In June the European Commission published a further consultation paper on possible measures to introduce fair minimum wages in the European Union. The commission thereby launched the second phase of an official consultation of European trade unions and employers’ organisations, ending this month, with a view to presenting a proposal for a legal instrument in the autumn. It remains open, however, what exactly the commission means by ‘fair minimum wages’ and how they can be guaranteed.

After years of political discussion, the central question is no longer whether a European minimum-wage regulation will be introduced but in what form: a non-binding recommendation, a binding directive or a combination. Otherwise, the discussion focuses mainly on the level of the minimum wage, its scope (given numerous national exceptions), the procedures and criteria for its regular adjustment, and the involvement of trade unions and employers’ associations in setting it.

The commission’s objective is to develop common European standards on all these points. In view of the great differences across Europe, however, the commission is explicitly not seeking to introduce a single European minimum wage, nor to harmonise existing minimum-wage regimes.

In concrete terms, this means that countries in which minimum wages are set by collective agreements, such as Austria and the Nordic countries—Denmark, Finland and Sweden—as well as Italy and Cyprus, will not be forced to introduce a statutory minimum. The basic idea is to define common criteria for fair minimum wages at European level, implemented at national level according to prevailing customs and practices. The challenge then lies in defining the criteria for an appropriate minimum wage.

Decent standard

In its paper, the commission says simply that the minimum wage should provide a decent standard of living. As a pragmatic approach, the Kaitz index has become the accepted benchmark in political debate. The index is a measure of the relative value of the minimum wage in relation to the national wage structure.

Accordingly, a minimum wage is considered adequate when it is at least 60 per cent of the national median. By analogy with poverty research, a minimum wage of 60 per cent of the median wage is the wage that enables a single full-time worker to avoid a life in poverty, regardless of living and household circumstances, without relying on state transfers.

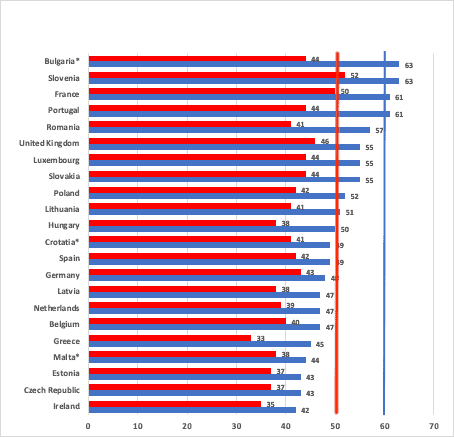

In 2019 the statutory minimum wage met this standard in only four EU member states: Bulgaria, Slovenia, France and Portugal. In all others with a statutory minimum, as well as the United Kingdom, the minimum wage was below—in some cases well below—this threshold (Figure 1).

Figure 1: minimum wage as % of full-time median (blue) and average (red) wages (2019

In countries with collectively agreed minimum wages, the Kaitz index can only be determined approximately, by comparing the lowest wage in a collective agreement with the national median. Against this background, the highest minimum wages are found in Denmark and Sweden, where the lowest collectively agreed wages in the low-wage sectors are between 60 and 70 per cent of the median. In Finland and Italy, the lowest collectively agreed wages vary between 50 and 60 per cent of the median, while in Cyprus they are generally below 50 per cent. In Austria, the minimum wage of €1,500 in 2018, which is no longer undercut in most collective agreements, was 49.5 per cent of the median.

Additional criteria

Yet attaining the 60 per cent median threshold does not ensure that a minimum wage provides an adequate standard of living. In Bulgaria, Portugal and Romania the comparatively high Kaitz indices do not reflect adequate minima as much as poor wages overall. These countries have very polarised wage structures (the top pulling up the average wage) with high concentrations of employees at the lower end of the spectrum (pulling down the median). Additional criteria for setting a fair minimum wage are thus needed.

Particularly in central- and eastern-European countries, it is customary—including among trade union and political advocates—to use the average wage as the reference value for the minimum. A European regulation which used both the median and the average wage as benchmarks for the adequacy of minimum wages would therefore be much more in line with political realities in the EU, while integrating the various national initiatives for a substantial minimum-wage increase into an overall European strategy.

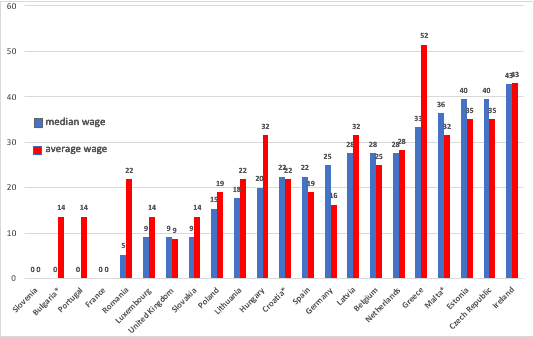

The European standard for the adequacy of minimum wages would then become surpassing both thresholds—60 per cent of the median wage and 50 per cent of the average. Figure 2 shows by how much the minimum wage in various countries would have to rise to reach the respective floors. Application of the double, 60-50 threshold would lead to an increase—sometimes considerable—in the minimum wage in all EU countries with a statutory minimum, except Slovenia and France. In 12 countries the median threshold and in six the mean would have the greater impact; in four the outcome would be the same. The double 60-50 threshold would thus contribute to a general upward convergence of minimum wages across Europe.

Figure 2: increases (%) in the minimum wage needed to reach 60% of the median and 50% of the average (2019)

Real-life test

This however still leaves unresolved the fundamental problem that in countries with low wages overall—as a result of low collective-bargaining coverage, say—even a minimum wage which meets both thresholds may not be sufficient to ensure a decent standard of living. Minimum wages calculated on the basis of the double threshold should thus be subjected to a real-life test—for instance by using a country-specific basket of goods and services, defined with the full involvement of trade unions and employers’ organisations—as to whether they secure a decent standard.

The overall categories of the elements to be included in the basket of goods and services should also be defined in a European framework directive. This finally should include measures to strengthen collective bargaining, to raise the general wage level, with the buttress of binding legal implementation a directive provides.