Giving the public impression that inflation is ‘too low’, Peter Bofinger writes, is not a good look for the bank.

As never before in its history, the European Central Bank is now called upon to promote its policy among the public. In the face of the sharp recent rise in inflation, it is hard even for journalists and many economists to understand why the ECB, for the time being, is sticking to negative interest rates and extensive asset purchases—even though it should.

While it is not an easy task to explain this seeming contradiction, the ECB should try to justify policy decisions as effectively as it can. Indeed, in its strategy review the bank explicitly recognised the importance of communication:

The importance of monetary policy communication has increased significantly over time. Monetary policy communication has become a monetary policy tool in itself, with forward guidance being a prominent example. The better monetary policy is understood, not only by experts but also by the general public, the more effective it will be.

Anyone who followed the ECB’s press conference on December 16th would however be hard pressed to conclude that this particular communication was crowned with success.

Little of substance

The ECB should have explained why it is wrong to project temporary price rises as enduring high inflation. But in its ‘monetary policy statement’, supposed to ‘set out a narrative motivating the policy decision’, this prevailing fear was not addressed at all. In response to a question from a journalist, the bank’s president, Christine Lagarde, could offer little of substance, apart from the comment that wage developments—in an orthodox view, the cause of the last period of high inflation in the 1970s—were being examined very carefully.

The crucial communication problem is that the ECB has a very different ‘narrative’ in mind than the public. While the public fears that inflation will be too high over the medium term, as Lagarde’s remarks make clear the ECB’s concern is that inflation will be too low. This concern is formulated quite explicitly in the monetary policy statement: ‘The inflation outlook has been revised up, but inflation is still projected to settle below our two per cent target over the projection horizon.’

Since ECB staff forecast inflation of 1.8 per cent in 2024, the question immediately arises—and it was put to Lagarde—whether this small difference can be regarded as a missed target. She replied:

So in relation to our inflation projections for 2023 and 2024, which are at 1.8 per cent respectively, a small 1.8 per cent, and a slightly higher 1.8 per cent for ’24, we are really making progress towards target. Are we at target, given that our target is 2 per cent over the medium-term, and looking at the three criteria of our forward guidance? Not quite.

But this puts the ECB on shaky ground. Could one really justify its very expansionary policy stance, with its strong, real-economy and financial side-effects, by a deviation in 2024 of less than 0.2 percentage points from the inflation target? Given the considerable uncertainties of a forecast so far ahead, this does not carry conviction.

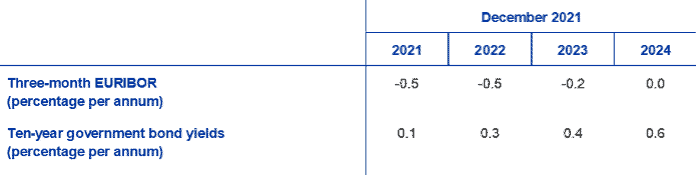

How can the ECB get out of this mess? It should take a closer look at the assumptions of its own projections, prepared by its staff and those of national central banks. For the development of interest rates, market expectations, short- and long-term, are assumed. As the table shows, market participants expect that short-term interest rates will remain negative until 2023 and long-term interest rates will not rise significantly either.

Thus the inflation forcecast of 1.8 per cent for 2024 is conditioned on the assumption that the ECB will maintain its very expansionary policy. A premature tightening would then lead to an inflation rate well below that.

To justify its policy, the ECB therefore does not need to invoke the minor deviation between 1.8 and 2.0 per cent. Instead, it can argue that a much lower inflation rate—with negative implications for the real economy—would have to be expected if monetary policy were to be tightened at an early stage.

Straitened circumstances

Presenting an inflation rate of 1.8 per cent as too low does not chime well with the public in such straitened circumstances. Instead, the ECB could say that the current course is helping to achieve a price trend in the medium term which is compatible with its mandate.

With this, however, the ECB’s so-called forward guidance is anything but congruent. The monetary policy statement declares:

[T]he Governing Council expects the key ECB interest rates to remain at their present or lower levels until it sees inflation reaching 2 per cent well ahead of the end of its projection horizon and durably for the rest of the projection horizon, and it judges that realised progress in underlying inflation is sufficiently advanced to be consistent with inflation stabilising at 2 per cent over the medium term.

Thus, the ECB is saying that it does want to raise interest rates if inflation reaches 2 per cent sustainably well before the end of 2024 and if the core inflation rate corresponds to 2 per cent in the medium term. This could easily backfire.

Let us assume that inflation in 2024 were forecast to be 2.0 per cent. Since it is already higher, well before the end of the period, the conditions for an interest-rate hike would then be given, according to the forward guidance. Yet exactly the opposite would be advisable: as the forecast makes clear, it is with the given interest-rate path that the inflation target would be perfectly attained. The time for a more restrictive policy has only come when the given interest-rate path results in an inflation forecast of over 2 per cent.

Greatest challenge

The ECB’s confusion highlights its failure to address in detail the concept of inflation targeting, for which interest-rate forecasts are central, in its strategy review. The bank is currently facing the greatest challenge to its credibility. It is high time that it stopped giving the extremely negative impression that expansionary policy is necessary because inflation is still too low in the medium term.

Properly understood and applied, the concept of inflation targeting should be able to convey to the public that the current policy stance can keep inflation under control in the medium term, despite short-term volatility.

This is a joint publication by Social Europe and IPS-Journal

Peter Bofinger is professor of economics at Würzburg University and a former member of the German Council of Economic Experts.