In a recent speech, President Christine Lagarde of the European Central Bank (ECB) articulated a clear desire for the euro to play a more significant role as an international currency. This, she argued, could bring substantial benefits to the euro area: “It would allow EU governments and businesses to borrow at a lower cost, helping boost our internal demand at a time when external demand is becoming less certain. It would insulate us from exchange rate fluctuations, as more trade would be denominated in euro, protecting Europe from more volatile capital flows. It would protect Europe from sanctions or other coercive measures.”

Ms. Lagarde’s aspiration is that a greater reserve role for the euro would bestow upon Europe some of the so-called “exorbitant privilege” that has, until now, been exclusively enjoyed by the United States. This ambition stands in stark contrast to the views expressed by the Deutsche Bundesbank several decades ago, which in 1972, explicitly referred to “The Deutsche Mark as a reluctant reserve currency.”

The Exorbitant Privilege: A Double-Edged Sword

The term “exorbitant privilege” was coined in the 1960s by Valéry Giscard d’Estaing, then the French Minister of Finance. It describes the unique position of the United States, which allows it to sustain a permanent current account deficit without triggering an exchange rate crisis.

The underlying mechanics are straightforward: when a country imports more than it exports, its liabilities to the rest of the world increase. Exporters abroad accumulate higher deposits denominated in the importing country’s currency. If these exporters are unwilling to increase their exposure to a deficit country, they typically sell their export receipts on the foreign exchange market, exchanging them for deposits in their own currency. Consequently, the currency of the deficit country depreciates. If the country fails to address its deficit, the exchange rate will continue to depreciate, risking a currency crisis.

This dynamic changes significantly with the “exorbitant privilege.” Foreign investors are willing to increase their holdings of US Treasuries by exchanging US dollar deposits, thereby financing the current account deficit without the dollar depreciating. Therefore, it is a complete misconception for President Donald Trump to interpret the US current account deficit as exploitation of the United States by the rest of the world. As he once stated, “The United States of America is going to take back a lot of what was stolen from it by other countries.”

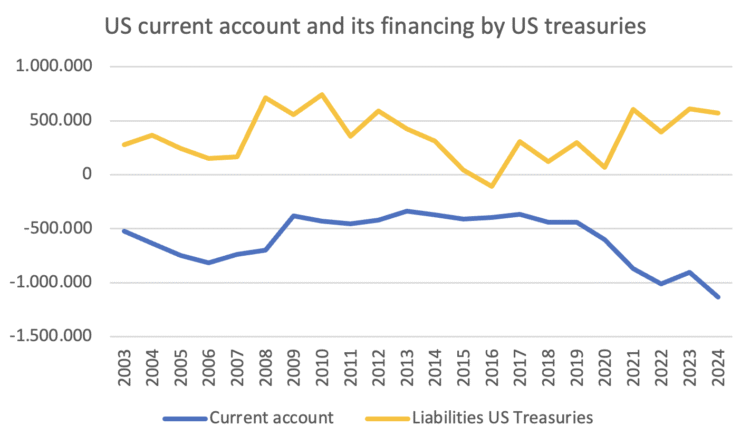

The opposite is true: The current account deficit has enabled US citizens to enjoy a higher standard of living, financed by the rest of the world through the purchase of US government IOUs. Over the past two decades, the current account deficit and the amount of Treasuries purchased by foreigners have moved in roughly tandem.

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis

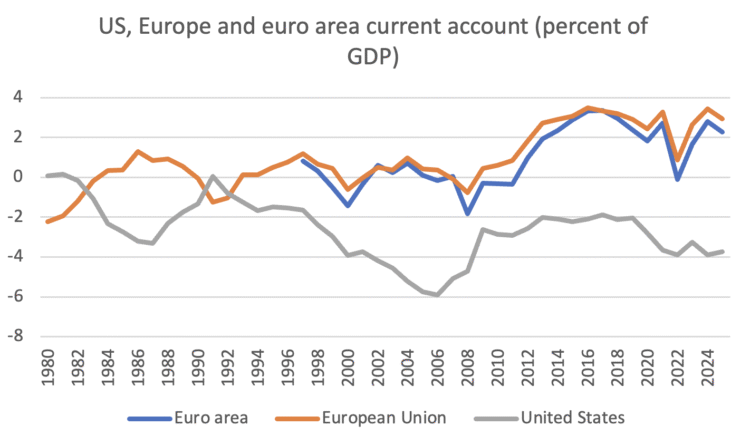

If President Lagarde is now arguing that Europe could benefit from such a privilege by increasing the reserve role of the euro, one must recognise that Europe and the euro area have, until now, typically been current account surplus countries. As long as this fundamental situation remains unchanged, Europe does not require the “privilege” of foreigners purchasing euro-denominated government securities.

