National measures adopted amid the energy crisis missed the opportunity to pursue social and climate goals.

Europe managed to get through the much-feared 2022-23 winter without energy shortages, power cuts and recession, showing considerable resilience albeit at a cost. According to Bruegel, between September 2021 and March 2023 European Union member states allocated €646 billion to shield consumers from rising energy costs.

Even if Europe’s fossil-fuel vulnerability could have been reduced in the past decade—not least after the Russian annexation of Crimea in 2014—such a major price shock, threatening the livelihoods of tens of millions of Europeans, required powerful action. But were these resources targeted towards those most in need and to what extent did the measures consider climate objectives?

Broad-based

National case studies explored in a recent European Trade Union Institute (ETUI) publication reveal that the measures were mostly broad-based, including subsidies, tax cuts and price controls, with price support on average making up about 60 per cent of their value. Some good practices emerged, where short-term social protection could have been aligned with longer-term ecological objectives. Yet the future is clearly in cheaper renewables.

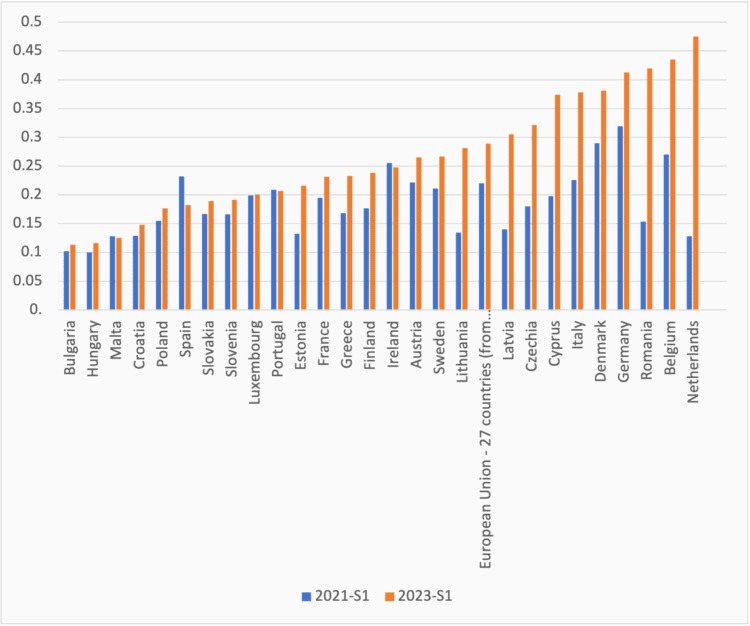

According to Eurostat, actual prices paid by households vary greatly across the EU (Figure 1). In the first half of 2023 electricity prices, including taxes and levies (though of course this not capture income-support measures) were highest in the Netherlands (€0.4750 / kilowatt hour), Belgium (0.4350/kWh), Romania (0.4199) and Germany (0.4125)—four times the prices paid by households in Hungary (0.1161) and Bulgaria (0.1137). And while some member states saw exorbitant price increases over the preceding two years (in Romania and the Netherlands 170 and 270 per cent respectively), some others registered no changes (such as Portugal and Luxembourg), while in Spain and Ireland prices actually fell.

Figure 1: electricity prices for household consumers with medium consumption, all taxes and levies included, in first semesters of 2021 and 2023 (€/KWh, yearly consumption between 2,500 and 4,999kWh)

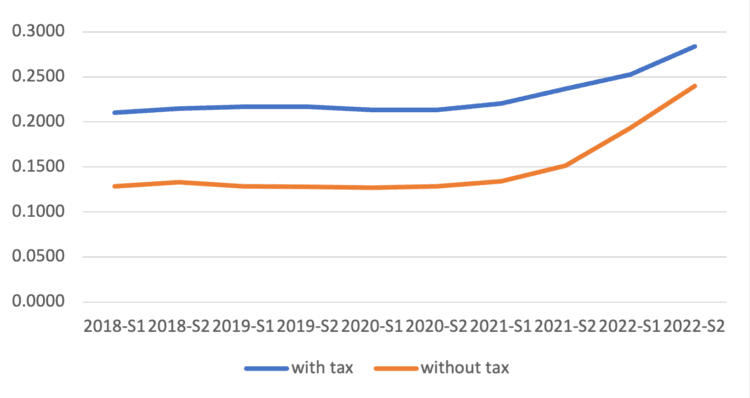

For the EU27, between the second half of 2020 and 2022 electricity prices before taxes and levies grew by 87 per cent but increased by only 32.6 per cent after all taxes and levies (Figure 2). The weight of taxes decreased substantially, from 69.2 per cent in the first half of 2019 to just 18.3 per cent in the second half of 2022. This reflects the impact of price-support measures.

Figure 2: electricity prices for EU27 household consumers, biannual data (€/kWh 2018-22), with and without taxes

Poorly targeted

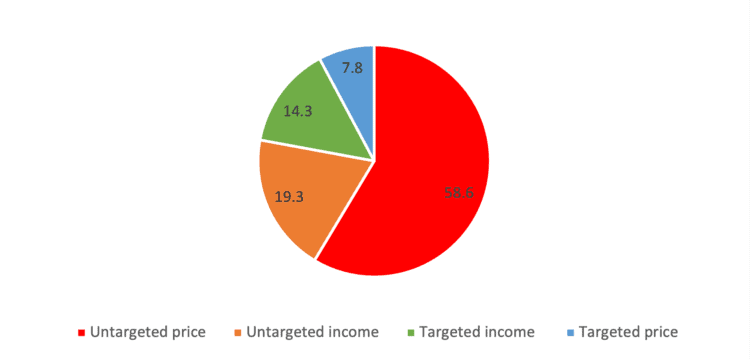

According to Bruegel, governments in the EU27 have mainly implemented non-targeted price measures (58.6 per cent of the total expended)—such as cuts to excise duties and value-added tax—followed by non-targeted income-support measures (19.2 per cent). Targeted income supports have comprised 14.3 per cent, with targeted price measures accounting for the remaining 7.8 per cent (Figure 3). So broad-based measures reaching the entire population, regardless of income or any other characteristics, have accounted for nearly 80 per cent of the total in value terms.

