The potential risk of service-sector offshoring, against a backdrop of economic globalisation, is nothing new. As early as 2007, the American economist Alan Blinder highlighted the risks offshoring posed to 46 occupations in the United States.

More recently, but before the pandemic, Richard Baldwin argued that ‘teleworking’, along with the emergence of artificial intelligence, would bring a major realignment with significant implications—a new wave of globalisation, this time of the service sector. Baldwin used the term ‘telemigration’ to refer to individuals who would, as a result, be living in one country while working for a company based in another.

Yet to materialise

On the whole, though, these feared changes have yet to materialise—at least to the extent predicted. In his study of the occupations mentioned by Blinder, Adam Ozimek, chief economist at Upwork, finds no widespread offshoring of US jobs. So far, firms have largely responded to the opportunities afforded by the internet and communications technology by hiring more remote workers in the US and using more freelances.

In an analysis of the number of telemigrants this year, Baldwin and Jonathan Dingel have yet to find a significant impact in terms of jobs. They do not however rule out the possibility that a ‘modest change in trade could have large effects’.

While quantitative studies provide some insight, the larger picture proves more difficult to decipher. First, a credible threat of offshoring—even if it only affected a limited number of workers in reality—could itself lead to a deterioration in working conditions and wages.

Secondly, an analysis of the timeframe and the impacts, in terms of outsourcing and changes in working conditions, allows three potential stages towards offshoring to be discerned. These may overlap and develop at different speeds.

Widespread telework

The first stage is similar to the phenomenon, rendered familiar by the pandemic, of widespread telework. It allows for standardised remote monitoring and performance evaluation, affecting a very large number of categories of workers, across a range of sectors and occupations not previously considered structurally suitable.

This often puts the financial cost directly on to workers, to purchase suitable equipment as required, with possible health-and-safety implications. Indirectly, too, it imposes a cost in terms of workspace: studies indicate that half of those working from home use their bedroom or kitchen. Companies can meanwhile reduce the costs of renting offices or branches—this is particularly prevalent in banking, for example.

Blinder’s table shows, as revised, that the range of possibilities is increasing in this initial phase.

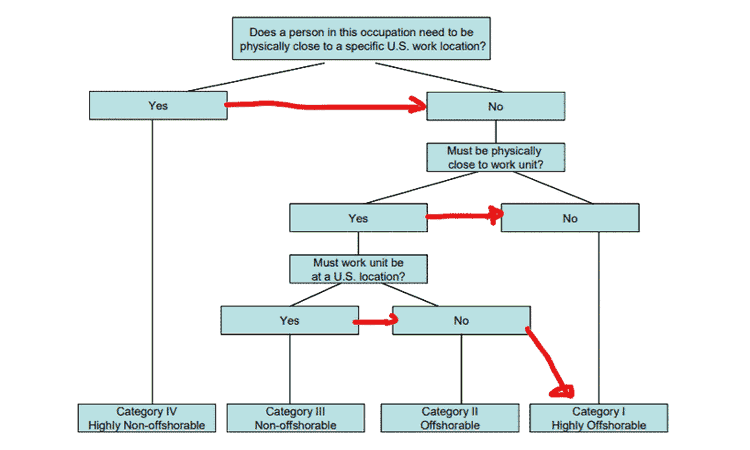

The four broad occupational categories

At this stage, employers may choose independent contractors—whether that be a service contract or engaging a subcontractor or freelances—over employees. For the GAFAM (Google, Apple, Facebook, Amazon, Microsoft) Big Tech companies, this is already the case: Google now has more independent subcontractors than employees.

The development of project-based work could facilitate this evolution. In their nature, teams change according to projects and can easily integrate company employees and collaborators of different status(es).

Lower costs

In the second phase, work is no longer performed from the usual location of the company’s headquarters but from one chosen by the worker. For European Union citizens, this could be anywhere in their country or within European territory. In this scenario, employees are no longer in situ, available to be mobilised in exceptional circumstances, meaning that work must be better planned. Le Monde reported on a company which paid its employees’ travel and accommodation for a monthly meeting lasting a few days—it no longer mattered whether a worker was in Nantes, Porto or Sofia.

While employees bear the costs of adaptation, they can potentially reduce these by inhabiting an environment where housing and general living costs are lower. As the Upwork study shows, freelances in the US are on average based in areas where costs are lower than those faced by their contracting parties.

Under such conditions, however, why wouldn’t employers decide to work with someone—whether employee or freelance—from a country with lower wages and social security, or pay different wages for the same task based on the worker’s location?

Offshoring from the EU

The third phase entails offshoring from the EU. This is already common in several professions: accounting, information technology, call-centre operation, secretarial work, after-sales service, translation and so on.

If the system works within the EU, why wouldn’t employers be tempted to seek out countries with well-trained but much cheaper labour? Africa, which shares European time zones—and whose citizens are increasingly well-trained and speak several languages—could be an attractive location, particularly for customer service where the time variable remains important.

There are obviously limits to this, including securing visas for access to European territory for such face-to-face meetings as are still required. But, as indicated, when the threat of offshoring becomes credible, it indirectly affects working conditions and thus local power relations.

In short, there has been an undeniable increase in opportunities for telework in sectors and occupations where it was not previously considered an option. There is an evolution from homeworking to telemigration, which is not necessarily linear and may vary by sector. And while these changes may not presage major job losses, their impact could however be a more general deterioration in working conditions and wages.

Philippe Pochet,former general director of the European Trade Union Institute, is a fellow of the Green European Foundation and an affiliate professor at Sant’Anna College, Pisa.