Left and right governments used to pursue distinct macroeconomic policies, with left governments associated with fiscal profligacy (and redistributive policies). Over the past few decades, however, left and right have converged, with no notable differences in their fiscal policies.

Even in times of crisis, when we might expect divergence, left and right fiscal policies appear indistinguishable. For instance, in reaction to the global financial crisis of 2007-08, both left and right governments endorsed austerity policies. While the news is already bad for the core constituencies of left parties, the reality is even worse.

My recent study scrutinises this convergence. It focuses on the role of government partisanship in fiscal-policy responses to international economic crises in advanced democracies. I find that, over the course of the business cycle in the two last crises, left governments pursued more restrictive fiscal policies than their right-wing counterparts. This amounts to no less than a reversal of traditional partisan effects.

Financial-market constraints

The switch in partisan effects is caused by constraints imposed by financial markets. My analysis shows that market actors were concerned about deficits in 1990-94 and about deficits and spending in 2008-13. Specifically, statistical analysis suggests that (indebted) left governments were less likely to engage in fiscal stimulus than right governments during the protracted early-1990s recession.

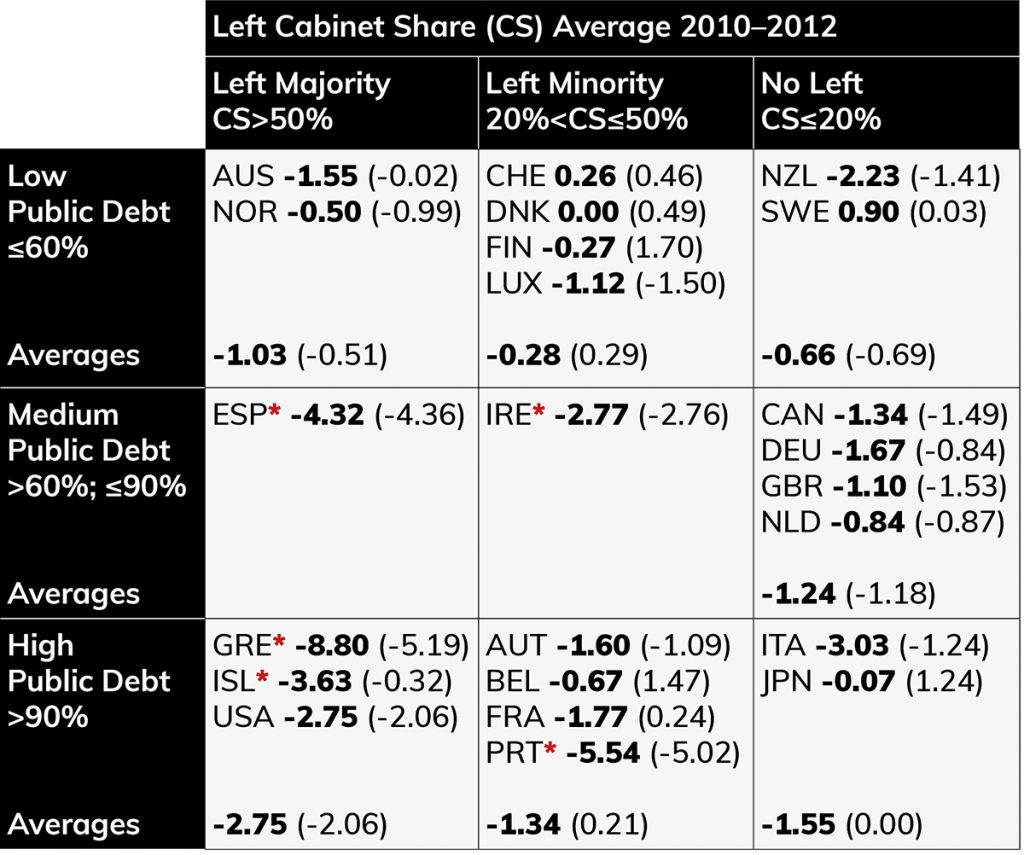

During the subsequent crisis, bond-market investors compelled indebted left governments, by comparison with their right-wing counterparts, to stimulate less forcefully by way of spending increases in 2008-09 and consolidate more forcefully by way of cuts during 2011-12. Meanwhile, investors more strongly constrained left governments to consolidate by reining in spending than did right governments in the (fragile) recovery of 2010.

Fiscal policy outputs under different constellations of partisanship and debt in 2011-12

Government reactions in the early 1990s and late 2000s / early 2010s set them apart from responses to earlier crises. If anything, fiscal-policy responses in the early 1980s were reminiscent of traditional partisan patterns.

Left governments stimulated more during downturns, although the models are statistically insignificant. They also consolidated less during the early recovery of 1984, irrespective of a country’s exposure to financial markets. Low levels of indebtedness and limited capital-market openness in the early 1980s explain the absence of reversed partisan effects.

Financial-market constraints are stronger for left than right governments at high debt level. This is because left governments have lower credibility as sovereign debtors.

Bond-market actors are concerned about debt financing, defaults or incentives to inflate away public debt. In the view of market participants, these are the trademark of left governments. To maintain access to borrowing at similar rates to right governments during debt crises, left governments are compelled to impose more austerity. It’s the price left-wing governments must pay for the ‘credibility gap’.

Fiscal policy central

Fiscal policy is not only crucial for economic stability; it also reflects a government’s objectives, as enshrined in the national budget. With the advent of democratic capitalism, the economic dimension has been the main axis along which the political space is structured. It has defined distinguished party positions, with left parties more in favour of state intervention.

The core constituencies of left parties are more supportive of government redistribution. Conversely, individuals believe that left parties champion such policies more than right parties.

The legitimacy of the party system and the democratic order itself still hinge on traditional partisan effects. The ideological mix with political partisanship during hard times is certainly confusing to ordinary citizens.

Voting with their feet

It is tempting to see the switching of partisan effects during major crises as one of the origins of our contemporary political crisis. Western democracies have been battling with extraordinary political discontent in the aftermath of the global financial crisis.

The most visible manifestation is the changing party-political landscape across advanced democracies. The clearest symptoms are the sharp drop in support for mainstream parties from the left and the right, the surge in support for established far-right parties, the eruption of challenger parties and the emergence of fault lines within mainstream parties which pose an existential threat to them.

Populist far-right parties such as the AfD in Germany have made particularly pronounced electoral gains across northern Europe. In southern Europe, while the challenger Five Star Movement in Italy has enjoyed success, the picture is different in Spain, where the radical-left-populist party Podemos has risen to prominence alongside the radical-right populists of Vox.

In the UK, the traditional left led by Jeremy Corbyn took control of a divided Labour Party. Infighting pushed the party to the brink of implosion during a bitter leadership contest in the wake of the Brexit decision. In France, the creation of splinter groups within or around the Socialist Party, such as Arnaud Montebourg’s Projet France to the left and Emmanuel Macron’s En marche! to the centre-right, has undermined party cohesion.

Left and right parties have experienced dwindling support in recent years. But the electoral gains made by anti-establishment parties have come mostly at the expense of left parties. This is surprising, because observers initially thought the left would be able to capitalise on the global financial crisis and its dire economic consequences.

Left parties are caught between the (radicalised) demands of erstwhile constituents and the fiscal (and monetary) policy realities of a global economy fully in tune with the neoliberal policy paradigm. A critical rethink towards globalised capital markets is on the agenda for the left if it wishes to regain room to manoeuvre in formulating domestic policies and to remain a significant progressive movement.

This article was originally published at The Loop and is republished here under a Creative Commons licence