Global climate commitments will not amount to much without the institutional foundation the transition to a zero-carbon economy needs.

At the United Nations Climate Change Conference in Glasgow (COP26), I joined a panel with leading national politicians, including the Scottish first minister, Nicola Sturgeon, and the Spanish minister for the ecological transition, Teresa Ribera, to discuss how we can get serious about the green economy. As the overwhelmingly male world leaders tussled over commitments, postures and pledges—what the Swedish climate activist Greta Thunberg memorably dismissed as more ‘blah, blah, blah’—our all-women panel focused on the substantive question of what new tools and institutions the world will need in order to decarbonise.

After COP26, it is clearer than ever that top-down pledges and policies are not enough. Rather, we need a structural and institutional transformation from the ground up. Our only hope of keeping global warming within ‘safe’ limits (in fact, the agreed target is much safer for some than for others) is to accelerate a green transition with massive, co-ordinated public investment aimed at innovation leaps and an economic paradigm shift.

Just as climate change is a dynamic, non-linear phenomenon proceeding through a series of tipping points—each with its own knock-on effects, making it extremely difficult to predict the pace and scale of change—the process of curtailing or even reversing it relies on tipping points cascading in the other direction. Synergistic leaps in technological innovation and institutional transformation can precipitate positive feedback loops and cumulative multiplier effects.

Innovate and collaborate

That is precisely the aim of what I have called mission-oriented innovation policy. We need to marshal resources and align economic policies around measurable objectives, such as the emergence of new technological innovations and the shaping of new markets. Each mission must be inspirational and catalytic, and require many actors and sectors to innovate and collaborate in new ways—whether for a carbon-neutral city or a plastic-free ocean. Each mission must crowd in investments by many actors, with strong conditionalities attached to any form of public support, so as to drive the ‘upward-scaling tipping cascades’ that will expand the current technological horizon and usher in a zero-carbon future. But to reorient the economy around mission-oriented innovation leaps, we will need new institutions at all levels, from local to global.

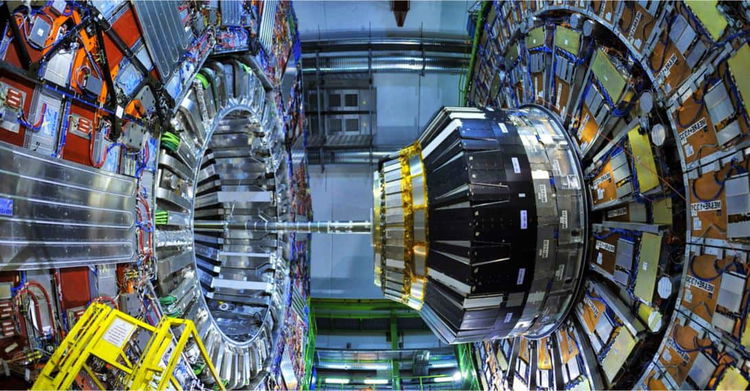

At the international level, for example, a ‘CERN for climate technology’ (modelled on the European supranational scientific research body) can co-ordinate investments from participating governments, using a collective pot to finance the development of innovative technologies that the private sector will not pursue on its own, either because they are too risky or because the financial returns are too low. This idea was featured in the final report of the G7 Panel on Economic Resilience, on which I represented Italy.

At the national level, public green investment banks can provide the patient capital needed to expand zero-carbon markets. A promising model is the Scottish National Investment Bank (which I had the honor of helping set up), a public financial institution whose primary mission is to help decarbonise Scotland’s economy. The new bank will catalyse investment across sectors and firms that are specialising in zero-carbon technologies.

Last but certainly not least is the municipal level, which is where climate action materialises in tangible projects such as zero-carbon housing, car-free neighbourhoods and circular supply chains. Here, the new Council of Urban Initiatives, co-hosted by University College London, the London School of Economics and UN Habitat, has a critical role to play in sharing information about successful projects and aligning them with international agreements, not least those coming out of COP26.

Engagement from citizens

These institutions will need buy-in and engagement from citizens—and especially from vulnerable workers—to get off the ground. The gilets jaunes (yellow vests) and other backlash protest movements have demonstrated why momentum behind the green transition must come from below. The thinking behind Green New Deal proposals is to harness popular energies by putting people at the heart of the economic transition.

Popular participation means engaging citizens in community-level processes, such as the Camden Renewal Commission, which has used key debates among residents’ associations to place housing estates at the centre of the London borough’s clean-growth strategy. It also means inviting community associations, co-operatives and trade unions to form ‘public-common partnerships’ with governments. Another option is to establish citizens’ assemblies on climate change, as Spain has done. Such institutional innovations will serve as the foundation for a new social contract, which is the only way to build public trust and achieve a socially just transition.

The biggest mistake of climate activism has been the failure to make a compelling, realistic case for a green transition that promotes the interests of labour. A Green New Deal that creates good new jobs, raises living standards and reduces precarity and inequality should be the highest priority. The green transition’s success will hinge on measures ensuring that workers whose jobs are threatened by decarbonisation can gain skills and employment in the new economy. Barring that, they should be afforded a guaranteed minimum income as a basic right.

That will not happen unless workers have a place at the negotiating table. Whatever new pledges COP26 has brought about on the global stage, we will need to redouble the behind-the-scenes work of institution-building, with special emphasis on widening participation to include ordinary citizens. Averting a climate disaster will require widespread experimentation with new technologies—and, no less importantly, with new institutions at all levels.

Republication forbidden—copyright Project Syndicate 2021, ‘The right institutions for the climate transition’

Mariana Mazzucato is professor in the economics of innovation and public value at University College London, founding director of the UCL Institute for Innovation and Public Purpose and a co-chair of the Global Commission on the Economics of Water.