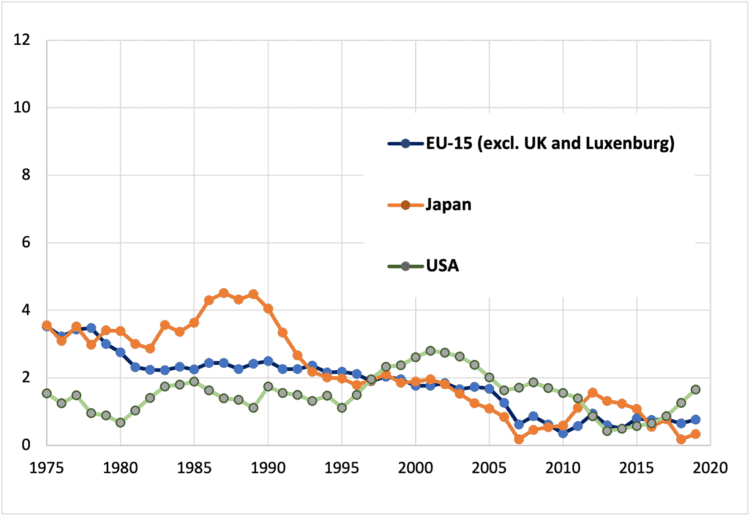

In key member states of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, productivity growth has slowed significantly since around 2004-05 (Figure 1). This is essentially due to two factors.

First, the contribution of information and communication technology to aggregate productivity growth in major OECD countries strongly declined from 2004 onwards, after a ten-year ICT boom in the United States. Secondly, ‘supply-side’ labour market reforms prove harmful to innovation, especially where innovation relies on a highly cumulative knowledge base. There are many arguments on this but, most importantly, structural reforms aimed at easier firing and higher turnover of staff are detrimental to the accumulation of (tacit) knowledge from experience.

Figure 1: growth (%) of gross domestic product per hour worked, 1975-2019 (five-year moving averages)

Slower productivity growth means slower growth of the cake that can be distributed between capital, labour and government, and this makes it harder to solve distributional conflicts or, for example, to finance the European Green Deal. Intensified distributional struggles can in turn increase inflation.

Such struggles can be exacerbated by a side-effect of low productivity growth—labour-intensive economic growth. An economy can only grow with more working hours or more productive working hours. With failing productivity growth, recourse to higher labour input is the only alternative to feed economic growth. But, sooner or later, labour-intensive growth will make labour markets tighter.

From the viewpoint of supply-side economics, there is then a risk that unemployment will become far too low—and this where there is little (extra) to be distributed due to the productivity crisis. The coincidence of tiny growth of the cake to be distributed with more assertive trade unions in tighter labour markets can increase inflationary pressure. This will make supply-siders call for some new ‘Volcker shock’—in 1979, amid high inflation, the then chair of the US Federal Reserve, Paul Volcker, hiked its interest rate to 20 per cent and precipitated recession—raising unemployment and thus disciplining workers.

Germany versus the US

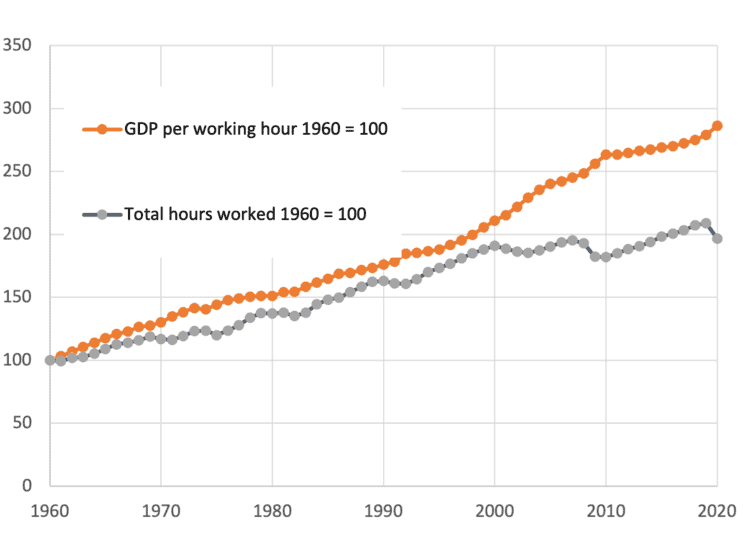

The relationship between low productivity growth and highly labour-intensive economic growth can be illustrated by comparing Germany and the US, respectively ‘co-ordinated’ and ‘liberalised’ market economies in the varieties-of-capitalism schema of Hall and Soskice. Figure 1 shows that, between 1975 and 1995, US productivity growth was lower and hence more labour-intensive (Figure 2) than in the European Union and Japan.

