Supporters of a social Europe breathed a collective sigh of relief when the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) delivered its judgement on the Directive for Adequate Minimum Wages in the EU (Case C-19/23) on 11 November 2025. With only minor exceptions, the Court validated the directive and brought an end to a prolonged period of legal uncertainty that had cast a shadow over one of the EU’s most significant social policy initiatives in decades. Various legal observers had argued that the EU lacked the authority to propose such a directive, contending that Article 153(5) of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU) explicitly excludes EU competences on the issue of “pay”.

Following these arguments, the Danish government brought the case before the CJEU in early 2023, seeking to have the entire directive annulled. This position gained significant momentum in January 2025, when the Advocate General to the CJEU issued an opinion that called for a full annulment of the directive, raising serious concerns about the future of this landmark social legislation.

The CJEU judgement validates the directive

The CJEU judgement rejected this reasoning. Instead, it clearly validated the conformity of the directive with EU law, establishing a crucial distinction that will shape future social policy initiatives. The Court took the view that the prohibition of regulation under Article 153(5) TFEU applies only to cases that provide for a direct interference in the determination of pay. Other measures with a more indirect impact on wages remain permissible as instruments for the improvement of working conditions. The Court thus confirmed the directive’s legal basis in Article 153(1b) TFEU, according to which “the Union shall support and complement the activities of the Member States in the (…) fields of (…) working conditions.”

The Court identified only two specific provisions in the directive that constitute direct interference in the national determination of wages and must therefore be annulled. The first is Article 5.2 of the directive, which defined four criteria to be taken into account by member states when setting and updating the statutory minimum wage: the purchasing power of statutory minimum wages, the general level of wages and their distribution, the growth rate of wages, and long-term national productivity levels and development.

According to the judgement, this amounts to harmonisation of some of the constituent elements of statutory minimum wages and, consequently, directly interferes with the determination of pay. The second provision to be annulled is a non-regression clause in Article 5.3, applied to statutory minimum wages that are adjusted using an indexation mechanism.

Crucially, the CJEU confirmed the validity of all the other provisions of the directive. In particular, all the provisions promoting collective bargaining remain intact, such as Article 4.2, which obliges member states to establish an action plan to promote collective bargaining if bargaining coverage falls below 80 per cent. The Court also confirmed Article 5.4 of the directive, which obliges member states to use “indicative reference values” to assess the adequacy of statutory minimum wages and which strongly recommends the use of the “double decency threshold” of 60 per cent of the national gross median wage and 50 per cent of the gross average wage.

The annulments will have little practical impact

The practical implications of the two annulments are remarkably limited when examined closely. With respect to the criteria to be taken into account when setting or updating statutory minimum wages, most member states had simply added the four criteria set out in Article 5.2 to existing lists of criteria when they transposed the directive into national law. Since Article 5.1 of the directive explicitly states that member states “may decide on the relative weight of the criteria” used to set and update the statutory minimum wage, the practical implications of adding the four—now annulled—criteria were limited from the outset.

It therefore seems highly unlikely that member states which introduced the four criteria in the context of transposing the directive will now roll back these criteria as a consequence of the judgement. This applies all the more forcefully to the 11 of 22 EU member states with statutory minimum wages that have signed ILO Convention No. 131 concerning Minimum Wage Fixing, which requires signatories to take into account almost identical criteria when setting minimum wages.

The practical impact of the annulment of the non-regression clause for countries using some kind of indexation mechanism in setting statutory minimum wages can also be expected to remain quite limited. Currently, only four countries use an indexation mechanism: the development of minimum wages is linked to the development of consumer prices in Belgium, France, Luxembourg and Malta. To this group we can add Bulgaria, which applies an indexation formula linked to the development of average wages, and the Netherlands, where minimum wages are linked to the development of collectively agreed wages.

Most importantly, however, in none of these countries has the use of an indexation mechanism ever led to a decrease in minimum wages. In fact, the only instances where statutory minimum wages have been decreased over the past 20 years occurred in Ireland and Greece as a result of the intervention by the Troika during the 2009-2010 financial crisis, circumstances entirely unrelated to indexation mechanisms.

While the practical implications of the partial annulment will remain very limited, the impact of the validated provisions has already been substantial across the European Union. The impact of the directive can be seen in two distinct dimensions: the formal transposition of the directive into national law on the one hand, and the political influence of the directive on the broader discourse about minimum wages and collective bargaining in the member states on the other. In practice, the impact of the directive extends far beyond its formal transposition by bringing issues like the adequacy of minimum wages and the strengthening of collective bargaining onto the political agenda and by providing progressive forces with a powerful tool to push for measures that aim to ensure more adequate minimum wages and stronger collective bargaining systems.

The use of reference values for statutory minimum wages

As a forthcoming ETUI study demonstrates, the use of reference values has had the most far-reaching impact on national minimum wage-setting processes. In some countries, particularly Bulgaria and Croatia, this contributed to substantial minimum wage increases over the past two years. Of the 22 member states with a statutory minimum wage, 17 now use some kind of reference value to set the minimum wage and to assess its adequacy (see Table 1). Member states retain the freedom to choose the concrete type and level of the reference values. Almost all countries use the Kaitz Index, which measures the minimum wage as a percentage of the average and/or median wage, as the reference value. Slovenia stands as the only exception, using minimum living costs instead.

