The ‘digital euro’ has become the prestige project of the European Central Bank. In the words of the ECB president, Christine Lagarde, ‘the digital euro is not a stand-alone project, confined to the payment domain. It is rather a cross-policy and truly European initiative that has the potential to affect society as a whole.’

But so far it is difficult to see how the digital euro will be institutionally designed and what its business model will comprise. (Even the term is misleading, since a ‘digital euro’ of sorts has existed since the introduction of the single currency in 1999, in the form of bank deposits denominated in euro—only with the introduction of euro cash in 2002 was the euro also physically available.)

Put simply, there are two design options. The ECB could create a new payment object, which could be used in existing payment systems such as credit cards and Paypal; European citizens would be able to open a digital-euro account with the ECB. More ambitiously, it could establish a new payment system, in which payments would be made using digital euro. The choice is akin to developing a new car to drive on existing highway networks or establishing a new network for the new car, which would then compete with existing networks.

It is obvious that the ECB wants to create a new payment object. Fabio Panetta, a member of its executive board, speaks of ‘a means of payment that could be used for any digital payment’. Panetta explains the need for the digital euro thus:

[W]e need to preserve the role of public money as the anchor of the payments system in order to ensure the smooth coexistence, the convertibility and the complementarity of the various forms that money takes. A strong anchor is needed to protect the singleness of money, monetary sovereignty and the integrity of the financial system.

In the view of Lagarde this anchor function requires ‘that citizens can convert private for public money at par, which ensures that all forms of money can be used indiscriminately for payments throughout the economy’.

Anchor of stability?

While it is true that the credibility of commercial bank systems relies on the ability to exchange deposits without limit with central-bank money, the ECB’s plans do not meet this requirement. So far, it wants to restrict individual holdings of the digital euro to a very low level: under discussion is a limit of only €3,000. That would be a far cry from the ECB’s claim to create an anchor of stability with the digital euro, by guaranteeing the exchange of bank deposits at par with central-bank money.

Such a low limit would also eliminate the potential advantage of a deposit held directly with the central bank. While a central-bank deposit is an absolutely safe asset, commercial bank deposits up to €100,000 have that quality too, as their holders are protected by the deposit insurance guaranteed by their national government.

But the digital euro should not only be discussed as an alternative to a deposit at a commercial bank. In the view of the ECB its main rationale is providing a digital alternative to cash. Seen from this perspective, a better name for it would be ‘digital cash’.

This however immediately highlights the problem that such a design combines features which in the eyes of most consumers are mutually exclusive. One could say that digital cash would be as unattractive as alcohol-free wine: just as wine drinkers like wine because of the alcohol, most users of cash use it as a means of payment and store of value precisely because it is physical.

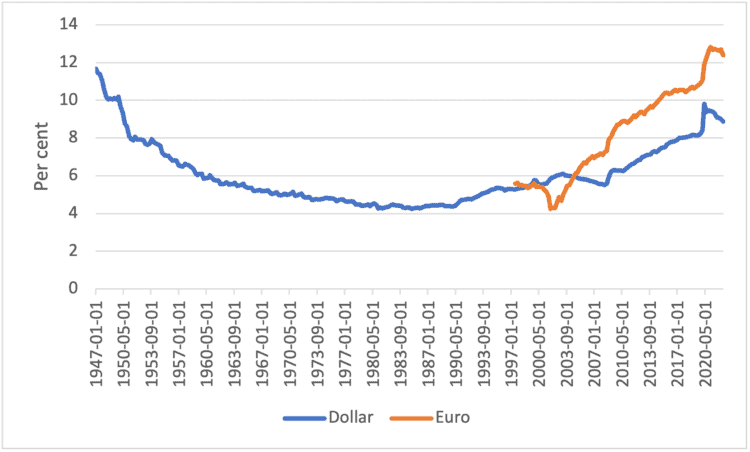

This preference for a physical means of payment is reflected in the fact that circulation of cash relative to nominal gross domestic product has been rising for decades in the United States and, latterly, the euro area, despite the impressive technological advances in retail payments (figure 1). The argument of the ECB that ‘public money could ultimately lose its role as the monetary anchor’ is not so far supported by the evidence.

