After the collapse induced by travel restrictions and closures to counter Covid-19, tourists are arriving in southern Europe in pre-pandemic numbers. It is hard to overstate the economic importance of the recovery of tourism for the region. Yet while it certainly contributes to growth and employment, southern Europe’s excessive reliance on tourism exports comes with important pitfalls.

Despite some differences, Greece, Italy, Spain and Portugal entered the euro in the late 1990s with key similarities in the institutions underpinning their economic model: dualised labour markets and welfare states, weak education and vocational-training systems, adversarial and fragmented industrial relations, inflationary wage-setting systems and political clientelism. Unsurprisingly, these countries’ production strategies were largely based on price competitiveness, backed by competitive currency devaluations, while the state historically played an active role in domestic demand management through public budgets and industrial policy to govern the economy and support domestic firms.

The southern-European economic model was challenged by the deepening of European integration. On one hand, stricter enforcement of European Union competition law and state-aid regulations in the single market forbade states’ economic activism. On the other hand, economic and monetary union (EMU) prevented exchange-rate adjustments while fiscal regulations limited the room for counter-cyclical demand management.

By the 2000s, southern-European economies were thus caught between a rock and a hard place. They lacked the institutional preconditions to excel in the knowledge economy while being too expensive and overly regulated to compete with the newly industrialised economies (such as China) in the production of basic manufactured goods.

Expansion fostered

European integration, however, also fostered expansion of the tourism industry. Europeanisation gradually institutionalised the free movement of Europeans across the union. It forced the liberalisation of highly-protected and state-monopolised national aviation markets, leading to the Single European Aviation Market. These regulatory changes permitted an unprecedented expansion of the tourism industry, allowing European tourists to reach ever more destinations at lower prices through mushrooming low-cost airlines.

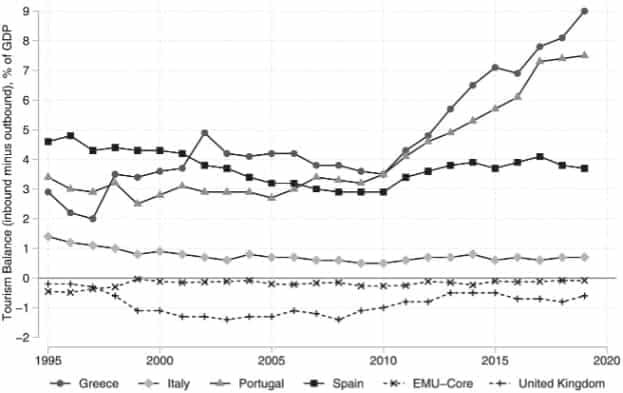

Since the 2008 financial crisis, southern Europe has witnessed hitherto-unknown tourism-led growth—exemplified by the steep rise of related surpluses on the current account as a ratio of gross domestic product (Figure 1). With domestic consumption strangled by austerity and wage cuts, these governments started to look for new strategies to engineer growth and employment through exports. Thanks to southern Europe’s comparative advantagein tourism—ensured by climatic, cultural and geographical conditions—export-led growth in the EMU eventually came through the export of tourism services to northern-European and British travellers, happy to crowd the south’s beaches, hotels and restaurants.

Figure 1: current-account balance for international tourism services (% GDP)

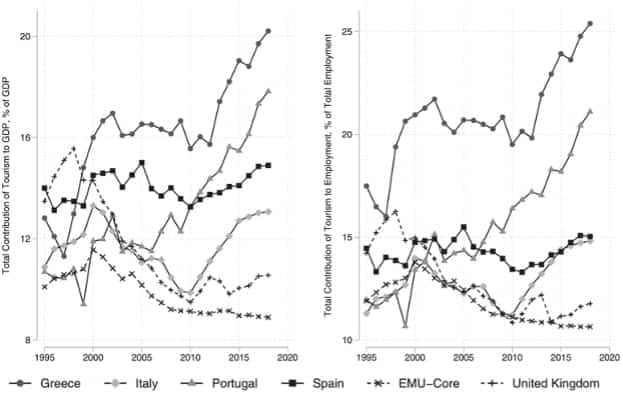

Fast-forward to 2019 and the tourism industry has expanded significantly, constituting a sizeable portion of southern Europe’s exports and a key driver of growth and employment creation (see Figure 2). Tourism-related economic activities account for around 15 to 20 percent of GDP in southern Europe. A quarter of the Greek workforce and a fifth of the Portuguese is employed in undertakings that depend on tourism for their revenues, directly or indirectly. In Italy and Spain around 15 per cent work in a tourism-related company.

Figure 2: total contribution of tourism to GDP (left panel) and employment (right panel)

Our research shows that southern Europe’s unprecedented tourism-related current accounts after 2007 have been funded by a steady rise of inbound tourism from northern Europe and the United Kingdom. Thus the collapse of domestic demand in southern-European economies, due to austerity and internal devaluations, was partly offset by the import of foreign demand for domestic tourism services.

Structural problems

In this respect, tourism-led growth may be a palliative. But it is no cure for the structural problems these economies face in a currency union and in today’s globalised knowledge economy.

First, tourism encourages economic restructuring around low-value-added activities, characterised by low skills, precarious employment and low productivity. While Europe’s northern countries are gradually shifting towards high-skilled, high-value-added manufacturing and high-end services, tourism-led growth leaves southern Europe in a bad equilibrium—trapped between a structural dependency on foreign tourists and a growing vulnerability to exogenous shocks (such as the pandemic).

Secondly, the two-decade expansion of the tourism industry is a global phenomenon. As such, it comes with fierce competition from developing countries, today easily reachable via inexpensive flights. Some of these countries, having comparable natural and cultural riches but lower prices and labour standards, are poised further to undermine employment conditions in the European tourism industry.

Last but not least, the high carbon-dioxide emissions of the tourism industry and the damage to local natural resources brought about by tourism over-exploitation run counter to climate-change mitigation and environmental protection.

Tourism is indeed an opportunity for southern Europe. But conscientious governments in the region should diversify their overall growth strategies to embrace the knowledge economy, while upgrading their tourism offer to make it socially inclusive and environmentally friendly.