It is striking how vocal and proactive the European Commission and other European Union institutions (such as the European Central Bank) have become on issues of European solidarity in recent years. The European Pillar of Social Rights of 2017 reflected a genuine commitment to enhance the social dimension of the single market and economic and monetary union. Since 2020, NextGenerationEU has promoted fiscal solidarity to overcome the aftershocks of the Great Recession and the pandemic, with quite assertive country-specific recovery-and-resilience plans.

This year has seen an even stronger resurgence of geopolitical solidarity in confronting Vladimir Putin’s war on Ukraine. Support for a more robust EU has also shone through the citizens’ panels of the Conference on the Future of Europe and the favourable political reaction to their recommendations. European solidarity has always been in high demand—but today, at long last, there is also fairly strong supply.

Finger-pointing

For sure, the treaties have always been replete with exhortations to solidarity, social cohesion, mutual assistance and so on. The preamble of the 1951 treaty establishing the European Coal and Steel Community claimed that ‘Europe can be built only through real practical achievements which will first of all create solidarity’.

Yet not long ago, such solidarity was meagre. The eurozone crisis turned into a ‘blame game’ between creditor and debtor countries, which left the burden of saving the euro to the ECB. The ‘refugee crisis’, similarly, triggered finger-pointing among frontline states, host states and uninterested bystander states. And calls for unity in security and defence policy met manifest disagreement on military spending and the pooling of defence equipment, technology and production.

The EU remains a political union of nation-states. To the extent that these are mature welfare states, they provide large swaths of support to national citizens bearing social rights. Generous domestic welfare inherently limits the political space for cross-border solidarity. But now that European solidarity is being leveraged by NextGenerationEU, the extent of public support, across member states, becomes critical.

Continuity and change

Since 2018, the European University Institute (EUI), in collaboration with the polling organisation YouGov, has conducted a yearly survey across member states of attitudes towards European solidarity, integration and defence. The ‘Solidarity in Europe’ project now takes in more than 23,000 respondents across 16 member states and the United Kingdom. The results are published annually on the EUI’s research repository.

Looking back on five iterations, among member states and across policy instruments we observe continuities and changes in popular support for solidarity. The point of departure of the survey was an expectation that public support for common solutions was low even though the cross-border ramifications of the multiple crises facing Europe since 2008 were strong. Low public support, in turn, fed into intergovernmental recalcitrance on issues of European solidarity.

We anticipated however that this could change—and change it did. We were particularly interested in finding out under what conditions political support for EU solidarity could be galvanised, rendering it politically salient, legitimate and an effective European instrument to mitigate adversity. We conceptualised European solidarity to vary by issue (solidarity for what?), by member state (solidarity by whom for whom?) and by instrument (solidarity how?).

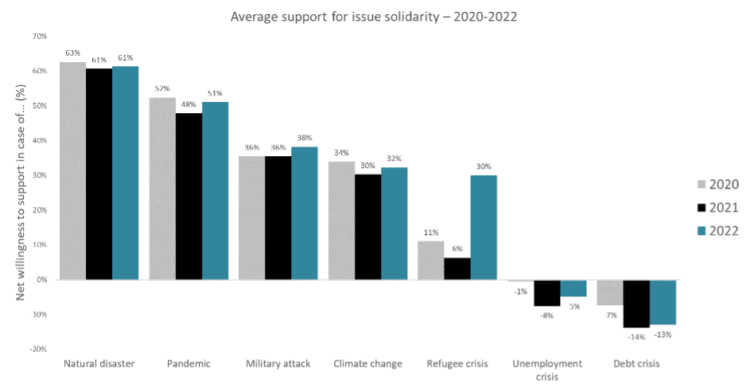

We theorised that external shocks (natural disasters, pandemics, wars) could elicit stronger solidarity than predicaments such as debt, unemployment and partly also refugee inflows —endogenous imbalances thought to be the member states’ own responsibility and thus less deserving of cross-border (fiscal) solidarity. This predisposition was stronger in some member states than others: countries with deep fiscal pockets were less likely to support solidarity to address public debt and unemployment crises; transit countries or countries far removed from main routes of migration were less likely to support solidarity on refugees.

