The persistent decline in the membership, collective bargaining power and political influence of trade unions over the past half century has contributed to their political marginalisation. But it wasn’t always like this.

In western Europe, governments used to pay attention to unions. Unions and left-oriented political parties co-ordinated on policy and co-operated politically. The relationship between left parties and unions was mutually beneficial. Unions helped mobilise left parties’ constituencies at election time and, if elected, left governments would deliver policies that provided benefits to workers.

Much though has changed. Due to unions’ organisational decline, ties between organised labour and left parties have weakened. Some left parties pivoted to a market-friendly ‘third way’ politics to capture support from more affluent, middle-class voters. These electoral and organisational shifts left unions politically feeble, with reduced influence over their former left party allies.

Public-opinion penalties

Our recent study however suggests that unions retain an important tool for exerting political influence at the grassroots level—general strikes. Unions can use general strikes to turn public opinion against governments when they pursue policies that stray from union preferences. Our exploration of general strikes in Spain shows that the country’s Socialist Party (PSOE) governments incurred significant public-opinion penalties when they faced general strikes during their tenure. But this effect is limited: Spain’s conservative governments of the Popular Party (PP) incurred no such public-opinion costs.

General strikes are a form of protest, levied against governments in their role as policy-setters. Unions call them to protest against policies that retrench the welfare state and deregulate labour markets. Unlike work-based strikes directed against employers, unions seek support for general strikes far beyond union members. If successful, they mobilise a broad group of citizens, attract media attention, cause economic disruption and signal widespread opposition to the government’s policies. Hundreds of thousands of people may participate—indeed, an estimated seven million participated in a 1988 general strike in Spain.

How might a general strike affect public support for the government? Different hypotheses are plausible.

Given unions’ political decline, one might expect that general strikes would have no effect on public support for executives of any partisan colour. Unions might simply be too weak or politically marginalised to move public opinion.

On the other hand, by mobilising the wider public against measures that harm union members and non-members alike, general strikes could turn public opinion against governments of any stripe. Policies, such as lowering pensions, that general strikes target tend to affect core constituencies which resist cutbacks. Accordingly, any government would encounter public ire if general strikes drew attention to that.

More detrimental

Our research however suggests general strikes may be more detrimental to public support for governments of the left than those of the right. Why?

Unions typically call general strikes against austerity measures that negatively affect the rights of workers. As parties of business and small government, parties of the right champion the pro-market economic reforms general strikes often target. Such policies align with the ideological underpinnings of parties of the right and are more likely to resonate with their constituencies and therefore shelter them from a decline in public support.

In contrast, general strikes lodged against left governments may evoke a political backlash for two reasons. Left voters may feel betrayed by governments of the left which deviate from their commitments to egalitarian principles and workers’ rights. And low-income left voters may be particularly hostile when the party they voted for introduces reforms that disproportionately harm them. Because left parties historically had closer ties to unions, unions’ willingness to call a general strike against a government of the left may also signal to the public—and specifically to the left’s own constituents—the gravity of the (proposed) policies at issue.

Impact on support

We examined the impact of general strikes on public support for the government in Spain between 1986 and 2015. During that period, unions called nine general strikes and threatened another. Five of the strikes and the strike threat were against governments controlled by the mainstream-left PSOE. Four were against conservative PP governments.

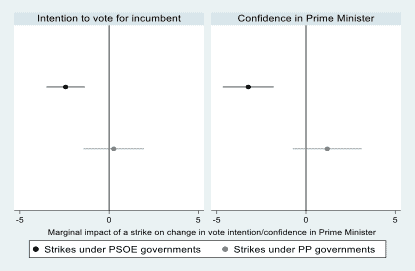

To determine whether public support for the government changed in the aftermath of a general strike, we examined responses to two survey questions regularly posed in quarterly public-opinion surveys since the late 1980s. The first asked which party the respondent would vote for if an election were held the next day. The second asked how much confidence the respondent had in the prime minister. Having access to quarterly public-opinion data allowed us to assess strikes’ potential political costs immediately after they happened (see figure).

General strikes, partisanship and shifts in public opinion

When the PSOE was in power, general strikes were associated with reduced public support for government, even after controlling for other confounding factors as well as the severity of the (proposed) reform. General strikes costs PSOE governments roughly a 2.7 per cent drop in in the proportion of respondents who claimed they would vote for the party, while they reduced confidence in left prime ministers by 4 per cent. In contrast, when the PP governed, general strikes had no effect on the public’s support for the government or their intent to vote for the party.

Important mobilisers

Left governments should thus be more concerned about general strikes than governments of the right. What does this mean for unions? On the one hand, it suggests that unions have a tool which allows them to pressurise left parties which plan or implement broad welfare cuts. At a time when unions have lost direct influence in policy making, this is important. As left parties grapple with adopting more centrist and pro-market platforms, our research indicates that unions are still important mobilisers of left voters. Left governments which ignore them may do so at their peril.

Yet, when organising general strikes, unions should also be aware that the political costs are higher for parties of the left than for those of the right. So they can erode the electoral appeal of parties whose policy agendas are closer to themselves—despite their differences.