This can be explained by the US taking a lead in implementing supply-side labour-market reforms. These were followed by weaker innovation performance in its old economy, thus creating the ‘rust belt’. In contrast, there was up to 2005 still a highly productivity-driven and therefore relatively labour-extensive growth in Germany (Figure 3).

All values in Figures 2 and 3 are normalised to 1960 = 100. On that benchmark, productivity in Germany increases to 450 in 2020, while in the US it reaches just 300 during the same period. Working hours provide the mirror image: between 1960 and 2020 US growth required a doubling of working hours (100 to 200), while in Germany they fell (100 to 77).

Yet the ‘booming US jobs machine’ was to serve as a major selling-point for supply-side economics. Its advocates repeatedly referred to a ‘sclerotic’ Europe creating too few jobs, purportedly because of ‘rigid’ labour markets and ‘over-mighty’ trade unions. In fact, economic growth in Germany was more intelligent: Germans produced more with less work, while Americans had to sacrifice lots of leisure time to bring about growth.

Figure 2: labour-intensive and poorly productive growth in the US, 1960-2020 (1960 = 100)

Figure 3: productivity-driven and labour-extensive growth in Germany, 1960-2020 (1960 = 100)

This was how Germany avoided high unemployment, despite total working hours falling from 1960 while labour supply from women and migrant workers increased substantially. Average working hours per employee per year happened to be equal in the US and Germany in 1975—1,813. Twenty years later, however, while the US figure remained almost unchanged (1,817 hours), the German tally had fallen to 1,531. By 2020, the gap had widened further—1,751 hours in the US versus 1,324 in Germany.

Unacceptably low unemployment

One of the most important victories of the right in recent decades has been that centre-left parties have spent more time discussing reforming labour markets and moderating wage claims than achieving a productivity-driven (and labour-extensive) growth path, complemented by adequate reductions of standard working hours.

With Germany experiencing only modest productivity growth since the 2002-05 labour-market reforms under a social-democrat-led government, two things can be expected to happen. First, there is less (extra) to be distributed each year, so someone—capital, labour and/or government—has to sacrifice claims for extra revenues. The most likely outcome is wage stagnation and greater clamour for austerity.

Secondly, however, the bargaining position of labour improves as a result of more labour-intensive growth and falling unemployment. More assertive trade unions will then most likely face a supply-side campaign that the European Central Bank must hike interest rates, to ‘do something’ about unacceptably low unemployment supposedly causing inflationary wage claims. Yesterday the bank announced a 0.5 per cent increase, with more action promised as early as September.

Obviously, this time, a new Volcker shock for disciplining workers will not need a 20 per cent interest rate. A few additional percentage points are probably sufficient in today’s overheated markets to achieve a crash in the value of properties, stocks and bonds, not to speak of crypto-currencies and other junk. Historical experience shows that crashes in financial markets—and certainly in several markets simultaneously—can cause longer-lasting recessions.

Default assumption

For more than 150 years, economists have made the default assumption that innovation is ‘exogenous’. It’s a comfortable assumption: if, whether neoclassical or Keynesian, they know so little about innovation, then it probably isn’t that important.

Yet because of their ignorance about innovation, supply-siders have no idea that (the diffusion of) innovation is suffering from their structural reforms—and that this ultimately leads to lower productivity growth and a tight labour market, in which wage demands can easily exceed (low) productivity growth. In this situation, they know no better than to strangle the business cycle through interest-rate hikes, hoping that high unemployment will eventually make wages fall and thus render inflation manageable.

Yet falling wages again reduce productivity growth, which narrows the scope for distribution even further, thus creating additional inflationary pressures and even tighter public budgets, with calls for renewed austerity measures. In the end, the Volcker shock becomes an enduring, painful exercise.

Fortunately, there are alternatives. First, supply-side structural reforms of labour markets detrimental to innovation—especially innovation reliant on cumulative knowledge—should be rolled back. Secondly, tighter labour markets should be allowed to do their job: if demand is greater than supply, prices (in this case wages) need to go up. This is how markets are supposed to work.

Greater wage-cost pressure will favour a turn to a more productivity-driven (and less labour-intensive) growth model, as in Germany before 2005, via quicker diffusion of advanced process technology raising productivity growth. Bigger productivity gains, in turn, will increase the cake that can be distributed, which can relax inflationary pressures as well as austerity demands.

Alfred Kleinknecht is emeritus professor of economics at TU Delft and visiting professor in the School of Economics, Kwansei Gakuin University, Nishinomiya, Japan.