These patterns indeed persisted throughout the project, though a blip came in 2022, when the Russian invasion of the Ukraine brought a significant rise in support for refugee-solidarity in its wake.

Self-reinforcing preference

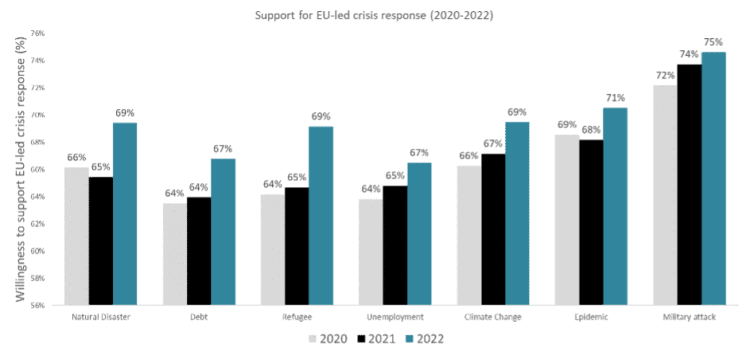

Another important initial hypothesis claimed that, once the imaginary Rubicon of tangible European solidarity was crossed, citizens would prefer contributing to an EU-led initiative to providing assistance to other countries on a bilateral basis. Since the onset of the pandemic in March 2020, the evidence has confirmed such a self-reinforcing preference for EU instruments to be at the helm of crisis management.

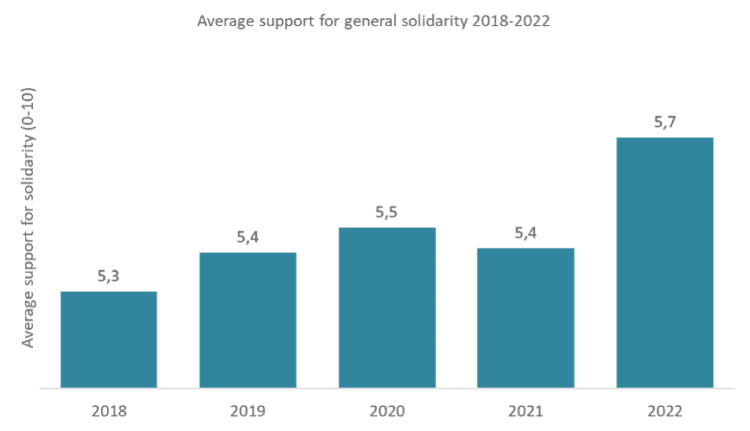

As an exogenous and symmetric shock, Covid-19 created the conditions we had believed conducive to building political capital for European solidarity. General support for solidarity was already quite high in 2020. But it remained stable during 2021, despite the stress of unprecedented steps towards fiscal solidarity, and is in 2022 much stronger than three years ago. Solidarity has thus been reinforced by the pandemic experience.

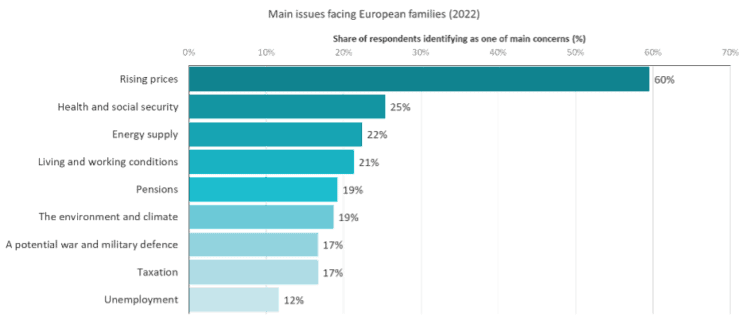

The 2022 figures can be read as representing popular support for EU-led crisis management, particularly NextGenerationEU—the main source of redistribution supporting Europe’s economic recovery. One would perhaps expect that the 2022 hike in solidarity is strongly related to Ukraine. Yet prices and energy supply (not unconnected, of course) are the main concerns for Europeans at this juncture, rather than the war itself.

