As the world changes, norms, values and political preferences change. As social risks evolve, so do policy ideas and reforms. The mid-20th century objective of male-breadwinner full employment has, since the momentous entry of women into the labour market from the 1980s, given way to norms of gender equality and equal pay, and policy ideas about improving family services for dual-earner families. Education and care for children cannot be left singularly to dual-earning parents engaged in remunerated employment, just as public healthcare and old-age pensions are today self-evidently accepted. Social insurance, the breakthrough innovation of the modern welfare state, buffers boom-and-bust macroeconomic cycles while mitigating the household poverty which otherwise constrains economic engagement and impedes social mobility. Where individuals can rely on adequate income protection, they are less anxious and freer to make autonomous choices. When, in addition, there is paid parental leave and childcare, working families are also far better off in navigating important transitions in their lives. When adequate social protection and capacity-building public services are both in place, they reinforce prosperity and stable democratic politics.

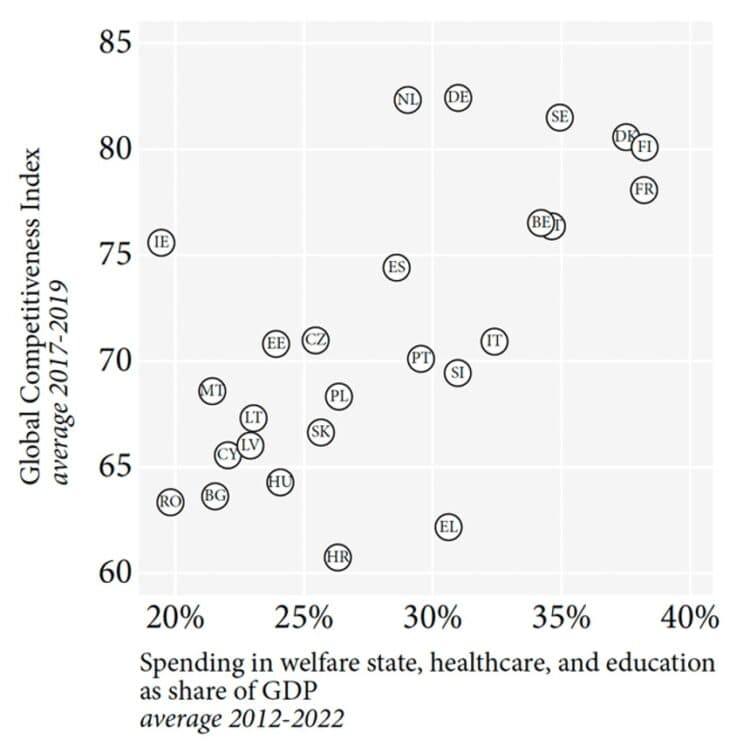

Positive correlation

Europe has since the second world war led the world in engendering such conditions for universal wellbeing through extensive welfare. Yet many now represent—think of the leader of the German Christian Democratic Union, Friedrich Merz—this achievement not as something to celebrate but as an intolerable burden on the taxpayer, particularly in ageing societies with more elderly dependants. There is much talk in Europe of an economic imperative of ‘competitiveness’, vis-à-vis the United States and especially China—though only companies, not countries or regions, compete in markets—with the implication that social expenditures (and indeed ecological regulations amid onrushing climate catastrophe) must be subjected to hard-nosed paring.

In fact, however, far from being a drag on economic performance, for welfare states the opposite is the case: there is a positive correlation between welfare expenditure and per capita gross domestic product, with the universal Nordic welfare states and the developed social-insurance models of mainland northern Europe in the van in both cases (see figure). What makes the difference is that high social investment in each citizen—from quality childcare through to comprehensive public education to post-school education or training for all and lifelong learning—allows people to develop their capacities and effectively use them throughout their lives.

Social spending and competitiveness

This shows that there is no inherent tension between equity and efficiency. On the contrary: without gender equality and supportive family services, for example, there will be less (female) employment and poorer schooling, which in turn will hamper long-term prosperity. Productivity only becomes meaningful when attached to the freedom to navigate life-course transitions.

Reaping rewards

Rethinking welfare in these social-investment terms shows that clawing back expenditure today will be costly tomorrow. Even more, it demonstrates that a generous commitment to welfare expenditure can reap social as well as economic rewards. It directs policy-makers to privilege programmes which are ‘upstream’ (such as preventative public-health schemes like free vaccination for all) over those which are ‘downstream’, focused on compensation ex-post. And it highlights where synergies may be achieved: for instance, a ‘housing first’ approach to homelessness can be followed up by individualised support with associated disadvantages, such as addictions. Vicious circles of accumulating disadvantage can thus be broken at the root of what causes intergeneraitonal cycle of poverty, allowing previously marginalised individuals to finally exercise their agency.

Indeed the reorientation towards investment in individuals’ capacities is particularly attuned to various social risks emerging with an era of digitalisation and precarisation, especially in the ‘gig’ economy. By focusing not only on compensation for income loss—however important as a bedrock this remains—the social-investment perspective adduces important policy interventions, such as in universal access of young workers to training for professional sovereignty.

The European Union should articulate, steer and consolidate this changing social outlook. The European Commission and the European Parliament have adopted the language of social investment over the last decade. This has however largely been in technocratic-instrumental terms—as a policy strategy to achieve and sustain high levels of employment, needed to finance the fiscal ageing burden. It’s high time to reinforce this argument in more normative terms, to bring it closer to real lives in European societies.

Strengthening agency

As our societies change so do welfare states, but also normative thinking on what constitutes social justice. Many philosophers, including Amartya Sen and Martha Nussbaum, have made important contributions to a shifting understanding of justice from a narrow focus on redistribution to a more contextualised and gender-sensitive approach that focuses on real opportunities people have—beyond income—to achieve wellbeing and increased agency.

In policy terms, the social risk structure of post-industrial societies requires both direct protection through social insurance and equipping with the right capabilities through ex-ante prevention, to allow citizens to overcome accumulating disadvantages and lead good and self-determined lives. The combination of protection and capacitation aims to strengthen an individual’s agency in this process and enable them to translate opportunities into secure conditions of wellbeing.

Safety nets protect people from material deprivation, but they also foster active agency since a sense of security allows people to navigate and plan their lives against the backdrop of rapid social change, volatile labour markets and fluid family structures. Capacitation, complementing social protection in core areas of health, education, and family, aims to enable and promote one’s capabilities and hence to securely sustain core areas of wellbeing —for example, through childcare, work-family reconciliation and lifelong learning.

The European Pillar of Social Rights can only be taken off the page and its targets on poverty reduction and training participation realised if the associated social policies are put into effect. The second action plan for the pillar, due to appear in the second half of next year, can provide a focus for enhanced commitment to social-investment welfarism.

This article is part of the Project “EU Forward” Social Europe runs in cooperation with the Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung.