Financial integration is not the problem, writes Peter Bofinger. It is the still national segmentation of government bonds.

The completion of the capital-markets union is high on the agenda of European Union politicians. The French president, Emmanuel Macron, and the German chancellor, Olaf Scholz, wrote in the Financial Times in May:

We need to unlock the full potential of our capital markets. Too many companies looking to fund their growth turn to the other side of the Atlantic. Too many European savings are being invested abroad rather than in Europe’s most promising start-ups and scale-ups.

In recent months, the European Council, the European Central Bank Governing Council and, in his report on the EU single market, the former Italian prime minister Enrico Letta have all attributed key importance to the capital-markets union for European competitiveness.

Indicators of integration

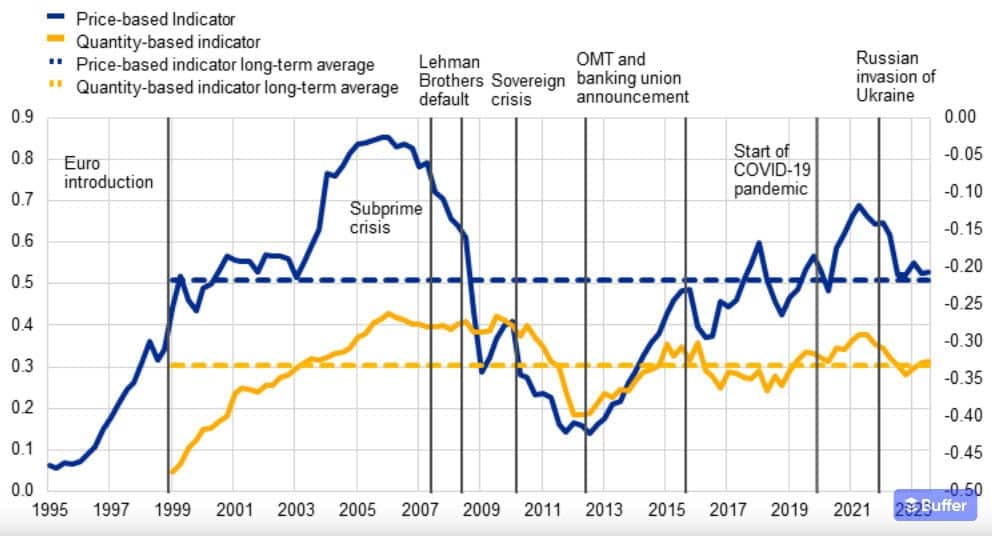

While calls for a deepening of this union are plausible in principle, the question arises as to how great the obstacles to financial flows remain: all restrictions on capital movements within the EU were abolished on July 1st 1990, when the first stage of monetary union was entered. The indicators of financial integration, price- and quantity-based, regularly compiled by the ECB provide a good basis for an answer (Figure 1). They are bounded between zero (full fragmentation) and one (full integration).

The price-based indicator relies on measures of the dispersion across member states of returns to assets, such as the standard deviation of certain interest rates. It aggregates ten indicators for money, bond, equity and retail-banking markets. The quantity-based indicator utilises data on cross-border holdings for different classes of asset (such as bonds or equities) across different sectors. It aggregates five indicators for the same market segments, except retail banking.

Figure 1: price- and quantity-based composite indicators of financial integration

From the mid-1990s to 2006, the price-based indicator came very close to the value of one—perfect integration. The financial crisis halted this development, which had not been without its problems, and led to a stronger segmentation of financial markets within the monetary union. In principle though, the existing regulations allow of a high degree of financial integration within Europe.

The Letta report says: ‘A concerning trend is the annual diversion of around €300 billion of European families’ savings from EU markets abroad, primarily to the American economy, due to the fragmentation of our financial markets.’ But this figure amounts to nothing other than Europe’s surplus on its current account. Given the key factors explaining current-account balances—differences in economic growth, exchange rates, labour costs—it is somewhat naïve to attribute this to barriers to intra-European financial flows.

Qualitative leap?

Given the high degree of financial-market integration already achieved, to what extent can a qualitative leap be expected from the measures under discussion? These focus on three main areas.

The market for the securitisation of bank loans is to be revived. Securitisation however played an inglorious role in the crisis of 2007-08. Enabling banks to remove loans from their balance sheets and sell them to investors in bundled and securitised form incentivises them to be less careful when selecting their borrowers: they can sell on the loans to third parties. If there are now discussions about relaxing the regulatory requirements for these instruments, care must be taken to ensure the associated ‘moral hazard’ is not recreated.

