Digital platforms have become ubiquitous in society, reshaping how we access information, connect with others, and conduct transactions. Digital platforms are now widely used for social interaction and to perform common activities such as looking for housing, purchasing and exchanging goods and services, or consuming audiovisual material and media. Like other aspects of society and the economy, the use of digital platforms is spreading quickly in workplaces across all kinds of sectors. These digital tools are increasingly used to coordinate and manage work-related interactions, leading to a “platformisation” of regular work.

The growing use of data-driven management techniques, such as digital monitoring and algorithmic management, is a key feature of this platformisation of work. While early forms of these practices emerged with the first wave of digitalisation decades ago, the more recent surge of the gig economy has relied on significantly more sophisticated forms of digital monitoring and algorithmic management.

We now see that these practices spread beyond the boundary of platform work, penetrating all kinds of workplaces across most sectors and countries. This means that digital devices and software algorithms are becoming increasingly used not merely as work tools, but as mechanisms of coordination and managerial control. We think that this can represent a fundamental reshaping of how work is organised, managed and controlled.

The growing platformisation of work raises questions about workplace power dynamics and worker monitoring and surveillance, with potentially critical implications for job quality and individual autonomy and agency. However, it is an emerging phenomenon with still unclear boundaries and uncertain implications. On the one hand, platformisation can improve work organisation, streamline work processes, and generate efficiency gains. On the other, it can lead to work intensification and digital bureaucratisation. Recent case studies highlight the dual nature of this phenomenon, stressing how it can often mitigate physical occupational health and safety risks for workers, but also exacerbate psychosocial risks.

As part of our research programme on the changing nature of work in the EU, in 2024-2025 we conducted a worker survey on the Impact of Algorithmic Management and Artificial Intelligence in the Workplace (AIM-WORK), which includes responses from 70,316 individuals in all EU member states. As outlined in a recently published report, thanks to this large new dataset we can now measure platformisation through three distinct but closely related phenomena.

First, the increasing use of digital tools at work, including artificial intelligence (AI), represents the material base for the development of data-driven managerial practices. Second, the digital monitoring of work entails the use of data collected through digital devices about the work process and workers themselves. Third, the algorithmic management of work is the use of digital technologies, which may be powered by AI or not, to automate workforce management and coordination functions.

The digital workplace revolution

The first key dimension of platformisation, its key enabling factor, is the use of digital tools at work. AIM-WORK data shows that digital tool usage is pervasive in the European context: more than 90 per cent of workers currently use digital tools for work-related purposes. However, significant variations exist across countries and occupations, with northern and central European countries showing higher adoption rates. While nearly all highly educated workers use digital tools at work, 50 per cent of those with low education do not use any, suggesting a persistent digital divide within the workplace.

Importantly, our data reveals a rapid deployment of AI tools at work: a high proportion of EU workers (30 per cent) have used AI-powered tools for work at least once in the last 12 months. This concerns particularly AI chatbots powered by large language models (LLMs), suggesting a proactive, worker-led usage, most likely through their personal devices, to get targeted support for work-related tasks such as writing and translation.

The second key dimension of platformisation is the digital monitoring of work, and AIM-WORK data reveals that it is increasingly common in the EU. Digital tools are mostly used for the monitoring of working time—37 per cent of EU workers are digitally monitored for working hours and 36 per cent for entry and exit of work. “Physical monitoring”, or the monitoring of the physical location of workers, is less common but not at all marginal: for instance, 14 per cent of EU workers are physically monitored through cameras. “Activity monitoring”, or the monitoring through digital tools of worker activities, is also relevant: 12 per cent of EU workers report that their calls or emails are monitored by their employer. Some of these forms of digital monitoring can be quite intrusive, and our data shows that they are quite common in some sectors and countries. Prevalence of digital monitoring, including the most intrusive forms, is highest in some member states of central and eastern Europe.

The third key dimension of platformisation is the algorithmic management of work—less common than digital monitoring, but not at all insignificant. In fact, some forms of algorithmic management are rather frequent. For example, our survey results indicate that 24 per cent of EU workers have their working time allocated automatically via digital devices. This form of automated working time allocation is part of what we refer to as “algorithmic direction”, often paired with algorithms that determine workflow or task prioritisation.

