When OECD Social Ministers gather in Paris this Valentine’s Day, they will confront a challenge that transcends political divides: ensuring sustainable social protection in an era of unprecedented demographic change. While these ministers represent governments of differing political traditions and compositions, they share two pressing realities.

First, recent events have reinforced the vital role of robust social protection systems. The pandemic, the inflation shock and the ongoing cost-of-living crisis have underscored that social protection is not merely a safety net but a fundamental pillar of society—essential for well-being and inclusive economic growth. Strong social protection systems provide security when it is needed, acting as redistributors and automatic stabilisers in economic downturns. Without income support measures such as sick pay, unemployment benefits and short-time work programmes, the severity of economic crises—such as that of the pandemic years from 2020 to 2022—would have been far greater, and poverty and inequality levels even higher.

Governments of all political stripes recognise this, which may explain why administrations traditionally opposed to social spending have introduced enhancements to benefit levels or extended temporary increases.

Secondly, Social Ministers are grappling with a common and increasingly urgent challenge: demographic change. Or at least they should be—because the figures are alarming.

Birth rates are falling well below the so-called replacement rate of 2.1 in every OECD country except Israel, and in several major European economies, including Germany, Italy and Spain, they are significantly lower than the OECD average of 1.5. Just six decades ago, the figure stood at 3.3. At the same time, average life expectancy has risen dramatically, leading to a surge in the number of retirees. In 2024, there were 33 people aged 65 and over for every 100 working-age individuals in the OECD. This ratio is projected to almost double within four decades, creating substantial gaps in the financing of social protection, particularly pensions.

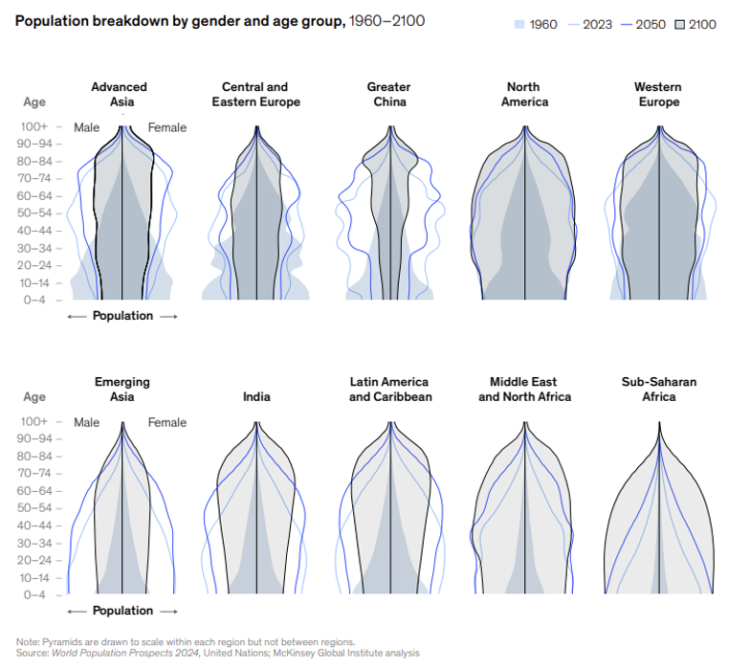

With falling birth rates, ageing populations and shrinking workforces, OECD states stand on the brink of a demographic crisis. The scale of this shift is transforming population structures. While corporate consultancies such as McKinsey frame the issue in terms of economic impact—warning of a potential decline of ten thousand dollars per capita in Western Europe over the next quarter-century—the real challenge is fundamentally social. Their evocative term, “population obelisks,” captures the shift away from traditional pyramid-shaped demographic distributions. But the central question remains: how can governments maintain social solidarity in the face of these changes?

The demographic crisis demands a fundamental rethinking of how social protection is financed. Many governments have resorted to raising retirement ages or cutting benefits, but evidence suggests that these measures only deepen inequality without addressing the underlying problem. A broader set of policy options is needed—ones that secure sustainable social protection financing while promoting greater equality.

The current primary source of funding for social protection—labour income—is increasingly under strain. Workforces are shrinking, precarious employment is rising, and the labour income share is declining. The resource base must be broadened.

Several OECD governments have attempted to address the issue by raising retirement ages. However, requiring all workers to remain in employment for longer is an inequitable approach to strengthening social protection financing. In many countries, those on lower incomes have seen little improvement in life expectancy, or even declines. Raising the retirement age means that lower-income workers effectively subsidise additional years of pensions for their wealthier peers, whom they may not live long enough to join in retirement.

Some governments have pinned their hopes on restricting social protection spending by reducing benefit levels or durations, imposing additional conditions and limiting access to income support. This strategy is equally short-sighted. Studies of such policies point to severe long-term consequences, including diminished well-being, rising poverty and increased crime rates.

The trade union movement—represented at the Ministerial meeting by the Trade Union Advisory Committee (TUAC) to the OECD—has put forward a more comprehensive approach to addressing the demographic crisis. Rather than relying on blunt instruments such as raising retirement ages or cutting benefits, TUAC proposes three interconnected strategies that could reinforce social protection while strengthening social cohesion.

First, governments should introduce higher, more comprehensive and progressive taxes on wealth, profits and capital, while taking decisive action against tax evasion and avoidance. Given the scale of global tax evasion, national legislation alone is insufficient. International cooperation is essential to ensure that capital contributes its fair share to social protection financing, alleviating record levels of inequality in the process.

Second, fiscal and monetary policies should be deployed to boost aggregate demand and drive employment growth. Governments must prioritise labour market integration by improving opportunities for women, migrants, people with disabilities, those not in education, employment or training, and other groups at greater risk of exclusion. Reducing unemployment, precarious work and informality not only strengthens social protection financing but also enhances overall well-being and social cohesion.

Third, instead of raising retirement ages, governments should enable those who wish to continue working to do so by improving job quality and working conditions. Enhancing job security can reduce sick leave, workplace accidents and early retirement due to ill health, keeping more people in the workforce for longer. The ability to extend working lives also depends on facilitating job mobility and career transitions through investment in lifelong learning programmes.

The demographic crisis facing OECD countries is not just a question of numbers—it is about the kind of society we wish to build. As Social Ministers gather in Paris to debate pension reform and social protection financing, a fairer path is available. Rather than forcing workers to bear the burden through longer working lives and diminished benefits, this meeting presents an opportunity to chart a different course. By taxing capital more effectively, expanding employment and improving job quality, OECD governments can build social protection systems that are not only financially sustainable but also socially just. The course of action is clear; what is needed now is the political will to pursue it.