Globally, the human and economic cost of work-related incidents remains alarmingly high, with more than 2.3 million deaths and 317 million workplace accidents occurring annually. Beyond the unacceptable human costs, the International Labour Organization (ILO) estimates these incidents account for economic costs of around 4 percent of global GDP.

Despite half a century of progress in Occupational Safety and Health (OSH), the problem persists. In 2022 alone, nearly 3 million workplace accidents were recorded across the European Union, including 3,286 fatalities (0.1 percent of total accidents). These figures likely underestimate the true scale of the issue, as workplace accidents are often under-reported, particularly in informal and precarious employment where workers fear job losses for reporting injuries. Structural factors also play a significant role, with higher accident rates prevalent in countries with a strong presence of high-risk industries such as construction, manufacturing, and agriculture. Similarly, smaller businesses often face greater OSH risks due to fewer regulatory obligations and inspections, lower unionisation rates, and competitive strategies focused on labour cost reduction.

Against this backdrop, the increasing adoption of automation technologies, including robots, presents a complex picture for OSH. While offering the potential to improve working conditions, it also introduces new workplace safety risks. Although the impact of robotisation on technological unemployment has been extensively studied, its effect on OSH, particularly within Europe, remains less understood.

A recent study offers new insights into this critical area. We empirically analysed the impact of industrial robots on workplace injuries and fatalities in European manufacturing industries between 2011 and 2019, covering 18 European nations: Austria, Belgium, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Lithuania, the Netherlands, Poland, Slovakia, Spain, and Sweden. Our analysis examined both the average effect of robotisation and its variations across industries (distinguishing them by technological intensity and innovation sources) and countries (considering institutional differences such as the strength of trade unions).