Figure 3: distribution of allocated and earmarked funding to shield EU27 households (Sep 2021—Jan 2023), as percentage of the total (€432 billion)

The ETUI’s case studies—Austria, France, Germany, Greece, Italy, Poland and Spain—also highlighted that, in accordance with the aggregate data for the EU27, short-term government support was poorly targeted. On average some 80 per cent of spending was on broad-based measures.

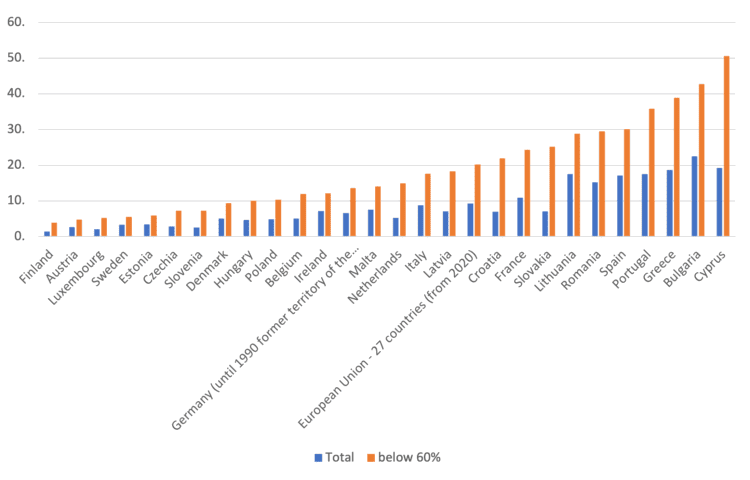

While the cost-of-living crisis may have resulted in some incremental reductions in emissions—due to the unaffordability of energy for many households—it has however aggravated inequalities with devastating social effects. According to Eurostat, energy poverty in the EU27 increased by 35 per cent between 2021 and 2022, as 9.3 per cent of the total population, or 41.5 million people, could not afford to keep their homes adequately warm (Figure 4). Furthermore, 20.2 per cent of those at risk of poverty (with below 60 per cent of national median equivalised disposable income) were unable to maintain an adequate home temperature—with much higher rates still in Greece, Bulgaria and particularly Cyprus, where half of poorer households suffered energy poverty.

Figure 4: percentage of population (blue) and of those at risk of poverty (orange) unable to keep their home warm in 2022

Climate dimension

As for the climate dimension, in 2022 demand for natural gas in the EU decreased by 13.2 per cent and the objective of the REPowerEU plan to reduce demand by 15 per cent for the period August 2022 to March 2023 was overshot (17.7 per cent). The International Energy Agency has calculated for the calendar year 2022 the main drivers of the EU’s reduction in gas demand, which fell absolutely by 55 billion cubic metres.

Power generation was the only main sector where gas demand rose from 2021 (by 2bcm), mostly due to a significant reduction of nuclear power with low water levels in rivers. Buildings—dwellings and public and commercial spaces—realised a 28bcm fall, or almost 20 per cent, mainly due to weather effects, followed by ‘behavioural changes and fuel poverty’; energy-efficiency improvements contributed just 3bcm. Demand from industry fell by 25bcm (25 per cent), with just over half coming from curtailment of production and import substitution; fuel switching accounted for 7bcm.

Only a small share of this reduction can thus be seen as sustainable. Adding the 3bcm energy-efficiency gains in buildings, maybe another 3bcm from behavioural change (certainly not from fuel poverty) and possibly the 7bcm from fuel switching in industry would still only imply a 13bcm long-term gas demand reduction—less than a quarter of the 55bcm 2021-22 total.

Macroeconomic stabilisation

The case studies revealed that governments’ short-term support measures, mobilising huge resources to shield households from the effects of the extraordinary increases in fossil energy prices, primarily sought macroeconomic stabilisation. The main political objective was to limit secondary inflationary effects and avoid recession.

While European policies under REPowerEU are directed at more medium- and long-term objectives, to limit Europe’s fossil-fuel dependency, national measures addressed the most imminent effects of the price shock. Almost €700 billion was mobilised over the two-year period the ETUI looked at, but tax reductions and price support were dominant—and these were not properly targeted.

Some countries, such as Greece and Spain, did manage to limit energy prices via subsidies and market interventions. But in each country the ETUI examined rich households benefited most in absolute terms from the support measures. And while energy-savings goals were achieved, the IEA analysis demonstrates only limited long-term effect.

While the extent of the price shock required measures that went beyond poverty reduction—lower-middle- and middle-income households were also severely affected—the resources expended on higher-income households (the fourth and fifth income quintiles) were avoidable. These funds could have provided more support for those really in need and been retained for investments badly needed for the transition away from fossil fuels.

Overall, both social and climate goals were rather sidelined. The bigger carbon footprints of higher-income groups were co-financed by scarce public resources, without incentives to reduce fossil-energy consumption. The failure to align economic and distributive goals, while gaining a climate dividend, thus represents a missed opportunity.

The complex interventions required adequately to address an economic shock of such magnitude evidently demand high-quality governance and public institutions.

Béla Galgóczi is Senior Researcher at the European Trade Union Institute and editor of Response measures to the energy crisis: policy targeting and climate trade-offs (ETUI, 2023).