Globalisation, immigration and changing cultural values are disrupting electoral politics across the world. The main beneficiaries of this disruption are populist, radical-right parties running on nationalist platforms. Survey evidence shows that what motivates people to vote for these parties are concerns about status. These concerns arise because large-scale societal and economic transformations challenge the traditional social order.

We know less about how nationalist parties and candidates succeed in benefiting from these concerns. How do they convince voters who are pessimistic about their future that nationalism is the answer?

In a recent study, we argue that nationalists address voters’ status concerns through both identity appeals to the nation and nationalist policy offers. Positive appeals to national identity motivate voters to think of themselves primarily as members of that nation, rather than a declining socio-economic class. Nationalist policies aim to improve a nation’s relative cultural and political status.

In propagating such policies, nationalists promise voters a future change in the social order that would benefit them as members of the nation. In line with the social psychology of status, we argue that nationalism so conceived will be particularly persuasive among voters in declining sectors of the economy, who can cling to the hope that they will see a rise in status as members of the nation.

Unique opportunity

Our case, imperial Austria’s first election after the full implementation of universal manhood suffrage in 1907, offers a unique opportunity to test these arguments. In that context, parties did not yet know which appeals would resonate among a mass electorate. Multiple nationalist parties tried out different appeals within the same electoral districts, under the same majority run-off electoral formula. These features allow us to draw much more clear-cut inferences about the effects of different appeals than is possible with contemporary elections, in which parties already have a record and where there is usually only one nationalist party per district.

Our analysis covers the electoral strategies of six German and six Czech nationalist parties. These parties aimed to mobilise the kingdom’s two largest and most industrialised national groups: Germans (36 per cent) and Czechs (23 per cent). Members of the rapidly growing industrial working class in provinces with Czech- and German-speaking populations may have been poor, yet they had good reason to be optimistic about their future status since, at the time, their economic sector was on the rise.

Simultaneously, many of these provinces’ voters belonged to the agricultural working class. Equally poor, agricultural workers were employed in a declining sector of the economy and thus had reason to be pessimistic about their future economic status. We can therefore effectively test how varying nationalist appeals resonated with status-optimistic and status-pessimistic voters respectively.

Though historically distant, Austria’s nationalist parties shared their core ideology of exclusionary nationalism with today’s radical-right parties. As today, they focused primarily on maintaining or raising their nation’s political and cultural status. To measure parties’ identity appeals and policy offers, we conducted a content analysis of parties’ election announcements.

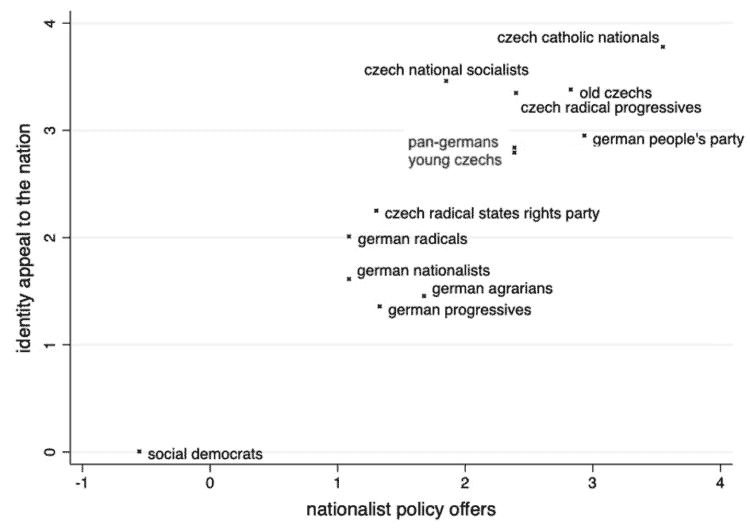

Parties published these announcements before elections in their own or ideologically affiliated newspapers, at a time when the press was quickly expanding. Figure 1 plots nationalist parties’ positive identity appeals to Czechs and Germans over how much they endorsed or denounced nationalist policies in their election announcements. The figure shows significant variation in strategy among nationalist parties. For comparison, it also includes the non-nationalist social democrats.

Figure 1: parties’ appeals to national identity and nationalist policy offers (1907)

How did these appeals fare among status-optimistic and status-pessimistic voters? To measure the share of the industrial and the agricultural working class among district voters, we draw on imperial Austria’s superb record-keeping. After the first election based exclusively on universal manhood suffrage, imperial bureaucrats conducted a study of all qualified voters’ occupations, allowing us to determine precisely how many voters in each district were agricultural or industrial workers.

Hierarchical regression analyses show that the more nationalist parties positively primed national identity, and the more they endorsed policies promoting the nation’s status, the higher their vote share. Interestingly, the effect of policy promises was bigger than that of identity appeal. This shows that thinking of nationalist parties only in terms of identity politics is inadequate.

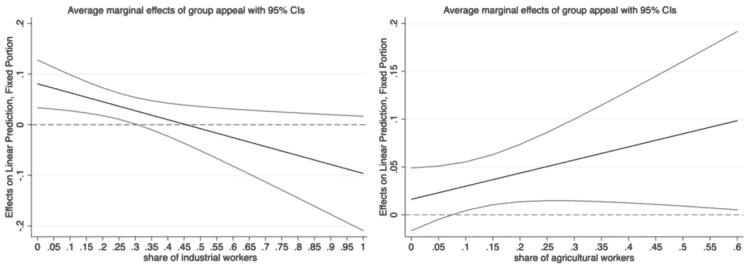

As expected, these campaign messages also resonated differently among industrial and agricultural workers. Figures 2-3 show how much nationalist identity appeals and policy offers boosted parties’ vote shares, conditional on industrial and agricultural workers’ share of the district electorate. The figures show that nationalist platforms were particularly successful in districts with a large share of agricultural working-class voters.

Figure 2: interactions between parties’ group appeal to the nation and the district electorate’s share of industrial workers and agricultural workers

Our results suggest that nationalist parties are particularly successful at capturing the votes of status-pessimists, while being much less effective among status-optimists. Though economically precarious, industrial workers had reason for optimism about the future status of their class and were a lot less susceptible to national identity appeals and nationalist policies.

By contrast, farm labourers paid in-kind or rural domestic workers, for example, were more likely to tie their status to the landed household to which they belonged, and thus to the traditional rural social order, than to be swayed by bold visions of building an industrial future. The rise of industrialism then, like the rise of post-industrialism now, threatened that status.

Status concerns

Although we studied imperial Austrian nationalist parties specifically, humans’ concerns about status are universal; in fact, they appear to be much older than concerns about money. We are evolutionarily hard wired to seek recognition. As social hierarchies evolve, some groups face a decline in status, others a rise. Navigating large-scale economic and societal transformation without losing considerable parts of the electorate to the nationalist radical right is thus a challenge for contemporary democracies, as it was a challenge for democratising imperial Austria.

From a normative perspective, it seems crucial that moderate mainstream parties respond effectively to this challenge. The German Social Democratic Party’s (SPD) 2021 election campaign can be seen as a successful example in this regard.

The party campaigned on a platform that promised to show respect for each societal group’s contribution to the common good and Olaf Scholz, its candidate for chancellor, appeared on large posters with the slogan ‘Respect for you’ (Respekt für dich). The SPD thereby effectively addressed voters’ need for social recognition, without succumbing to the exclusionary nativism of the radical right—a strategy which helped it attain a majority of votes and the chancellorship.

This first appeared on the EUROPP blog of the London School of Economics. For more, see the authors’ paper in Comparative Political Studies