With respect to the level of the reference value, most member states use the indicative reference values of 60 per cent of the gross median and 50 per cent of the gross average wage, as recommended in Article 5.4 of the directive. In five countries (Czechia, Latvia, Lithuania, Netherlands (proposed) and Romania), the reference value is slightly lower, while in Poland, Slovakia and Spain it is higher than the level recommended in the directive. However, even the use of the lower reference value represents an improvement compared to the current level in the respective countries. Since the legality of Article 5.4 of the directive has been expressly confirmed by the CJEU, the use of reference values for setting statutory minimum wages is likely to become even more important and widespread in the future.

Table 1: Indicative reference values used by EU member states for setting statutory minimum wages

| Country | Reference value | Country | Reference value |

| Belgium | 50% of average wage | Latvia | 46% of average wage |

| Bulgaria | 50% of average wage | Lithuania | 45-50% of average wage |

| Croatia | 50% of average and 60% of median wage | Netherlands | 50% of median wage (proposal) |

| Czechia | 47% of average wage (by 2027) | Poland | 55% of average wage (draft law) |

| Estonia | 50% of average wage (by 2028) | Romania | 47-52% of average wage |

| France | 50% of net average and 60% of net median wage | Slovakia | 60% of average wage |

| Germany | 60% of median wage | Slovenia | 120-140% of minimum living costs |

| Hungary | 50% of average wage (by 2027) | Spain | 60% of average net wage |

| Ireland | 60% of median wage |

Source: ETUI 2025

Impact on collective bargaining

The directive has also already shaped national developments in collective bargaining in profound ways. So far, five countries (Belgium, Czechia, Malta, Poland and Slovakia) have introduced changes in the legal framework for collective bargaining. These changes mainly concern three critical areas: first, strengthening the protection of workers and trade unionists from discrimination when exercising their right to collective bargaining and to unionise; second, facilitating the conclusion and extension of collective agreements to cover more workers; and third, improving the collection of data and information on collective agreements in order to establish a more sound empirical base for measuring collective bargaining coverage.

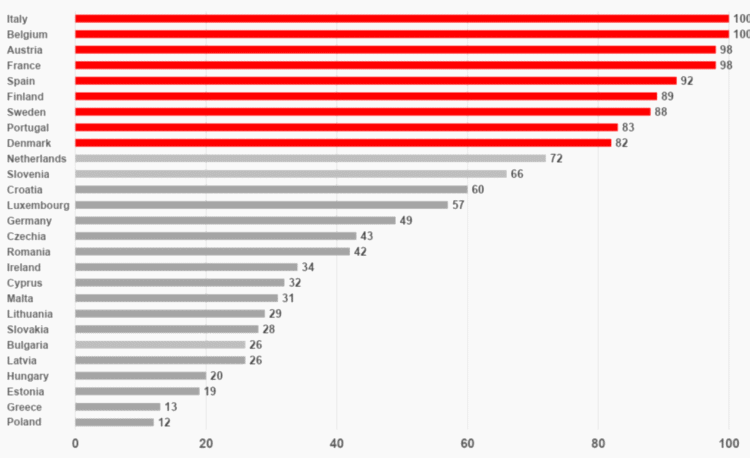

Figure 1: Collective bargaining coverage in EU member states (per cent; 2024 or most recent year available)

Source: OECD/AIAS 2025; for Slovenia: Republic of Slovenia Statistical Office 2025

In line with Article 4.2 of the directive, action plans to promote collective bargaining have already been adopted in Czechia, Estonia, Ireland, Latvia, Lithuania and Romania. The remaining 12 countries that are required to establish an action plan by the end of the year find themselves at different stages of the discussion process. This, however, only concerns the formal transposition and implementation of the directive’s obligations. In a range of countries, significant developments have taken place in the shadow of the directive. In Portugal, Romania and Spain, for example, comprehensive reforms of the collective bargaining system were introduced in 2022 and 2023; this explains why these governments saw no need for further changes in the process of the transposition of the directive.

The ruling will bring new impetus

The validation of the Minimum Wage Directive and its core provisions through the CJEU will provide new impetus to the struggle for adequate minimum wages and strong collective bargaining across Europe. First and foremost, it will put pressure on those countries which still have not transposed the directive to do so as quickly as possible. This is particularly true for those countries—such as Estonia and the Netherlands—where the transposition of the directive was explicitly put on hold pending the CJEU ruling. The decency thresholds of 60 per cent of the median and 50 per cent of the average wage will continue to serve as “the reference parameters for assessing the adequacy of statutory minimum wages” (Recital 99 of the Judgement).

As for the promotion of collective bargaining, the Court’s full approval of Article 4 of the directive means that a further 12 EU member states with a bargaining coverage below 80 per cent will have to establish a national action plan to promote collective bargaining by the end of the year, in addition to the six countries which have already adopted such a plan. In these action plans, the focus should be on the strengthening of sectoral bargaining as the most important precondition for achieving comprehensive bargaining coverage.

All in all, the CJEU judgement represents a clear confirmation of the European Minimum Wage Directive, which from a workers’ perspective has probably been the most important social initiative of the EU in decades. The judgement of the CJEU will provide new energy to the implementation process, thus ensuring that adequate minimum wages and the promotion of collective bargaining will remain firmly on the political agenda at both national and European levels. Therefore, 11 November 2025 was indeed a good day for Social Europe, marking not an end but a new beginning in the struggle for fair wages and strong collective representation across the continent.