Do you behave more like an ape or a human? If you have to share some money (or some raisins!), do you give away as little as possible and keep as much as you can for yourself, or do you share equally? Mainstream economic theory has traditionally worked on the basis that human behaviour can largely be explained in terms of inherent self-interest – a tendency to maximise gain for ourselves. Economists coined the term homo economicus, or “economic man”, for this conceptualisation of humans as rational and self-interested back in the nineteenth century, drawing on the assertions of John Stuart Mill and Adam Smith that we will want to do the least amount of work for the most amount of gain and that we cannot rely on the benevolence of others but must look out for ourselves.

Obviously, this is a simplistic presentation of our utilitarian tendencies, but it underpins assertions like those promulgated in Steven D. Levitt and Stephen J. Dubner’s 2005 book, Freakonomics – that our behaviour is shaped by our conscious and subconscious self-interest, what their book describes as “the hidden side of everything”.

Humans, however, are nowhere near that simple. But chimpanzees are – in behavioural experiments they perform exactly as economic theory suggests that humans will behave, acting as self-interested so-called “rational maximisers” in what is known as the Ultimatum Game. In this experiment, participants are paired and a known sum of money is given to one, the “proposer”, who must then divide it as they please with the “responder”. The responder accepts or rejects the offer. If rejected, neither gets anything; if accepted, they both keep the share of money offered.

Economic theory suggests that responders should accept any offer, however small, because there isn’t going to be a next time and something is better than nothing. And proposers should offer the smallest possible amount, just enough to get the responder to accept it, however derisory. When chimpanzees play the game (with raisins rather than cash), they behave exactly as the theory predicts: they will take what they are offered and are not sensitive to fairness.

Humans, on the other hand, reassuringly, are very sensitive to norms of cooperation and fairness. Human “proposers” most often offer half the money rather than the smallest amount they think they can get away with, and human responders tend to reject anything below 20 per cent, even though that means they get nothing. Homo economicus we most definitely are not. And in a fascinating slant, it appears that even apes will act in the interests of others (prosocially) in the Ultimatum Game, rejecting unfair offers, if the responder has access to alternative offers.

Interestingly, the Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences for 2025 has been split, and not in equal shares, between three recipients: one half of the prize goes to Joel Mokyr, while the other half is divided between Philippe Aghion and Peter Howitt. The award is for “having explained innovation-driven economic growth“, according to the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences.

Economics is the only social science that has a Nobel Prize. And there are some who sneer that it is not really a proper one. Alfred Nobel’s 1895 legacy created the Nobel Prizes for Physics, Chemistry, Physiology or Medicine, Literature and Peace, reflecting his own areas of achievement and interest. The prize for economics is more correctly known as the Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel. It was founded much later, in 1969, and is funded by the Swedish central bank.

Some might sneer even more if they reflected on whether some of the recipients of the so-called Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences would meet the criterion stated in Alfred Nobel’s will of being “those who, during the preceding year, shall have conferred the greatest benefit to humankind”. Among past winners are Friedrich von Hayek and Milton Friedman, key architects of neoliberalism.

The outsized influence of economics

But the fact that only economics gets a Nobel Prize is emblematic of its dominance in the social sciences. Economics punches far above its weight in the world of policy and politics. Despite being tagged “the dismal science” since the term was introduced in an 1849 tract by Thomas Carlyle arguing for the reintroduction of slavery, modern economics has captured the attention of politicians and policymakers to a degree that the other social sciences can only envy from their distant position outside the corridors of power. And the Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences adds such lustre to the discipline that it sometimes allows economic thinking and economists to enter policymaking arenas that are beyond its remit and their expertise.

While I was an assistant professor at the University of Chicago, one of its many economics Nobel laureates was the star speaker at a conference organised by some of my colleagues in the medical school to discuss the social determinants of health. Opening the conference, the economist’s talk on health inequalities ended with a call to address racial and social-class inequalities in babies being born with low birth weight. What could be done to tackle high rates of low birth weight in these populations, asked a member of the audience? Improve social support, suggested the eminent economist, implement social-support interventions.

