The long-term outcome of the bloody Russian invasion of Ukraine will depend on hard power (coercion, tanks and rockets versus Molotov cocktails and rifles), as well as soft (winning hearts and minds at home and abroad). In turn, soft power depends on cultural attitudes and information streams flowing through legacy airwaves, digital platforms and personal networks.

Surveys conducted immediately before and after the onset of the invasion on February 24th report that the majority of ordinary Russians expressed support for the war and for the president, Vladimir Putin. Overall, across the series of initial polls, a ‘silent majority’—about 60 per cent of Russian respondents—indicated that they endorsed the ‘special military operation’ in Ukraine.

But are these results reliable indicators of Russian views prior to the invasion? In February and early March, did most ordinary Russians actually sympathise with Putin’s decision to declare war?

History will ultimately decide how much of the blame for initiating the bloodshed rests on Putin alone, as well as his Kremlin acolytes, and how much responsibility rests with the tacit acceptance of ordinary Russians. It is important to determine this issue morally, to assess culpability for the conflict, and legally, to prosecute potential war crimes. Understanding Putin’s soft power can also provide insights into the long-term consequences of the conflict for his leadership and for the future of both countries.

The early polls can be treated, as with surveys elsewhere, as genuine signals of Russian public opinion. After all, cultural attitudes of nationalism, patriotism and support for strong leaders remain powerful forces in the world. Many Russian citizens may have no idea of what is happening in their name and judge only on pictures from Russian state television.

State propaganda and misinformation about Ukraine ‘shooting its own citizens in the Donbas region’ started back in 2014 and since then have been increasing in intensity and volume. Even if many ordinary Russians are badly misinformed, however, the early polls may still capture authentic attitudes reflecting a silent majority at home supporting Putin’s actions and thus represent the social construction of reality in modern Russia. At the same time, there are several potential reasons why the results from the early polls should be treated with great caution—or perhaps even discounted as meaningful.

State control and biased pollsters?

One argument suggests that many Russian market-research organisations, such as VCIOM and FOM, are state-controlled and far from equivalent to reputable, independent pollsters such as Gallup, IPSOS or YouGov. This could indeed be an issue. Yet the results of several early surveys from various polling agencies, while far from identical, appear to suggest that, in the initial phase at least, the invasion was supported by the majority of the Russian public.

The most reputable public-opinion data available in Russia are from the Levada Center, a non-governmental research organisation conducting regular surveys since 1988. Levada surveys on February 17th-21st found that the majority of respondents (52 per cent) felt negatively towards Ukraine. Most (60 per cent) blamed the United States and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization for the escalation of tensions in eastern Ukraine, while only 4 per cent blamed Russia. Their polls suggest that net public approval of Putin had surged by about 13 percentage points since December, a rally-round-the-flag effect, with almost three-quarters (71 per cent) expressing approval of his leadership by February.

These were not isolated results: even stronger sentiments were recorded in the pre-war poll conducted on February 7th-15th for CNN in Russia by a British agency, Savanta ComRes, where half (50 per cent) agreed that ‘it would be right for Moscow to use military force to prevent Kyiv from joining NATO’. Two-thirds of Russians (64 per cent) in the poll said that Russians and Ukrainians are ‘one people’, a position taught in the Soviet era and a view which Putin has been pushing, compared with just 28 per cent of Ukrainians.

In its survey of February 25th-27th, VCIOM reported strong support for the ‘special military operation’ in Ukraine, with two-thirds (68 per cent) in favour, around one quarter (22 per cent) against, and only 10 per cent unable to provide an answer. FOM showed that 65 per cent of respondents supported the ‘launch of Russia’s special military operation’ in a February 25th-27th survey. A private survey agency, Russian Field, reported that 59 per cent of respondents supported ‘Russian military action in Ukraine’ in polls conducted from February 26th to 28th. Finally, the Washington Post also reported that a poll conducted a week into the assault by a consortium of researchers confirmed that most Russians (58 per cent) approved of the invasion, while only a quarter (23 per cent) opposed it.

Clearly not all Russians supported the war before and at the outbreak of the conflict but, overall, about 60 per cent did, according to different measures by different polls. If a common bias were to influence the results from all the private and state-controlled survey organisations, though, then it could be impossible to establish any systematic and genuine evidence of Russian public opinion, for or against the war.

Self-censorship and response bias

A potential reason for any bias could be self-censorship by respondents, generating inauthentic replies and response bias. Citizens living in repressive states may avoid expressing dissenting views in survey interviews involving sensitive issues, to avoid the risk of their opinions being reported to state authorities.

