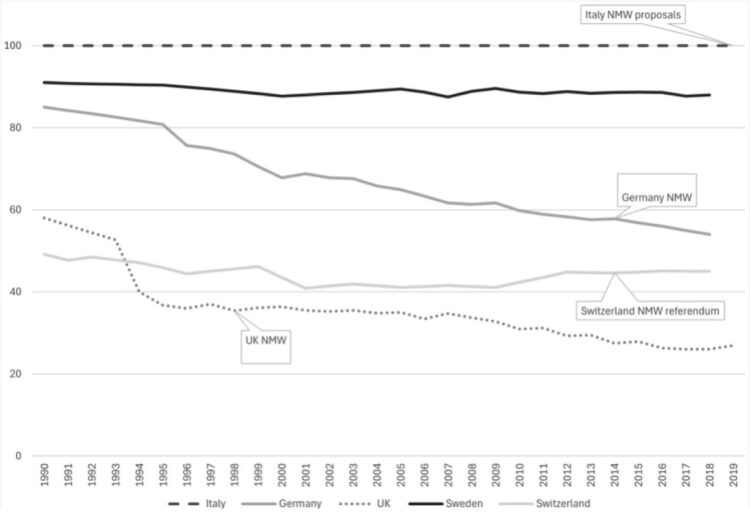

Why has Italy, a country with high levels of in-work poverty, not followed suit? Much of the explanation lies in its unique institutional legacy. Wage regulation is primarily achieved through a combination of collective agreements and court decisions that extend their application to all employers, theoretically providing for 100 percent collective bargaining coverage (see Figure 4).

Figure 4: Collective Bargaining Coverage and time of minimum wage introduction (source: ICTWSS Database)

Nevertheless, signs of strain are increasingly evident in the form of low and stagnant wages, as well as a proliferation of “pirate agreements” that erode established standards. Despite this, Italian unions remain cautious (CGIL and UIL) or opposed (CISL) to a minimum wage, fearing that it could discourage courts from imposing collective agreements, thereby weakening the entire system and the unions’ own influence. Italy’s situation underscores a crucial lesson: institutional change is not a mechanical consequence of economic or political necessity; it also necessitates shifts in the perceptions and priorities of key stakeholders. While a minimum wage might offer a solution to combat in-work poverty, the fundamental question is whether existing institutions can adapt to evolving needs without compromising their effectiveness. And Italian unions, lacking the transformative shocks experienced by their British and German counterparts, may still believe that the potential losses from altering the institutional framework outweigh the gains.

Conclusions

Across Europe, the issue of low wages and labour market inequalities is a growing concern. However, as acknowledged by the EU Directive on minimum and adequate minimum wages, this problem does not automatically necessitate national minimum wages, provided that functional equivalents exist. Nor is the emergence of opportunities for change within the political sphere sufficient to automatically reshape the industrial relations system. As long as it remains feasible, social partners will favour an institution they directly control over one where their influence is ultimately limited, even if they are initially granted a role.

Employer criticism of the national minimum wage in Germany and the UK mirrored the concerns expressed in Italy today; in the former two cases, this opposition diminished under pressure, and by 2022, there were indications that a similar shift might occur among Italian employer organisations. More critical for the introduction of a minimum wage is the evolution of trade unions’ positions, at least as long as they retain significant veto power. The sceptical stance of Italian unions, sometimes described as unreasonable in Italian debates, reflects a broader logic within industrial relations. Even though there is no conclusive evidence that minimum wages necessarily reduce union density, unions understandably guard their influence jealously, and institutional differences mean that lessons from other countries need to be taken cautiously. Ultimately, it is not solely a question of whether unions possess power; what matters most is whether they perceive specific institutions as resources that enhance their power.