He didn’t seem to be aware that interventions of exactly that nature had been trialled and failed. If we were going to discuss interventions for low birth weight, why weren’t we listening to the doctors and child-health experts, many of whom were in the audience, if not on the stage?

What I observed all those years ago in Chicago – an economist talking with authority about an area in which he had no expertise – is common enough to have a name: economics imperialism. In a masterly historical account, Matthew Watson, professor of political economy at the University of Warwick, traces the development of the mathematical market models that have come to dominate economics, and which allow economists to dazzle us with what looks like hard science and inarguable logic (and most importantly, numbers). Watson points out the important distinctions and differences between what he calls the “world within the model”, in other words the world as depicted by a mathematical model, and the “real world”, or the world as it is experienced in everyday life.

In the real world, rather than rewarding work on growth, many outside of economics – and increasingly many within the discipline – argue that the focus on economic growth is a big problem. It’s as wrong-headed and outdated as the idea of homo economicus. Perhaps, instead of economists invading non-economic arenas, we actually need more non-economists and more non-traditional economists taking a cold, hard look at this traditional economic objective.

Beyond GDP: measuring what matters

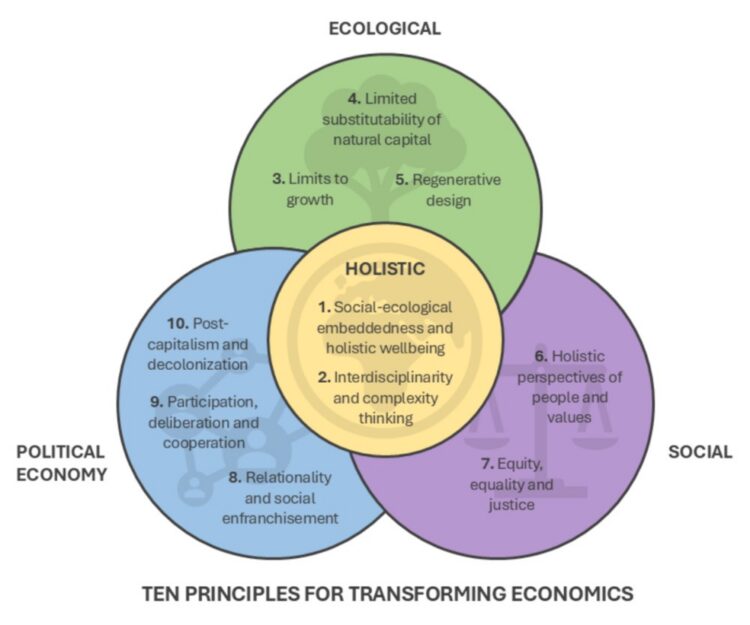

One sign of progress is the High-Level Expert Group commissioned by the United Nations to develop a new framework that does a better job than Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in measuring societal progress. They are tasked with coming up with indicators of sustainable development to create a country-level dashboard that will help societies think about what they really want to grow, for example focusing on well-being instead of GDP. This is an application of new economic thinking, which has recently been synthesised by the Global Assessment for a New Economics (of which I’m a member) into ten ecological, social, political economy and holistic principles, cutting across 38 different new economic approaches. It’s this kind of thinking that the world needs to transform economic systems to tackle the interacting global crises we face.

Ten Principles for Transforming Economics in a Time of Global Crises, Kenter et al, Nature Sustainability (2025)

So far, the Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences has been seemingly blind to ecological economics and most of the flavours of new economic thinking identified by the Global Assessment for a New Economics. The 1998 prize to Amartya Sen for welfare economics and concepts of capabilities, the 2002 prize to Daniel Kahneman for bringing psychology into economics, and the 2009 prize to Elinor Ostrom for work on the commons are as close as the Swedish Academy has got to new economic thinking.

It feels as if we are still some distance away from dethroning growth in GDP and putting well-being, equality and justice at the heart of our economic systems. While we wait, can I offer you half of my raisins?

This is a joint column with IPS Journal

Kate Pickett is professor of epidemiology, deputy director of the Centre for Future Health and associate director of the Leverhulme Centre for Anthropocene Biodiversity, all at the University of York. She is co-author, with Richard Wilkinson, of The Spirit Level (2009) and The Inner Level (2018).