The European Parliament elections in June represented a pivotal moment, with a surge of far-right parties in some European Union member states. While this was not universal, with centrist and green parties holding firm and even gaining ground in some countries, there were nevertheless significant advances for Eurocritical parties which stoked public concerns, tapping into years of eroding trust in institutions.

European cohesion, and the fabric of democracy itself, could be threatened in the years ahead. But by working together Europe can restore citizens’ faith in institutions and in the future.

Insidious undertow

Jean Monnet, one of the founding fathers of the union, famously predicted: ‘Europe will be forged in crisis, and will be the sum of the solutions adopted for those crises.’ In recent years, the EU has faced a ‘polycrisis’: the profound shock of the pandemic was followed by the war in Ukraine, the consequent surge in energy and food prices igniting a cost-of-living crisis.

On the surface, the union looks to have weathered the storm well. Yet the strain of the last five years has engendered an insidious undertow of declining trust within its member states.

Trust is the glue that binds us: it is the force of the social contract and the bedrock of democracy. Trust fosters co-operation, strengthens social cohesion, facilitates policy implementation and encourages public engagement and participation. Without trust, societies fall victim to fragmentation, which favours populism and undermines social stability amid geopolitical confrontation.

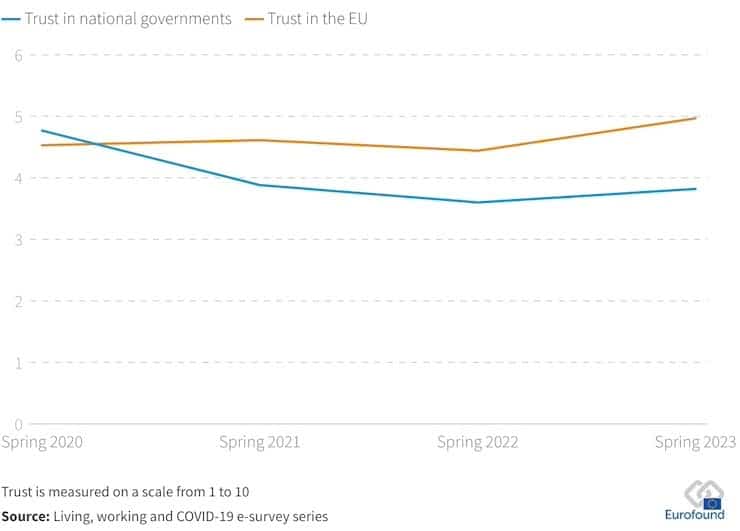

Trust in the EU has actually increased since the onset of the pandemic, yet it remains low. More alarmingly, trust in its member-state governments has decreased (Figure 1).

Figure 1: trust in the EU and member-state governments over time

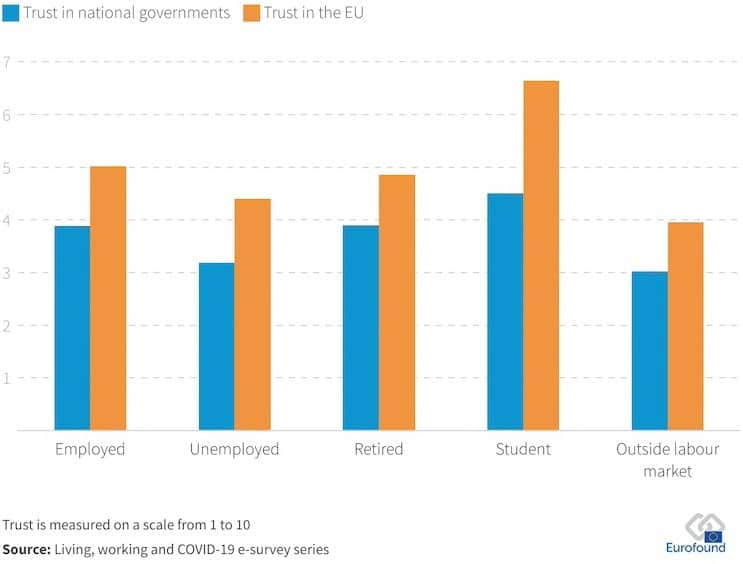

Moreover, trust is unevenly distributed and has decreased unevenly among socio-demographic groups—social fragmentation is a real risk. Trust in both the EU and national governments tends to be higher for students, the employed and retired people but much lower among those unemployed or outside the labour market (Figure 2).

Figure 2: trust disaggregated by social sector

Growing disconnect

The drivers of this erosion of confidence include the cost-of-living crisis, a feeling of being unheard and the divisive power of ‘social media’—all leading to a growing disconnect between citizens and their governments.