Source: IMF, World Economic Outlook Database

Given this entirely different current account position, it is unclear whether Europe would genuinely benefit from making euro government bonds more attractive as foreign exchange reserves. If foreigners were to increase their holdings of euro area government bonds, they would need to purchase euro deposits on the foreign exchange market against other currencies. This would lead to an increase in the effective exchange rate of the euro, resulting in a deterioration in the price competitiveness of euro area producers. It was precisely this fear that prompted the Bundesbank to adopt a cautious approach to an increased reserve currency role for the D-Mark in the 1970s.

Therefore, when discussing the “exorbitant privilege,” it is crucial to recognise its dual nature. For a currency area with a structural deficit, it prevents the currency from depreciating. For a currency area with a structural surplus, however, it causes an appreciation of the currency, which can have negative effects on its price competitiveness.

Switzerland provides a compelling example. Traditionally, it has maintained a structural current account surplus. The Swiss franc enjoys a strong reputation as a global reserve currency, leading to permanent capital inflows. To prevent destabilising appreciation of its currency, the Swiss National Bank has had to purchase massive amounts of foreign currencies. With reserves exceeding 900 billion US dollars, it is now the third-largest holder of foreign exchange reserves in the world, surpassed only by China and Japan. A significant portion of these reserves is invested in government bonds.

It would be ironic if the ECB, by increasing the reserve role of the euro, had to intervene to prevent a depreciation of the dollar and invest these funds in Treasuries.

How Can Investors Be Convinced?

However, if the aim is to increase the international role of the euro, it is necessary to determine how to boost this process. Since its introduction in 1999, the euro’s share of global exchange reserves has stabilised at approximately 20 percent after some fluctuations. The euro has not, however, benefited from the decline in the US dollar’s share, which has fallen from over 70 percent to under 60 percent. Instead, other currencies such as the Swiss franc, the pound sterling, and the Japanese yen have been able to increase their position as reserve currencies. Therefore, it is unclear whether the euro would benefit from future shifts in international investors’ portfolios away from the US dollar due to “Trumpian policies.”

In her speech, President Lagarde described the “economic foundation” of a reserve currency role as a virtuous circle between “growth, capital markets and international currency usage.” She explained, “The development of US capital markets boosted growth… while simultaneously establishing dollar dominance. The depth and liquidity of the US Treasury market in turn provided an efficient hedge for investors.”

Ms. Lagarde believes that “Europe has all elements it needs to produce a similar cycle” and concluded: “If we truly want to see the global status of the euro grow, we must first reform our domestic economy.” The “reforms” she outlined included the usual suspects: completing the Single Market, enabling start-ups, reducing regulation, and building the savings and investment union.

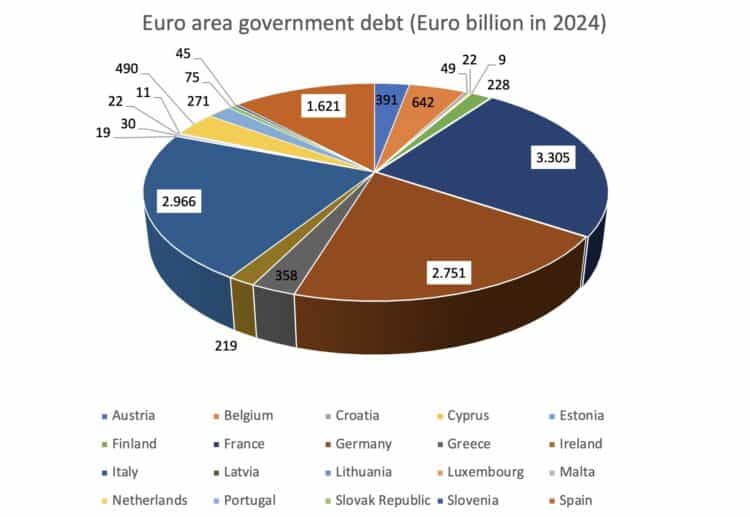

Surprisingly, she did not mention the most obvious obstacle to the euro playing a more prominent international role. While US capital markets offer a total treasury supply of 28.3 billion US dollars, the euro area’s government bond market remains a patchwork of larger and smaller national issuers. The largest volume is provided by the French market, totalling 3.3 billion euros.

Source: IMF, World Economic Outlook April 2025

It would be naïve to believe that this fundamental deficiency of European capital markets could be overcome by “structural reforms” or by the more homeopathic measures for completing the capital market union.

However, President Lagarde also offered a promising step forward: a joint financing of European public goods, particularly defence. This would help to increase the supply of truly European safe assets.

In sum, there is no obvious case for increasing the role of the euro as a global reserve currency. If the ECB wants to allow “businesses to borrow at a lower cost, helping boost our internal demand,” it must simply reduce its policy rate further. In addition, the fundamental flaw of a segregated market for European government bonds is very difficult to overcome. Nevertheless, attempts to finance European public goods with jointly issued bonds will undoubtedly lead in the right direction.

This is a joint column with IPS Journal