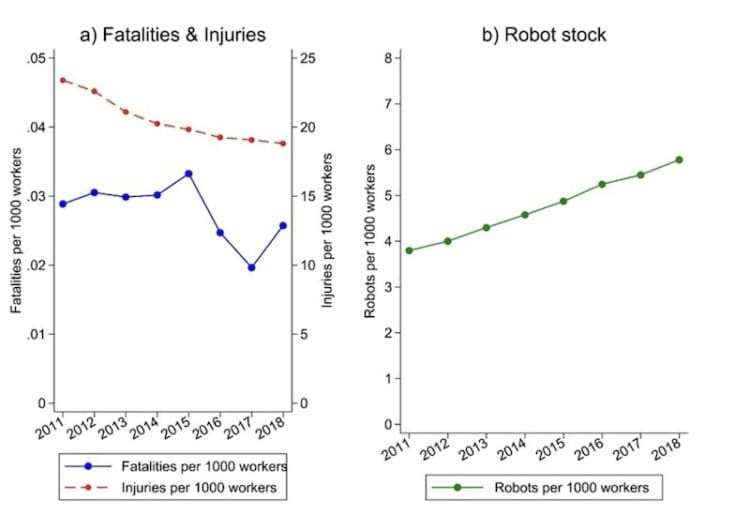

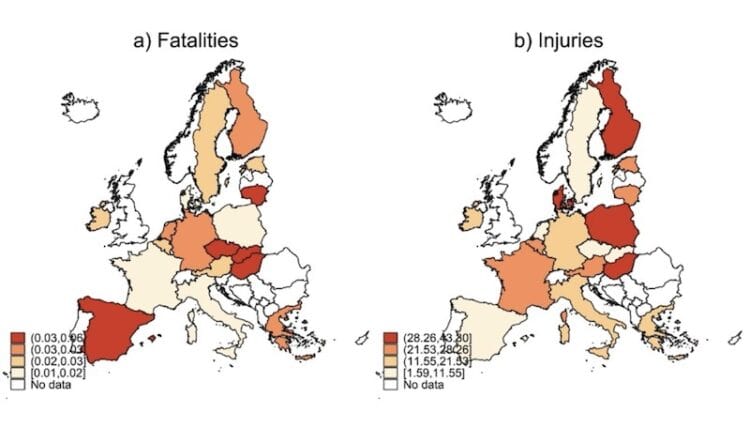

Before detailing our key findings, some descriptive trends are noteworthy. Firstly, we observed a consistent rise in robotisation alongside a decline in the incidence of workplace injuries and fatalities (Figure 1). Secondly, workplace injuries were most common in Finland, Poland, and Hungary, followed by Austria, Belgium, and France. Fatalities, conversely, were highest in Eastern European economies closely linked to German manufacturing (Hungary, Czech Republic, and Slovakia), as well as in Lithuania and Spain (Figure 2). This heterogeneity can be attributed to several factors, including the prevalence of high-risk sectors, the enforcement of workplace safety regulations, job security levels, and the extent of under-reporting. Moving beyond these observations, our analysis reveals that robotisation leads to a reduction in workplace injuries and fatalities (Table 1). This positive impact can be attributed to several factors, including the automation of hazardous tasks, the modernisation of production technology, improved ergonomics, and organisational innovations often accompanied by training programmes.

Figure 1: Evolution of workplace fatalities, injuries and robots per 1000 workers

Figure 2: Distribution of fatalities and accidents

Source: De Simone et al. (2025)

Table 1: The impact of industrial robots on workplace fatalities and injuries

| Baseline | High-tech sectors | High protection | Medium protection | |

| Fatalities | Injuries | Fatalities | Injuries | |

| Industrial robots | -0.00663*** | -0.196*** | -0.0228** | -0.996*** |

| (0.00186) | (0.0573) | (0.00920) | (0.286) |

Source: De Simone et al. (2025). Note: Table 1 summarises the estimates of the impact of industrial robots on workplace injuries and fatalities. The ‘Baseline Model’ column refers to our main aggregate estimates; the ‘High-tech sectors’ column refers to the impact of robots in ‘Science Based’ and ‘Specialised Suppliers’ sectors; the column ‘High Protection’ refers to the effect in countries with high protection (Finland, Denmark, Belgium); the column ‘Medium Protection’ reports the effect for countries with medium protection (Germany, France, Ireland, Italy, Sweden). The estimates are obtained using the instrumental variables approach. Standard errors are reported in parentheses. Asterisks indicate statistical significance: *** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.1

However, our research highlights that the impact of robotisation on OSH is not uniform and is significantly shaped by two key factors: the technological intensity of industries and the strength of industrial relations.

The reduction in occupational injuries and deaths associated with robot adoption is evident only in high-tech industries, where innovation and skilled labour are crucial for competitiveness. In contrast, robotisation does not improve OSH in low-tech industries, where a significant proportion of accidents occur and process innovation is primarily aimed at cost reduction. In such contexts, the introduction of robots may lead to an increased work pace and a reduced incentive for firms to invest in training and organisational improvements alongside automation.

Industrial relations also play a pivotal role in the relationship between robotisation and safety. In countries with strong trade unions and comprehensive worker protections (such as Finland, Denmark, and Belgium), robots contribute positively to workplace safety. A similar, albeit weaker, effect is observed in economies with “medium protection” (for example, Germany, France, Ireland, Italy, and Sweden). Conversely, in economies characterised by low unionisation, decentralised wage bargaining, and minimal unemployment support (including the Czech Republic, Greece, Lithuania, Slovakia, Estonia, Hungary, and Poland), no significant link between robot adoption and safety improvements is found.

Work-related injuries and deaths remain a significant societal challenge, despite stringent regulations aimed at prevention, controls, and sanctions. Our findings demonstrate that robotisation has the potential to enhance OSH, but this is contingent on specific conditions: deployment in industries that prioritise innovation and skills development, and within institutional frameworks that provide strong worker protections. Without these conditions, the safety benefits of automation remain uncertain.

Some might argue that robots simply reduce injuries by replacing human workers. However, research suggests otherwise. A recent meta-analysis indicates that robotisation has little to no impact on overall employment levels. The real threats to workplace safety stem from precarious work, weakened trade unions, and business models that rely on labour exploitation.

The crucial factor is not the adoption of robots itself, but the manner in which they are implemented. If robots are used primarily to intensify workloads and cut labour costs, they risk exacerbating safety concerns. However, when implemented alongside investments in training, improved working conditions, and organisational innovation, robots can be a valuable asset in enhancing workplace safety.