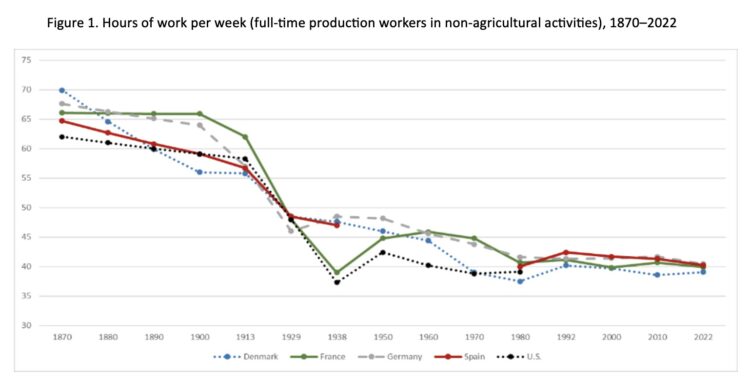

From the late 19th century until the 1980s, there were consistent and significant reductions in the number of hours that full-time workers devoted to work in Europe. However, a clear historical shift occurred in the 1980s: since then, full-time workers have continued working roughly the same number of hours per week up to 2022, as seen in Figure 1. Why do regular workers continue working the same number of hours despite technological advancements and productivity gains? This is one of the questions addressed in a recent study by the Joint Research Centre of the European Commission. Only if we include part-time workers in the analysis (see Figure 3 in the cited study) can we observe a continuation in the historical trend of working time declines for the average worker. Although, even in this case, there is a clear slowdown from the 1980s compared with previous periods. This implies that part-time work has played a key role as the main driver of aggregate reductions in working time in recent decades in Europe.

Why do full-time workers continue working the same hours?

In the six EU countries we focus on, full-time workers represent 3 out of 4 employees, and they work roughly the same number of hours as they did in the 1980s. This is due to countervailing forces influencing their work schedules, which together explain the relative stability of working hours among full-time employees over time.

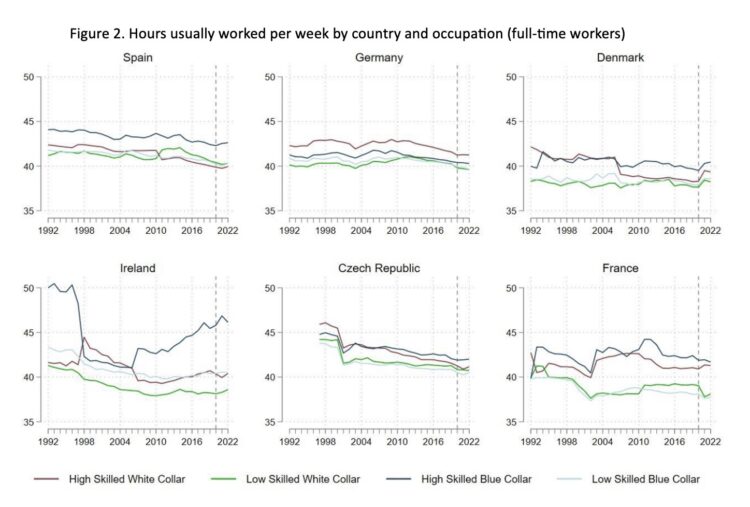

On the one hand, structural economic changes partially explain why full-timers continue registering long working hours. Longer hours are typically worked by high-skilled workers and in private services. Therefore, occupational upgrading and the notable growth of private service jobs have pushed working time up in the last decades. On top of this, there is a cultural shift having a similar effect. While in the past, leisure was used to signal status, nowadays, the opposite happens, with time at work and “busyness” being used as status markers. This is consistent with the following observation: high-skilled workers, that is, those who usually have higher autonomy and control at work, tend to work more hours than low-skilled workers (see Figure 2). From an individual (and economic) perspective, this could also be interpreted as a substitution effect: the opportunity cost of leisure is higher for those earning more, making them decide to work longer hours.

On the other hand, other sectoral trends are pushing full-time working hours in the opposite direction. These are mainly the expansion of public services (where shorter working hours are typical), the declining weight of the goods-producing sector (which historically involved long working hours), and the reduction in both the prevalence and time intensity of self-employment.

While on aggregate working time has slightly decreased in Europe in the last decades, this is because of the expansion of non-standard forms of work, mainly part-time. In the meantime, most workers (those that work on a full-time basis) have continued doing similar hours. For this reason, reductions in working time are still considered by many as a mirage.

The expansion of part-time work: the main driver behind reductions in working time

As noted above, since the 1980s, reductions in working time in Europe are only evident when part-time workers are included in the analysis. The rise and establishment of part-time work has been the primary driver of aggregate work time reductions in recent decades.

Indeed, part-time workers work approximately half the number of hours of their full-time counterparts. As part-time contracts gain importance (in the six countries in our sample, part-time employment rose from 16 per cent of total employment in 1992 to 24 per cent in 2022), they will automatically reduce average working hours. Compared to the 1980s, there are more people employed, especially women; however, employment has also become, on average, more fragmented (and less time-intensive for those outside the full-time norm).

What are the main factors explaining the expansion of part-time work? Since the 1980s, regulatory changes and the shift towards de-standardisation of the employment relationship enabled the development of more flexible and less time-intensive employment options, such as part-time work. These new forms of work became more prevalent among women and in the service sector (see Figures 5 and 6 in the reference study). That is why we consider that the tertiarisation of the economy and the feminisation of employment are two major factors contributing to reductions in working time, as they supported the expansion of part-time work.

Conclusions and policy implications

After a long period of consistent reductions in working hours (1870-1980), trends in Europe stabilised around a segmented pattern, with the bulk of workers still following the norm of 40 hours a week. A growing share of non-standard workers have shorter and more flexible schedules. If average working hours have reduced slightly since then, it is largely due to the growing prevalence of part-time work. However, the majority of workers (those with full-time schedules) still work as long as they did in the 1980s. Structural transformations, such as the expansion of private services and occupational upgrading, along with changing attitudes towards work (fostered by status competition and changing work values), have contributed to this stabilisation and prevented further reductions in full-time working hours.

Reductions in working time, exemplified by the four-day workweek proposal, are a prominent topic in current European debates. This attention is warranted, given that most European workers have not experienced significant reductions in working time for decades. The narrative that technological progress has led to decreased workloads rings hollow for many, as they continue to work long hours despite advances in computerisation, automation, and artificial intelligence.

Meanwhile, around 20 per cent of part-time workers in the EU are trapped in involuntary part-time employment, working fewer hours than they desire. Future working time policies in the EU should address these imbalances directly, acknowledging the underlying segmentation of employment conditions. Promoting a more equitable distribution of work and leisure, policies can benefit full-time workers by reducing their working hours. Conversely, policies that incentivise companies to offer extended hours to part-time workers who desire them could improve the quality of non-standard jobs, aligning with the broader goal of enhancing job quality.