On the other hand, “algorithmic evaluation”, where performance is assessed and rewarded or penalised automatically, is also present in European workplaces, albeit to a lesser extent. All in all, algorithmic management is most frequent in Spain, Poland, Ireland, and Romania, where most types of algorithmic management are around or above the EU average.

Six categories of digital control

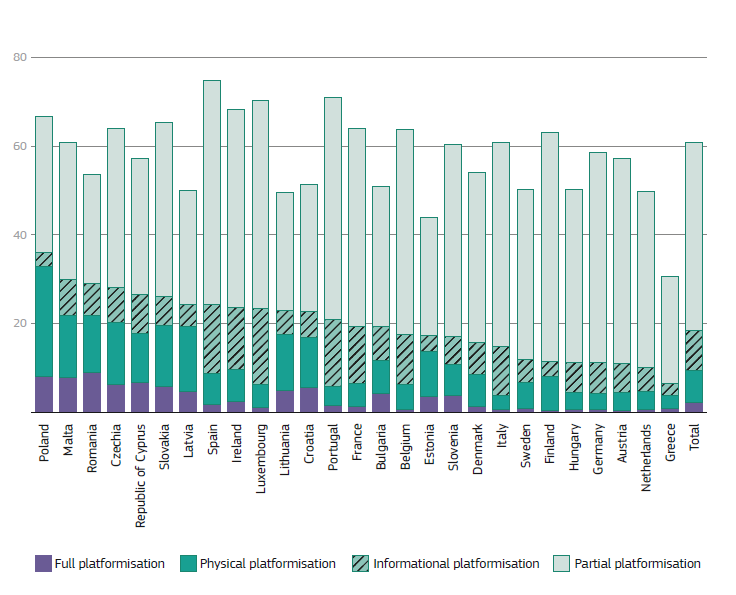

Building on the new data, we propose a classification of workers based on the combination of digital tool usage and exposure to different types of digital monitoring and algorithmic management. Specifically, we put forward six categories of workers that reveal the spectrum of platformisation across Europe.

- 6 per cent of EU workers do not use digital tools and are foreign to any form of platformisation.

- 33 per cent of workers use digital tools but are not subject to any form of digital monitoring or algorithmic management.

- 42 per cent fall under partial (or weak) platformisation. This means that they are exposed to at least one form of digital monitoring and one form of algorithmic management, but not more than one of each.

- 9 per cent of workers experience informational platformisation, that is, they are simultaneously subject to activity monitoring and algorithmic evaluation. This is most frequent in the financial and insurance sectors.

- 7 per cent face physical platformisation, a combination of physical monitoring and algorithmic direction. This type of platformisation is common in sectors such as mining, transportation and logistics.

- Finally, 2 per cent of EU workers are fully platformised. This means that they are simultaneously subject to all forms of digital monitoring and algorithmic management.

The distribution of these categories varies dramatically across Europe. Overall, the prevalence of platformisation is generally high in central and eastern Europe, and low in western and northern Europe. Only a handful of countries—particularly Spain, Portugal, France, Belgium, and Ireland—have intermediate values of platformisation.

The platformisation of work in the EU, Source: Gonzalez-Vazquez et al. 2025

Our analysis suggests that partial forms of platformisation as well as what we called “informational platformisation” (typical of office work) do not have significant negative consequences for workers. On the other hand, the categories of “full” and “physical platformisation” (typical of manual work activities and combining physical monitoring and algorithmic direction) are associated with increased stress and diminished autonomy and flexibility.

The AIM-WORK data provides an updated snapshot of the way the digital revolution continues to reshape the European world of work. Contrary to the prevailing narrative warning about job losses due to automation and generative AI, we believe that the most consequential impact of the digitalisation of the workplace concerns how work is organised, coordinated, and controlled. Some of the combined forms of digital monitoring and algorithmic management—in particular, the categories of “full” and “physical” platformisation—should be carefully considered in terms of their potentially negative implications for working conditions. How we confront these challenges will ultimately determine whether the digital workplace becomes a site of empowerment or one of ever-tighter control.