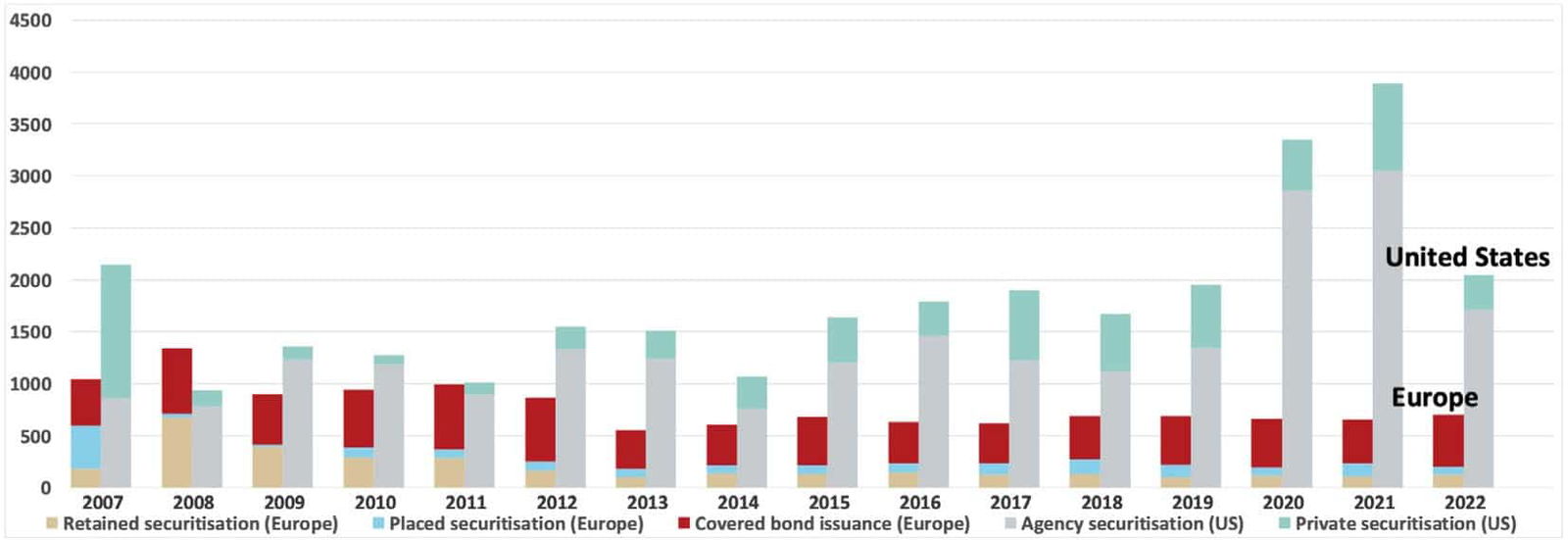

It is frequently rehearsed that the market for securitised entities is many times larger in the United States than in Europe. But in the US these are private property loans guaranteed by quasi-governmental institutions (Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac). In other securitisations, Europe is even ahead of the US due to its focus on covered bonds, where the loans are collateralised against a pool of assets in case the issuer fails (Figure 2).

Figure 2: issuance volumes of securitisations and covered bonds in the US and Europe (EU27 plus UK) (€ billion)

Financial integration in Europe is also to be driven forward by a harmonisation of insolvency law. This may be helpful for the securitisation market but it is unlikely to be a priority for investors seeking shares or start-ups to support. It protects creditors but not shareholders or other investors with an equity stake.

In addition, a simple and effective cross-border investment and savings product for all is to be developed. The ECB hopes this will ‘unfreeze’ a share of unproductive deposits held by euro-area households. These could allocate their savings more efficiently within the banking union and participate more actively as retail investors in capital markets.

Households have however been able to invest their savings freely in all member states since 1991. With instruments such as exchange traded funds (ETFs)—baskets of securities which can be traded on the EuroStoxx 50 or the Stoxx Europe 50—they can invest in a diversified manner in corporations throughout the EU.

Not a game-changer

There is nothing to be said against reducing barriers to financial integration in Europe. But this is not a game-changer that will trigger real economic impetus.

Surprisingly, the discussion about the capital-markets union usually leaves out an area where a qualitative leap would be possible. As the Letta report notes, the eurozone capital market suffers from segmentation of the market for government bonds along national lines. It therefore lacks the depth and so liquidity of the market for US government bonds, which makes them particularly attractive for international investors, especially central banks.

This leads to a proposal aired many years ago by Jacques Delpla and Jakob von Weizsäcker:

Euro-area countries should divide their sovereign debt into two parts. The first part, up to 60 percent of GDP, should be pooled as ‘Blue’ bonds with senior status, to be jointly and severally guaranteed by participating countries. All debt beyond that should be issued as purely national ‘Red’ bonds with junior status.

Even if the proposal is not without its problems—in particular the idea that there should be an insolvency risk for the ‘red’ bonds—it could in principle create a large integrated European capital market for secure assets. The ECB describes the advantages thus:

Safe assets play a vital role in financial resilience and stability. The wider availability of safe assets, including at EU level, would facilitate monetary policy transmission, support EU public goods financing, and foster financial stability and integration.

As NextGenerationEU shows, a larger market for secure assets could of course also be established by a joint financing of investment projects in Europe, fostering its ecological and technological transformation.

Overall, the discussion about a European capital-markets union gives the impression that small-scale institutional changes could achieve a qualitative leap, when a very high level of financial integration has already been achieved. Conversely, it generally ignores Europe’s decisive disadvantage compared with the US in the fragmentation of the markets for government bonds.

This is a joint publication by Social Europe and IPS-Journal

Peter Bofinger is professor of economics at Würzburg University and a former member of the German Council of Economic Experts.