One should be careful using the word ‘historic’. But in the case of the directive on adequate minimum wages in the European Union it might actually be appropriate.

On June 16th, EU employment and social-affairs ministers (the EPSCO Council) overwhelming confirmed the outcome of the trilogue among the European Commission, the European Parliament and the Council of the EU—only Denmark and Sweden voted against, while Hungary abstained—on the first ever EU legislation explicitly aiming to ensure adequate minimum wages and strengthen collective bargaining. The directive still needs to be formally approved by the parliament and the council in September, but with EPSCO’s assent the highest hurdle was cleared.

Decency threshold

The objectives of the directive are to ensure adequate minimum wages enabling a decent standard of living, to fight in-work poverty and to reduce wage inequality. Article 5(2) sets out criteria which member states need to consider when setting statutory minimum wages: purchasing power, which takes into account the costs of living; the general level of wages and their distribution; the growth rate of wages, and long-term national productivity levels and trends. These criteria essentially reflect current national practice and member states are free to decide on the relative weight they attach to them.

Perhaps the most important provision, though, is in article 5(3), which says that member states ‘shall use indicative reference values to guide their assessment of adequacy of statutory minimum wages’. It goes on: ‘For that purpose, they may (our emphasis) use indicative reference values commonly used at international level such as 60 per cent of the gross median wage and 50 per cent of the gross average wage.’

The directive thus establishes de facto a double decency threshold. (The proportions are different for the median and the mean because high-end wages pull up the latter but not the former.) While not legally binding, it represents a strong normative benchmark for setting minimum wages at national level. In practice, this threshold already guides minimum-wage setting in various member states.

Germany, for instance, anticipated the adoption of the directive with its decision to increase the statutory minimum wage to €12 by October this year—around 60 per cent of the gross median wage. The Irish government recently announced that the existing statutory minimum wage would be phased out by 2026 and replaced by a new living wage, to be set at 60 per cent of the median. In Belgium, the minister of economy and labour has already recognised that the minimum wage does not meet the new European standard. And in the Netherlands, the trade union federation FNV has called on the government to increase the minimum wage to €14, to fulfil the directive’s requirements.

Far-reaching implications

Since none of the member states with a statutory minimum wage currently fulfils the double decency threshold, however, an increase of minimum wages to this level would have far-reaching implications. According to the commission, some 25 million workers would benefit. Such a structural increase is particularly important in times of high inflation. Furthermore, since women are traditionally over-represented among minimum-wage earners, minimum wages at the double decency threshold would help reduce the gender pay gap.

Another crucial innovation is the recognition of the importance of collective bargaining in ensuring adequate minimum wages. Among the various provisions which seek to strengthen the role of trade unions are the explicit affirmation in article 3(3) that collective bargaining is their prerogative—not that of the more vaguely-formulated ‘workers’ organizations’ in the original text from the commission—and article 4(1), which guarantees the right to collective bargaining and protects workers who engage (or wish to engage) in it from discrimination.

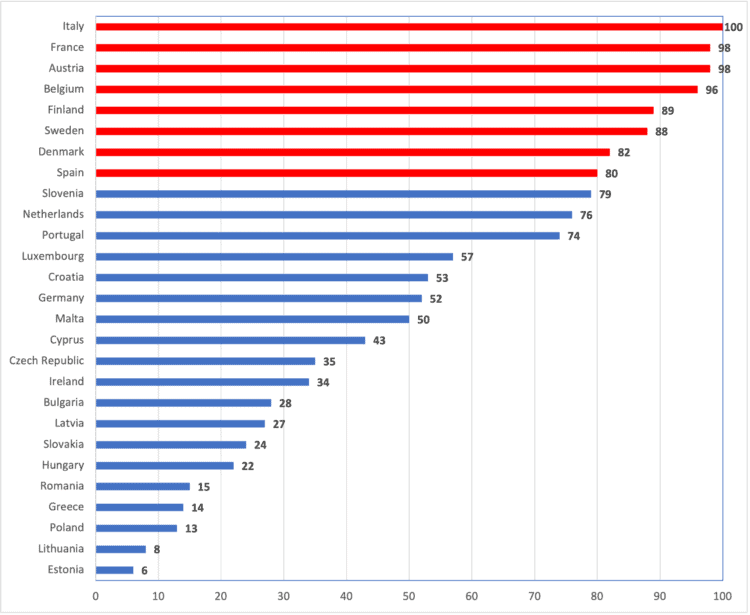

Article 4(2) further obliges member states with less than 80 per cent collective-bargaining coverage to take measures to increase it. This includes national action plans which contain a clear timeline and concrete measures progressively to increase the degree of coverage. These plans are to be developed in co-operation with the social partners, regularly reviewed and updated at least every five years.

As the graph illustrates, only six countries currently fulfil this threshold. In all of them collective bargaining is primarily conducted at the sectoral level. The 80 per cent threshold can therefore be seen as an implicit call to promote sectoral bargaining.

Collective-bargaining coverage in the EU (2019 or most recent year available)

Paradigm shift

The directive’s objectives to ensure adequate minimum wages that provide for a decent standard of living and to strengthen collective bargaining represents a paradigm shift in the European institutions’ view of wages and collective bargaining, compared with the policies pursued in the eurozone crisis. Exactly ten years ago, the Directorate-General for Economic and Financial Affairs (DG ECFIN) recommended a decrease in statutory minimum wages and collective bargaining coverage and an overall reduction of trade unions’ wage-setting power, as ‘employment-friendly’ reforms—illustrating how far the commission has come.

Adequate minimum wages and strong collective bargaining are no longer seen as part of the problem but part of the solution. The minimum-wage directive provides a safeguard against any further attempts to dismantle national bargaining systems, as we have seen on both European and national levels since the great recession of 2008-09.

The directive is a historic victory for European workers and all progressive forces in Europe. It represents a milestone in EU social policy and demonstrates that the European Pillar of Social Rights can provide a genuine compass for legal initiatives that improve the lives of millions of citizens.

But let’s not get carried away. The directive is no silver bullet to solve in-work poverty and wage inequality. It demonstrates a long-overdue shift in the dominant view on the role of minimum wages and collective bargaining—and even goes a step further by defining procedural rules which put the onus to enact improvement on member states. But it is now more than ever up to national policy actors to take the necessary political initiatives to increase minimum wages substantially and to strengthen collective-bargaining coverage.