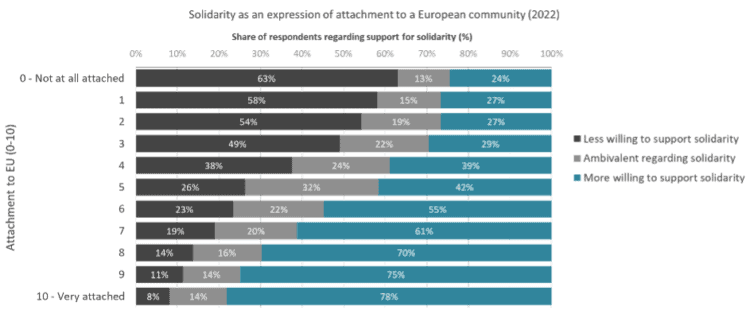

Exploring the correlates of European solidarity, we find a clear association with political attitudes towards the EU. Solidarity represents a willingness to engage collectively in the sharing of risks and resources against adversity. This implies the existence of institutional trust and a sense of belonging to a community—a European one. Is it far-fetched to see the combination of trust and solidarity as indicating an expression of community-building, towards something of a European polity (albeit without a well-defined demos)?

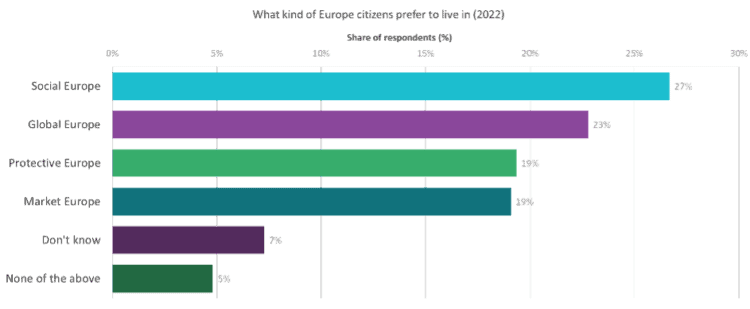

What kind of Europe do its citizens want? A ‘market Europe’ (stressing market integration and economic and monetary union) is less popular overall than a ‘social Europe’ (emphasising fair and equitable living standards) or a ‘global Europe’ (highlighting the EU’s leading role on climate and human rights). Most Europeans prefer a social model for Europe and the most supranationally oriented are also those most disposed towards fairness on welfare.

In combination with the finding that more citizens are willing to pay higher taxes for improved welfare, this indicates some scope for the EU to advance its social agenda. And under Ursula von der Leyen’s presidency the commission has been far more assertive than under José Manuel Barroso in the wake of the Great Recession, when solidarity was in very high demand but supply was dismal.

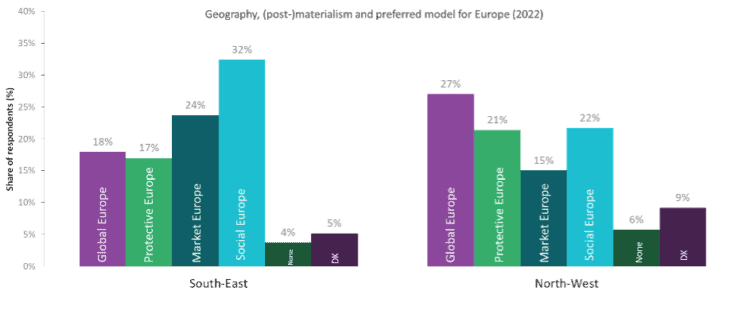

There is regional variation here. In north-western member states, where a global Europe is preferred, citizens sustain a more ‘post-materialist’ conception of the EU’s role in terms of international political values. In south-eastern states, though, citizens tend to view the EU through a more materialist lens, stressing a Europe that privileges social protection and market-based prosperity.

Nevertheless, the north-south rift over austerity, which characterised the eurozone crisis and its aftermath, may be easing. And the north-western versus south-eastern differences could form the basis for a vision for the EU as a whole, addressing different yet not antagonistic aspirations in tandem. Over the lifetime of this project, the EU has matured politically. This happened on the fly, in reaction to the multiple crises from eurozone debt to Putin’s war, rather than consciously and deliberately. What we seem to be witnessing are the growing pains of a political union with social fairness at its core.