For the second time, the Economist has diagnosed Germany as ‘the sick man of Europe’.

The first was in 1999, when the country was suffering from high unemployment. But it is debatable whether this betrayed chronic illness—rather than being the inevitable consequence of the massive unification shock to the utterly unproductive economy of East Germany.

That West Germany, with a population of 61 million, was able to extend its generous social-security system to 16 million east Germans, while at the same time completely rebuilding the crumbling infrastructure in the east, was an indication of the strength of its economy at the time. In 2004, I wrote a book, Wir sind besser, als wir glauben (We are better than we believe), challenging the negative diagnosis of German competitiveness.

Weak growth

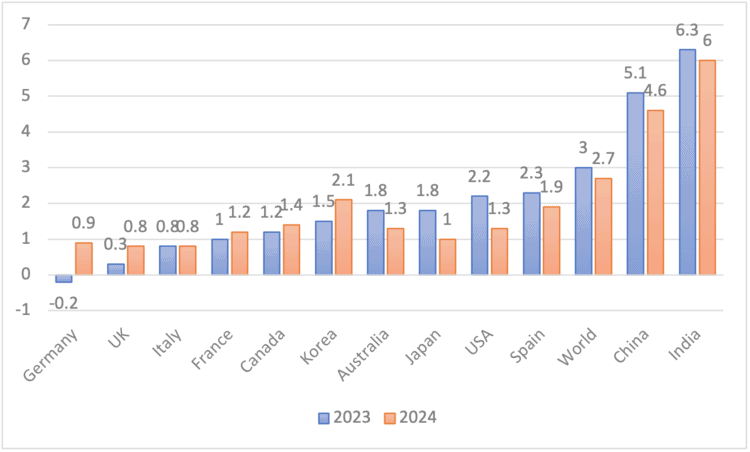

But today that diagnosis seems more apt. One obvious indication is the weak growth of the German economy. According to the latest forecast from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (Figure 1), Germany is the only country apart from Argentina whose gross domestic product will decline in 2023. In 2024, it will still be one of the countries with very weak growth.

Figure 1: OECD GDP growth forecasts (%)

Of course, Germans are aware of this poor performance. But in the public debate the main culprit is ‘bureaucracy’—the government. While German bureaucracy is often slow and inefficient, one has to ask whether this really explains the underperformance of the economy.

The International Institute for Management Development provides an annual international ranking of government efficiency. In 27th place, Germany’s bureaucracy is not outstanding. But its competitors tend not to fare much better: the United States ranks 25th, the United Kingdom 28th and China 35th, while Japan, France, Spain and Italy are even further adrift.

So if German bureaucracy is a drag on growth, there must still be deeper problems. These can be easily identified by exploring the specific features of the German economy’s ‘business model’. Compared with its competitors, this model can be described by three concentric circles.

Export orientation

The outer circle is a pronounced export orientation. Since the 1990s, in Germany the ratio of exports to GDP has almost doubled. At 47 per cent, it is much higher than for France and the UK (29 per cent), China (20 per cent) and, particularly, the US (11 per cent). In the period of rapid globalisation, exports boosted the German economy, while high surpluses on the current account reflected the lack of domestic demand.

But today, with rising protectionism—not only in China but especially the US—world trade is no longer an engine of growth. Germany can rely no more on other countries stimulating its economy.

The middle circle of the German economic model is a strong focus on manufacturing: its share in value added (19 per cent) is again much higher than in the US (11 per cent) and indeed more than double that in France and the UK (9 per cent). While Germany has benefited from its strong industrial base for decades, high energy prices and the need to decarbonise the economy are much harder to absorb than in countries with a strong services sector.

In that arena, Germany (like its European peers) suffers from a lack of digital platforms. A recent study by the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung shows that the US accounts for 80 per cent of the global market value of such platforms; China has 17 per cent and Europe as a whole only 2 per cent.

Within manufacturing, the inner circle is the German automotive sector, which has a very high concentration of sales in the Chinese market. Car production in Germany peaked in 2017. Today, production is still below the levels preceding the 2008 financial crash.

Volkswagen’s real difficulties in the Chinese market reflect the underlying problems of German carmakers. For too long, they not only relied on combustion engines but also underestimated the importance of digital services. Volkswagen’s dependence on a relatively small Chinese company (XPENG) to improve the digital performance of its cars shows how times have changed: Germany used to supply advanced technologies to China; today, Chinese battery companies (CATL) are exporting advanced technologies by investing in Germany.