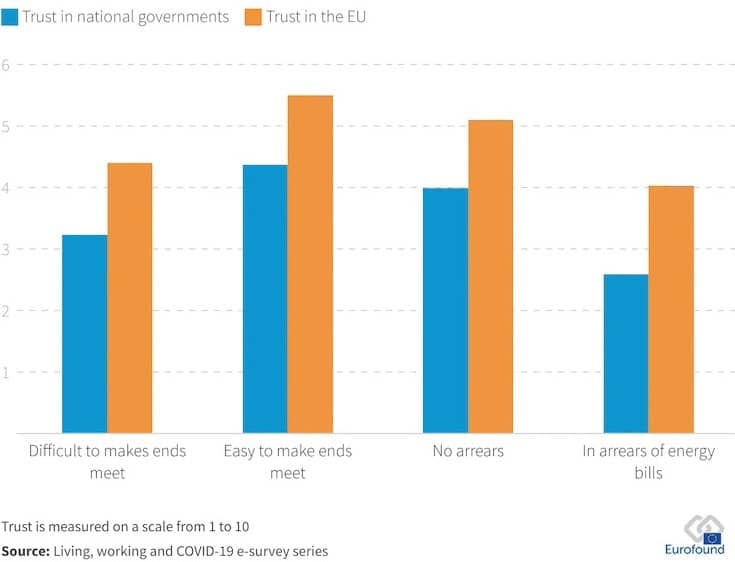

Those more affected by the cost-of-living crisis exhibit much lower trust than others, particularly if struggling to make ends meet or behind with energy bills (Figure 3). Inflation, trailing wages and increased financial strain unravel the fabric of trust in institutions. The cost-of-living crisis chips away at the broader belief that governing bodies have the ability—even the intention—to act in the best interests of their citizens.

Figure 3: trust and social hardship

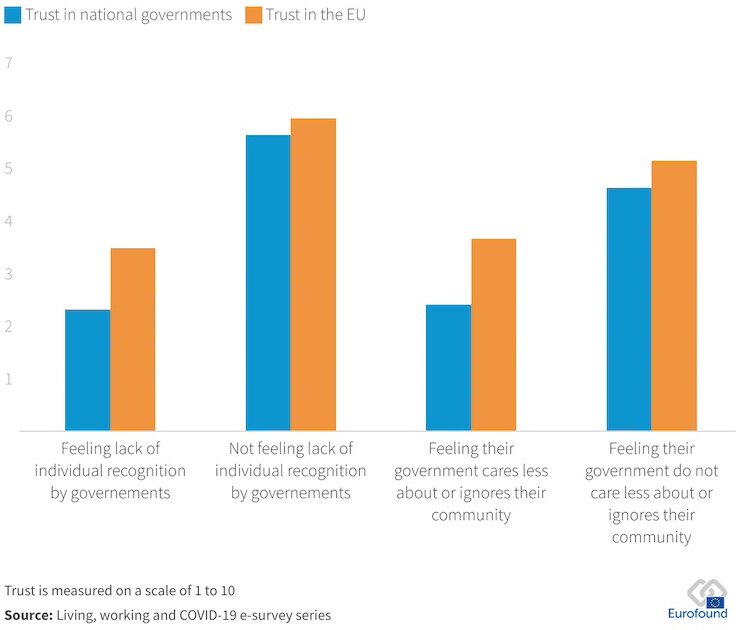

Institutional trust hinges on the belief that citizens’ voices are heard and their concerns acknowledged. Yet many in Europe feel a lack of political recognition (Figure 4), particularly those in rural communities with lower incomes and limited employment opportunities. These people often feel ignored by policy-makers, highlighting rural-urban disparities. This feeling is also common among those outside the labour market and with lower educational attainment.

Figure 4: trust and lack of recognition

This sense of invisibility fosters resentment and fuels discontent, manifesting itself in various forms of protest and demonstration.Growing reliance on ‘social media’ and other non-professional news sources amplifies feelings of exclusion and marginalisation, affecting public discourse and political attitudes.

These virtual spaces can provide fertile ground for the dissemination and validation of polarising, ‘us versus them’ narratives which reinforce a felt lack of recognition, widening the gap between citizens and institutions. Such echo chambers hinder exposure to diverse perspectives and can lead to the demonisation of opposing viewpoints.