This claim may be valid. Even in western countries it is often difficult to establish truthful accounts in surveys where respondents may be reluctant to express their views on direct question about certain moral topics, for fear of social sanction—such as those concerning risky sexual behaviour, the overt expression of racism, sexism and homophobia or even turning out to vote. The difficulty is compounded when monitoring attitudes towards the authorities in repressive states lacking human rights and freedom of expression.

Survey-list experiments are designed to detect hidden biases. Some studies using this technique to measure Putin’s popularity found only modest response biases. Others, such as studies in China, detect however more substantial practices of self-censorship. Our own (forthcoming) list experiments in the World Values Survey suggest varied degrees of bias in people expressing support for their own leader across diverse authoritarian states such as Ethiopia, Nicaragua and Iran. Yet even if some Russians do self-censor, it remains doubtful if the most generous estimates of response bias could reverse the balance of public opinion reported in many of the early polls favouring the use of military force in Ukraine.

Another view suggests that a more reliable guide to ‘genuine’ Russian attitudes may the exodus of dissenters and the outbreak of mass street protests and civil disobedience. Human-rights groups report widespread anti-war protests in cities across the country, despite harsh police crackdowns and the risks of serious injury and imprisonment. Thousands of anti-war demonstrators have been arrested to date. Thousands more Russians have fled abroad.

But the claim that dissenters express the underlying genuine views of most ordinary Russians may reflect western hopes more than reality. Activists normally constitute an atypical cross-section of the general population in most countries, even in liberal democracies without constraints on freedom to demonstrate peacefully. The ‘silent majority’ are unlikely to engage.

Hypothetical questions and fluid opinion

Further doubts about the reliability of Russian polls may arise from responses to hypothetical questions where public opinion remains fluid and vague. This process can generate ‘top of the head’ answers ticking the interviewer’s boxes, where most people have however probably not given the matter much thought.

The early polls are just that. Attitudes are likely to become firmer over time, although the direction of any response depends on cultural values and the attribution of blame. Whether Russian attitudes persist as events unfold remains an open question—particularly as soldiers come home in body-bags, economic sanctions bite even harder, personal messages flow across borders and the strength of Ukrainian resistance becomes evident.

Dramatic shifts in public and elite opinion have occurred around the world following the historic events in Ukraine and blanket media coverage: the heart-rending images of refugees, cities flattened to rubble, speeches by the president, Volodymyr Zelensky, and moving interviews with ordinary Ukrainians. Their impact is demonstrated by dramatic policy changes on funding the military and the importance of security in NATO member states (especially Germany) and the European Union.

But the impact of war coverage on domestic opinion in Russia is conditioned by cultural attitudes—especially fatalism towards the authorities and the powerful force of nationalism—and requires the effort to gain access to the available information. Even if opposition gradually grows, however, subsequent polls cannot be read backwards as an indication of Russian opinions at the time of the invasion.

Media censorship, propaganda and disinformation

The final and most plausible explanation for the initial polls reporting Russian support of the war lies in the manipulation of public opinion through state control of communication channels and the widespread use of censorship, propaganda and disinformation at home and abroad. Reports suggest that Russians have dismissed the word of friends and relatives living in Ukraine with first-hand experience of the war. Instead, Russians suggest that the Ukrainian army attacked its own population in ‘false flag’ operations to blame Putin, following the orders of a government consisting of ‘neo-fascists’, ‘nationalists’ and ‘drug addicts’.

This ‘official’ account of events, formulated by Putin’s regime, has been widely disseminated via state television. Information shared in Ukrainian or international media is labelled as ‘fake’, while graphic images of flattened cities are described as ‘manipulated’.