Ordnungspolitik

So the diagnosis popular in the German media (and among many German economists) that bureaucracy—and associated high taxes—is the country’s main problem misses the point. The German economy is facing a fundamental challenge to its business model which cannot be addressed by removing regulations and cutting taxes. What is needed is a comprehensive transformation, which above all requires a new economic paradigm.

The German economic debate remains however dominated by the unshakeable belief of leading economists in the virtues of the market. Ordnungspolitik, a word that cannot be translated, is the battle-cry of German economic orthodoxy. In a recent interview, Veronika Grimm, a member of the German Council of Economic Advisers, nicely presented this article of faith (my translation):

The state does not know better than the economic actors where the future opportunities lie. Moreover, one must not forget that politics is massively influenced by interest groups. And they often fight to preserve the status quo or at least to slow down the pace of change.

The most obvious implication of Ordnungspolitik is the Schuldenbremse (debt brake) enshrined in the German constitution in 2009. This in effect requires balanced budgets, so that neither the federal government nor those of the Länder can finance productive public investments with debt.

This rule, which does not exist in any other major country, implicitly makes public debt the most important concern, to which all others in the real economy are subordinated. Given Germany’s debt-to-GDP ratio is by far the lowest among the G7 countries, with the debt brake it attaches highest priority to its least urgent problem.

Limited fiscal space

It will thus be very difficult for Germany to restructure its economy successfully. The prohibition on financing public investment with debt limits the fiscal room for manoeuvre to boost domestic demand.

The major decline in construction caused by high interest rates would provide an ideal opportunity for investment in social housing. Migration has made it very difficult, if not impossible, to find housing at reasonable prices in Germany’s major cities. Yet at a special housing summit organised by the government last month, the housing minister was unwilling or unable to increase the budgetary allocations beyond a very low €1.3 billion this year and €1.6 billion next.

The necessary reorientation of German manufacturing towards new technologies and services is also a victim of the debt brake. While such a transformation needs to be supported by large-scale efforts in research, public spending in this area is in free fall.

This is all the more worrying given that as things stand Germany does not play a dominant role in high-tech research. In a recent ranking of research efforts in 64 innovative technologies (Figure 2), China was by far the most active, followed by the US. Germany finished behind India, South Korea and the UK.

Figure 2: ‘medal table’ for research in new technologies

| Gold | Silver | Bronze | 4th rank | 5th rank | |

| China | 53 | 11 | 1 | ||

| US | 11 | 47 | 5 | 1 | |

| India | 5 | 17 | 9 | 5 | |

| South Korea | 1 | 5 | 10 | 10 | |

| UK | 18 | 14 | 12 | ||

| Germany | 8 | 16 | 3 | ||

| Italy | 5 | 4 | 2 | ||

| Japan | 2 | 1 | 4 |

But it is not just lack of public funding that is holding back the transformation of the German economy. While in China and the US, but also in many smaller countries, the state plays a decisive role in shaping the ecosystem for new technologies, many German economists are strongly opposed in principle to a ‘subsidy race’. In April the Gemeinschaftsdiagnose of leading German economic-research institutes advocated (my translation): ‘Location policy instead of industrial policy. Leave subsidy races to others.’ As a result of this passive approach, German carmakers such as Mercedes and Volkswagen have moved production of electrical vehicles to north America, where they can take advantage of the generous subsidies provided by the US Inflation Reduction Act or Canada’s matching arrangements.

Regaining health

So this time the diagnosis is correct: Germany has become sick. But it could be cured if it were willing to change its lifestyle and take the medicine needed to regain its health.

The lifestyle change requires a new way of thinking: instead of an often unconditional trust in market forces, a more nuanced view is needed, which sees government not only as a problem (‘bureaucracy’) but also as a solution to problems markets cannot ‘solve’ by themselves. The medicine is public debt deployed as an engine of growth—not by reducing taxes and accompanying transfers but by increasing public investment to stimulate domestic demand and the emergence and deployment of new technologies.

This is a joint publication by Social Europe and IPS-Journal

Peter Bofinger is professor of economics at Würzburg University and a former member of the German Council of Economic Experts.