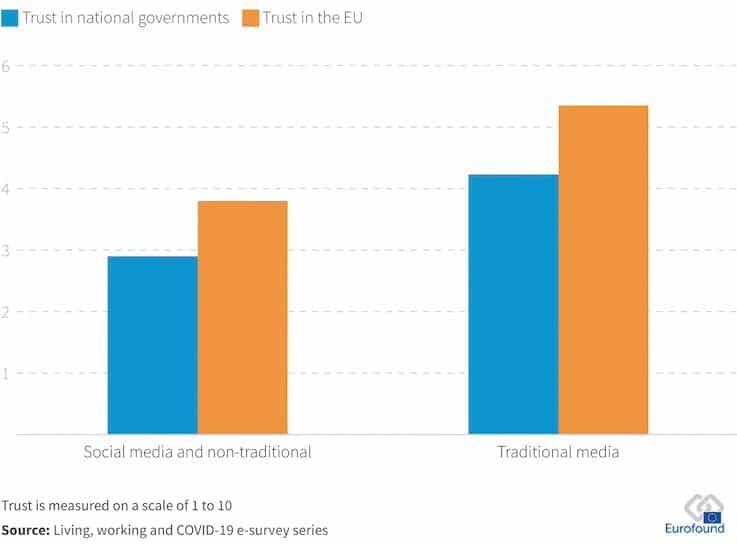

The ease of content creation and dissemination on such platforms facilitates the spread of misinformation—often emotionally charged and sensationalised—which portrays established institutions as corrupt, incompetent or out of touch. Those who rely on ‘social media’ and non-traditional media sources as their main source of information exhibit much lower trust in institutions (Figure 5).

Figure 5: trust and information sources

This fast-paced and often hostile online discourse can hinder constructive dialogue about complex issues and lead to social fragmentation. It makes it difficult for institutions to communicate effectively and address public concerns in a way that fosters trust.

Alarming implications

When citizens lose trust in the institutions that underpin democratic processes, democracy itself loses its legitimacy. The value of participation is undermined and the rule of law thrown into question. The implications are alarming.

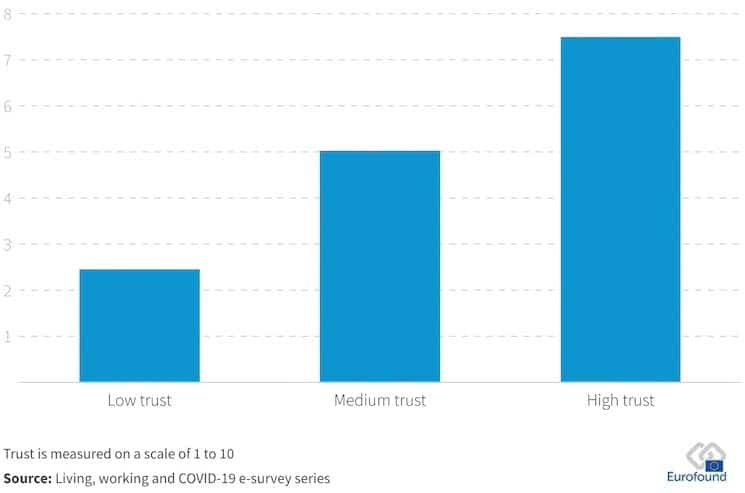

Those with low trust in institutions also exhibit very low rates of satisfaction with democracy (Figure 6). This can lead to a rejection of democratic structures and a yearning for ‘strong leadership’ that bypasses traditional institutions. Weak trust thus favours populist movements and anti-establishment sentiments.

Figure 6: satisfaction with democracy and trust

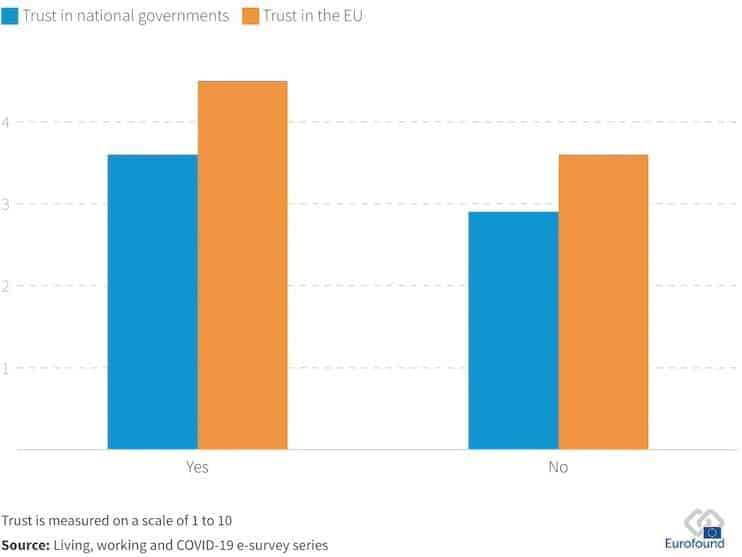

When citizens see institutions as unresponsive or unrepresentative, they may become disengaged from the political process. Decreased voter turnout (Figure 7), a decline in participation in civic activities and general political apathy weaken democratic systems by reducing the pool of active citizens who hold institutions accountable and contribute to a healthy political discourse.