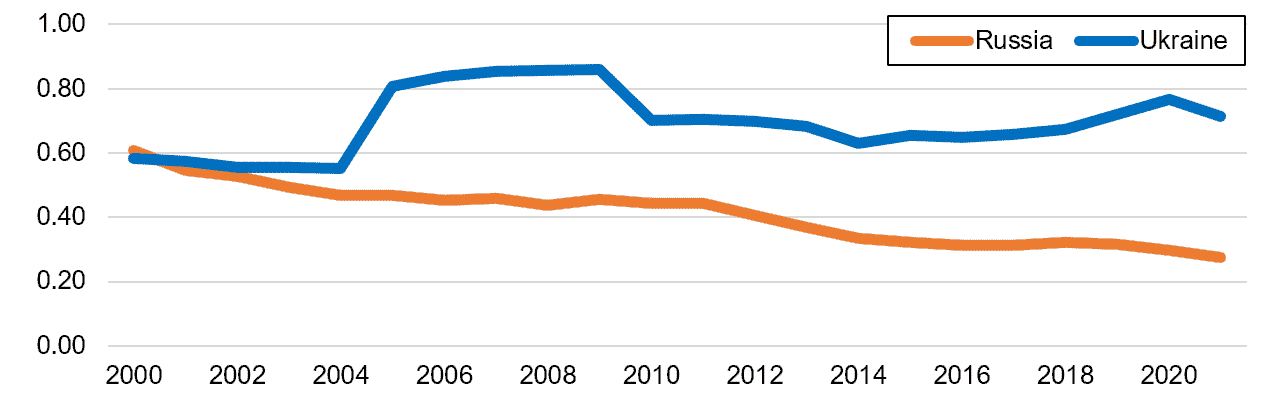

State control of the media has grown for many years under Putin—a process sharply accelerated in recent weeks. The Varieties of Democracy project publishes an index of freedom of expression and alternative sources of information, which reflects how far government respects media freedom. Since 2000, the index has steadily plummeted in Russia, while becoming significantly higher in Ukraine (Figure 1).

The latest crackdown has greatly tightened Putin’s censorship: a new law means that journalists providing military information deemed false by the state can face sentences of up to 15 years. Many international news corporations, such as CNN and the BBC, have suspended operations and remaining independent media outlets in Russia, such as the newspaper Novaya Gazeta and the independent TV channel Dozhd, have been shuttered. Even before these events, in 2021 Russia ranked 150th out of 180 countries worldwide on press freedom, according to Reporters without Borders.

Figure 1: index of freedom of expression and alternative sources of information—scores for Russia and Ukraine

But modern, well-educated, middle-class Russians, particularly technologically adept younger generations, have not yet become as isolated and rigidly controlled as populations in Turkmenistan, Eritrea and North Korea. To counter censorship, Russians can still use virtual private networks—demand for which has surged—to gain access to international news.

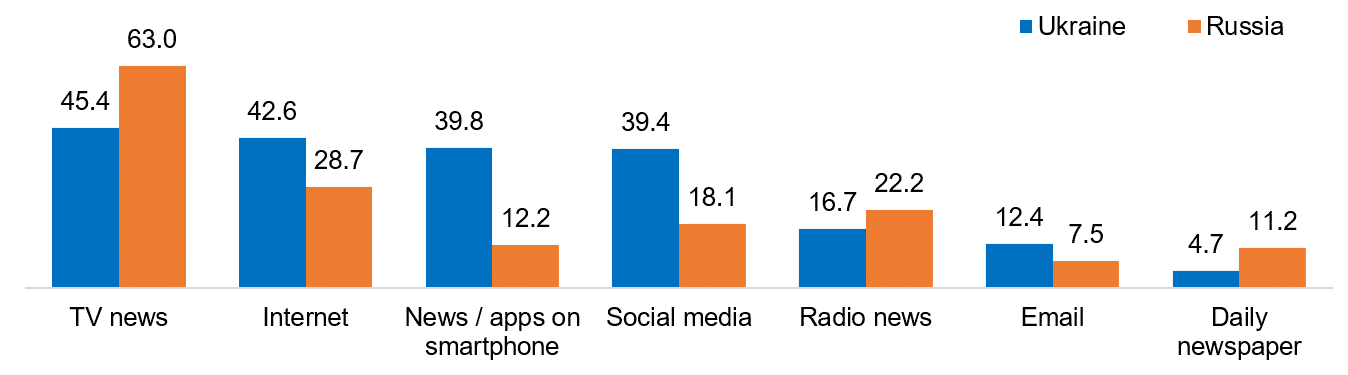

Yet that access takes effort and technical know-how. Evidence from the latest World Values Survey, conducted in Russia in 2018 and Ukraine in 2020, indicates that two-thirds of Russians still use television as their primary source of daily news and only a minority rely on the internet. By contrast, in Ukraine, an almost equal number now use the internet as television news (Figure 2).