Figure 1: currency holdings as a proportion of GDP (%)

Thus, the digital euro project must go beyond simply providing a new payments object. Would it not be a good idea to develop a European payment system competing with the dominant US platforms? In fact, the latter is purportedly one of the key objectives the ECB says it wants to achieve with the digital euro: ‘A digital euro would also strengthen the monetary sovereignty of the euro area and foster competition and efficiency in the European payment sector.’

The analogy of the highway shows that successful payment systems have the advantage that a wide variety of cars can be driven there. Paypal, for instance, permits payments with different objects and instruments: deposits held at commercial banks in different jurisdictions with (26) different currencies; credit cards as payment instrument, which draw on deposits held with commercial banks as payment objects; crypotcurrencies, and deposits held directly with Paypal.

High profits

According to the information available so far, the ECB seems to envisage a payment system in which one can only pay with a deposit in the form of the digital euro. What could make such a system prevail over Paypal, credit cards and so on? One argument proferred again and again is that it could process payments at more favourable conditions than the US platforms, which indeed make high profits.

But price is not the only feature that matters when it comes to use of payment systems. Consumers in eurozone member states already have the option of using low-cost payment systems for simple transactions.

For instance, in Germany, the Girocard provided by the banking system is a low-cost instrument which is already more widely used than cash. Transaction costs are in the range of 0.14 to 0.17 per cent. Thus, there is no obvious need for the ECB as a provider of cheap digital retail payments, which would require the parallel holding of digital-euro deposits.

Therefore, the challenge is to establish a European payment system like Paypal, open to different payment objects and instruments. It must offer, in addition to the basic payment transaction, a broad range of services for retailers and consumers, especially for online trade. But running such a comprehensive payment system goes beyond the remit and scope of a central bank.

All in all, the digital-euro project is wrongly conceived. There is neither a need for central-bank deposits limited to a few thousand euro nor a need for a new payment system—based on a digital euro—merely to make cheap digital payments while offering no additional services. If the ECB does not fundamentally rethink the concept, it runs the risk that the digital euro will be a flop. This would do considerable damage to the bank’s reputation.

Successful project

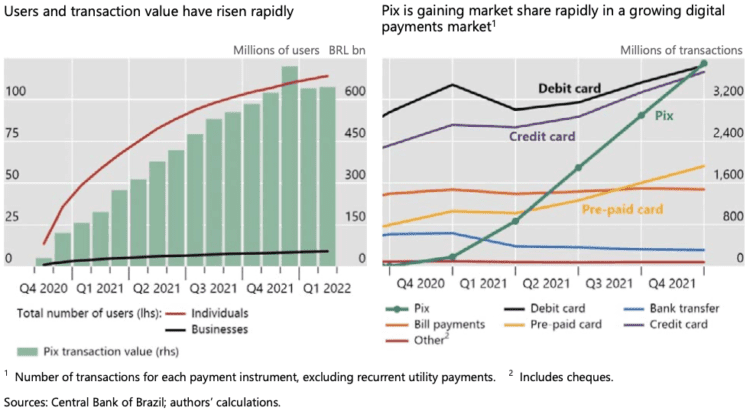

Is there a way out of this impasse? A very successful project is the Pix system, introduced by the Banco de Brazil in 2020. Under it, the central bank provides a settlement system for retail payments which can be used with a wide variety of payment instruments.

The big difference from the digital euro is that with Pix households and companies can use their existing bank deposits as payment objects—there is no need to hold any deposit with the central bank. Therefore, the PIX system does not provide a central-bank digital currency.

To stay with the highway analogy, in Pix, the central bank, together with the banks and other payment service providers, has established an attractive new network which can be used with all kinds of vehicles. A new vehicle developed by the central bank is not required.

As data from the Bank for International Settlements show, it is an impressive success (figure 2): ‘By end-February 2022 (15 months after launch), 114 million individuals, or 67% of the Brazilian adult population, had either made or received a Pix transaction. Moreover, 9.1 million companies have signed up—fully 60% of firms with a relationship in the national financial system.’

Figure 2: usage and market share of the Pix payments system in Brazil

In sum, while there is an urgent need to develop a competitive European payment system, the idea that it must be based on a digital euro is fundamentally flawed. The ECB should observe the ‘first law of holes’ conceived by the the one-time British Labour finance minister Denis Healey: when you are in one, stop digging.

This is a joint publication by Social Europe and IPS-Journal

Peter Bofinger is professor of economics at Würzburg University and a former member of the German Council of Economic Experts.