Figure 7: intention to vote and trust

A decline in institutional trust can exacerbate social divisions and fuel polarisation. When citizens lose faith in shared institutions, they may turn inward, reinforcing ingroup identities and vilifying those who hold different views. This hinders dialogue across ideological divides and undermines the ability of democracy to represent the diverse interests in society.

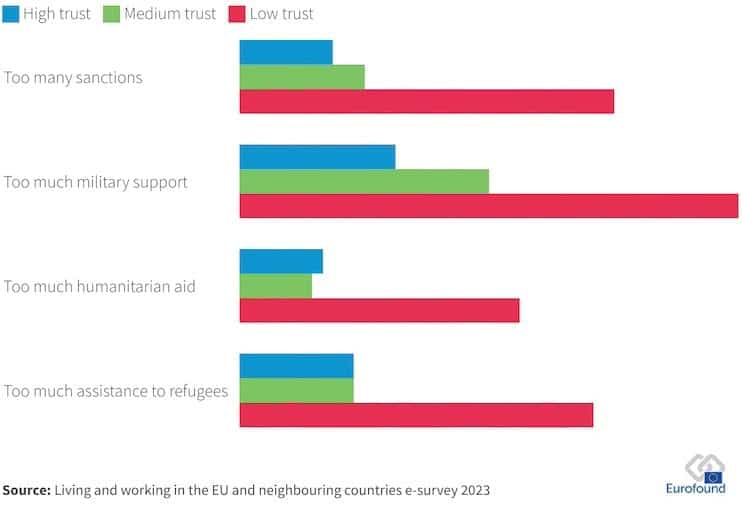

Those with lower trust in institutions are also much less in favour of supporting Ukraine, providing humanitarian aid or assisting refugees (Figure 8). This is of great concern in times of geopolitical tensions, when unity is at a premium.

Figure 8: support for Ukraine and trust in national governments

People with low trust may view additional aid to Ukraine, however necessary, as a distraction from domestic issues such as the cost-of-living crisis. This can fuel a perception that their leaders prioritise ‘foreign’ concerns over their own wellbeing, emboldening populist movements which play on such sentiments.

The share of people with low trust in institutions who believe that there has been too much support for Ukraine—military or humanitarian—is up to five times as great as for those exhibiting higher trust. Almost half of those with low institutional trust believe military support has been excessive, and around a third believe the same of support for refugees. These are disturbing numbers for the future of EU involvement in the crisis and leave the door open for third countries to attempt further to destabilise the union.

Rebuilding trust

Rebuilding trust is crucial for the EU to navigate the challenges it faces and ensure a prosperous and united future for its citizens. Key areas demand attention.

Effective and transparent dialogue: EU institutions and national governments must improve their dialogue and communication with citizens. They should foster open and transparent dialogue, for instance through broader participation in policy-making, actively listening to citizens’ concerns, developing place-based policies, and ensuring clear and consistent messaging on key policies and decisions.

Delivering on promises: the EU needs to demonstrate its effectiveness by delivering on its promises and implementing policies that demonstrably improve the lives of citizens. Ensuring equitable access to essential services, addressing regional inequalities and finding solutions to shared challenges such as people movement and climate change will be crucial in regaining public confidence.

Combating disinformation and manipulation: the fight against the manipulation of information online is crucial. This requires collaboration among governments, ‘social media’ platforms and civil-society organisations to tackle the spread of misinformation and promote responsible online behaviour.

Investing in social cohesion: the EU should prioritise initiatives that enhance social cohesion and bridge the gaps between communities. This includes supporting cultural-exchange programmes, promoting civic engagement and fostering a sense of shared European identity.

The decline in trust in the EU is a complex challenge with no easy solutions. However, by addressing the root causes, encouraging dialogue, delivering on promises and investing in cohesion, the EU can ensure a more united and prosperous future. This requires a collective effort from national governments, the EU institutions and civil society, working together to bridge divides and rebuild faith in the European project.

Massimiliano Mascherini Is head of the social policies unit at Eurofound, having joined the organisation in 2009 as a research manager. He has a PhD in applied statistics from the University of Florence and has been a visiting fellow at the University of Sydney and Aalborg University.