Figure 2: information sources used on a daily basis to learn what is going on in your country

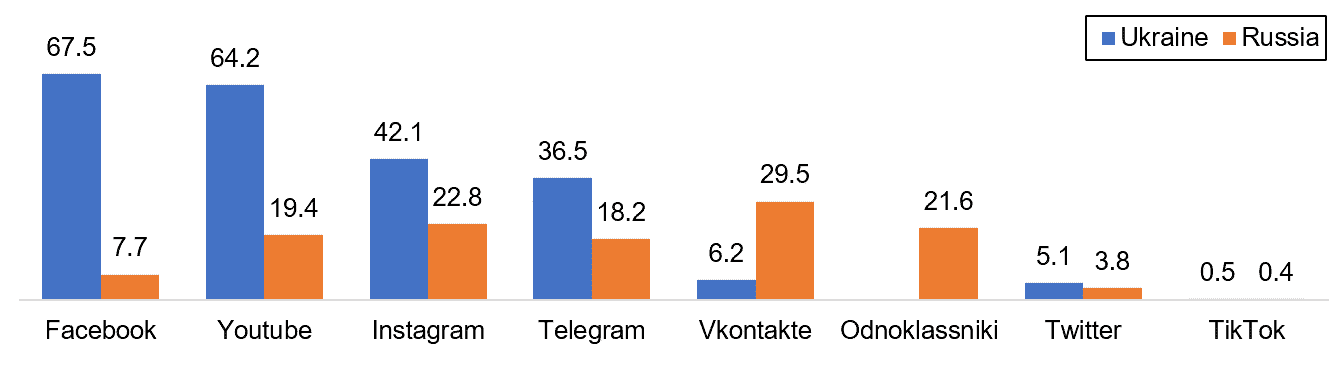

Among Russian internet users, even before the recent state bans on international platforms such as Facebook and Twitter, many relied on domestic sources. Wave 3 of the Eurasia Barometer, conducted in November 2021, found that the Russian ‘social media’ platforms VKontakte and Odnoklassniki were widely used at home. Ukrainians used western/international ‘social media’ far more than did Russians (Figure 3).

Figure 3: use of ‘social media’ in Ukraine and Russia

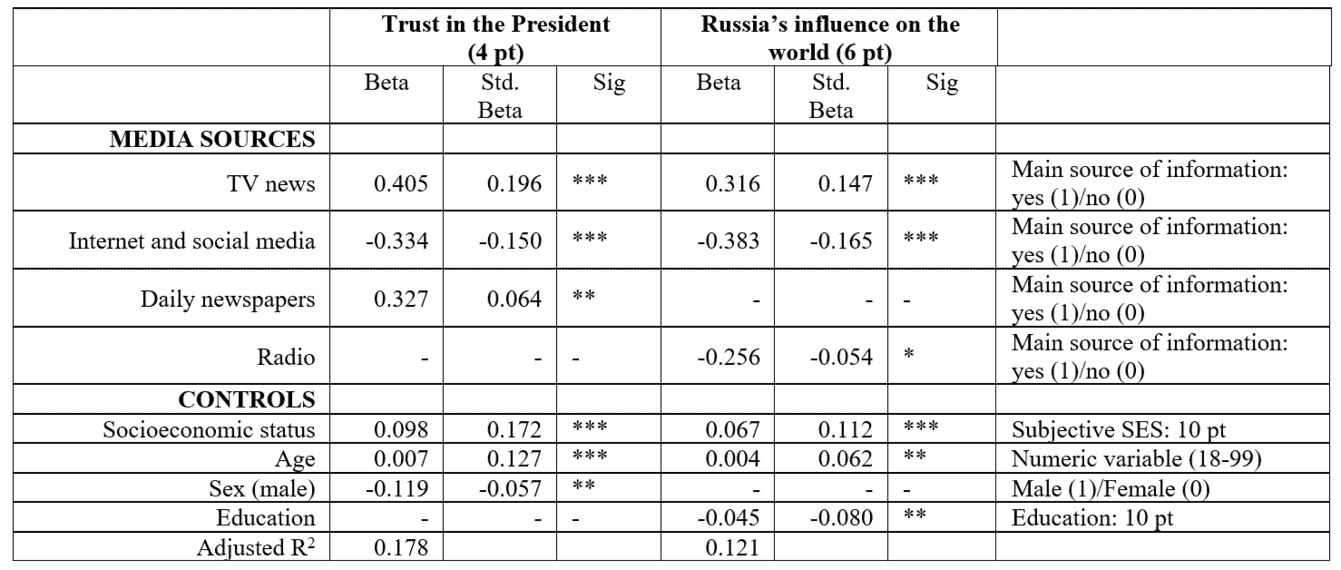

Most importantly, we find that use of television and the internet predict Russian political attitudes, in divergent directions (Table 1). The Eurasia Barometer survey, founded in 1989, provides one of the most authoritative and reliable sources of data. The survey monitors trust in the president and assessments of Russia’s influence on the world. In general, in November 2021 the role of Russia in the world was regarded positively by about 81 per cent of respondents in Russia and only 14 per cent in Ukraine. Trust in their own leader reached 59 per cent in Russia and just 35 per cent in Ukraine.

Table 1: media sources and political perceptions in Russia

After controlling for standard background characteristics, we found watching television news positively linked in Russia with trust in Putin and positive perceptions of Russia’s role in the world. By contrast, using the internet and ‘social media’ in Russia produces the reverse pattern, with less trust in Putin and more negative views of Russia’s influence. With radio and newspaper use the patterns are more mixed. This process is likely to work as a ‘virtuous circle’: both self-selection of news sources and the effects of exposure would enhance the correlation between media use and political attitudes.

The impacts of online resources and ‘social media’ also diverge sharply in the two countries. In Russia, state propaganda on television and censorship of independent ‘social media’ have isolated the country and successfully brainwashed numerous citizens obediently to repeat narratives ‘as heard on TV’. It requires an effort for Russians to obtain and compare information from various sources. It requires far more sacrifice for ordinary citizens to stand up and express any public dissent towards the authorities.

It is easiest for us all to blame Putin, his Kremlin acolytes and the security forces for the carnage, rubble and bloodshed in this war of choice. But even passive public support expressed in polls for Putin’s decision to invade Ukraine means that, as with Adolf Hitler’s ‘willing executioners’, some broader culpability for the subsequent catastrophe in both countries is shared among the silent majority of ordinary citizens in Russian society.

In Ukraine, by contrast, the flood of real-time videos across Facebook, Telegram, Twitter, WhatsApp and other ‘social media’ networks has become a major source of information about the cruelty of Putin’s ruthless actions towards the country and exposed Moscow’s propaganda, at home and abroad. The direct voices of Ukrainian people—not least through interviews with numerous fluent English-speaking refugees and official spokespersons—have been heard all over the world.

All Ukrainian settlements share constantly-updated live information through several Telegram channels and WhatsApp groups, about the shelling and fire alarms, gains and losses among Ukrainian forces and the civilian population, schedules for pharmacies and supermarkets, available humanitarian and medical help, and much more. Thousands of videos of the conflict are disseminated daily. ‘Social media’ have thereby helped to co-ordinate Ukrainian defence, evacuation and humanitarian activities at home, while the whole world watches the conflict live.

In an attempt to curb this process, Moscow has sought to export its well-established disinformation practices into Ukraine. In early March, television towers were attacked in Kyiv and Kharkiv. The broadcasting tower was seized by the Russian invaders in Kherson, with local television and radio channels switched to Russia-promoting video and audio messages. The Russian-appointed ‘acting mayor’ of Melitopol has urged that local people switch to Russian television channels for ‘more reliable’ information. These strategies are designed to enforce a false narrative around Russia’s invasion, as well as revising the whole history of Ukraine-Russia relations.

Lessons from the information wars

All in all, several polls from diverse polling organisations have reported that the silent majority of Russians—roughly 60 per cent—initially favoured the use of force in Ukraine and polls have also registered rising support for Putin. Many factors may potentially help explain these results.

Putin’s domestic control rests on hard power—harsh coercion of opponents, such as the imprisonment of Alexei Navalny. But it also depends on soft power, notably cultural values and feelings of nationalism reinforced by state control of television news and newspapers, following the gradual crackdown on the free press during recent decades, accelerated by recent draconian restrictions on independent channels.

Official censorship has aggressively throttled independent sources of news about Ukraine. Self-censorship is likely to have reinforced a spiral of silence in society, with perceptions of majority support amplifying official propaganda while silencing critics.

The Ukrainian conflict, as with other modern conflicts, involves a complex combination of hard-power military force and soft-power information wars. So far on the world stage, following the unprovoked attack on a sovereign state, the moral clarity of refugees and the bravery of the resistance, Ukraine has achieved an overwhelming soft-power ‘victory’. This is indicated by the almost universal condemnation of the invasion and call for unconditional Russian withdrawal coming from the United Nations General Assembly.

But unless that message also penetrates hearts and minds at home throughout Russia, sparking active dissent and domestic outrage against a war which is wrecking both countries, Putin’s rule will remain unchallenged. In the interim, while the free world watches in horror, hard power continues to turn Ukrainian cities into rubble.

This first appeared on the London School of Economics EUROPP blog