Income inequality in the European Union is a bit tricky to determine. As a plurinational entity with 27 member states, its distribution across the whole EU depends on disparities among and within national economies, which evolve in different ways. To measure it correctly, one would need a single EU-wide sample.

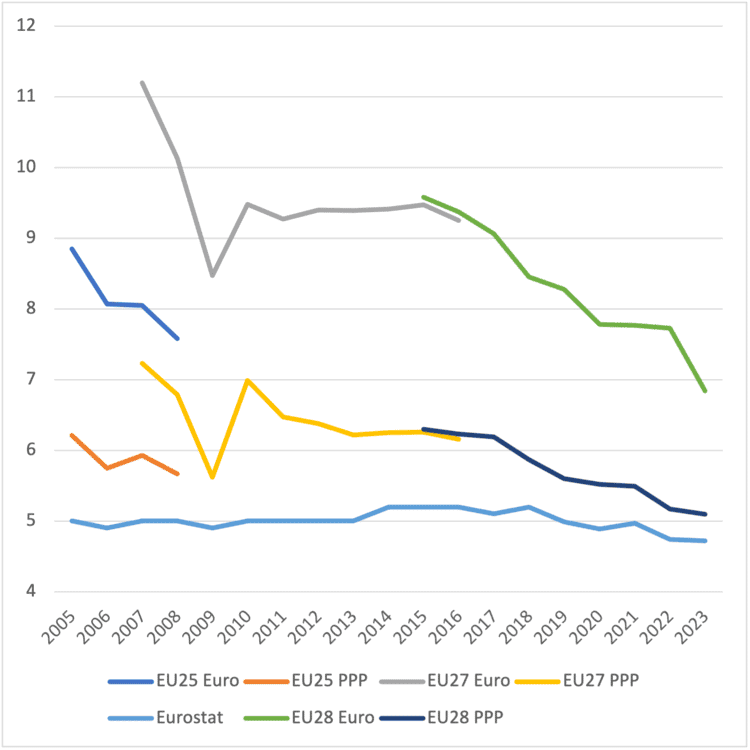

As an index of inequality, the quintile (S80/S20) ratio divides the income of the richest fifth of a population by that of the poorest. The best statistical data for this in the EU come from the Survey of Income and Living Conditions (EU-SILC). This is based on national surveys, covering thousands of households.

Many of the richest households in poor countries will belong to the 20 per cent richest across the EU and vice versa for the poorest. So the second-best measure of union-wide inequality, using the EU-SILC data for 2023, is to take the 135 (27×5) national quintiles, constructing the richest and poorest EU quintiles out of the top and bottom national ones.

A further complication is that gaps between member states are smaller when national incomes are compared at purchasing-power parities (PPP). This is because the same nominal income in euro, with an exchange-rate conversation for other currencies, results in a higher real income in poorer countries, given lower prices.

Figure 1 shows the thus-calculated EU-wide S80/S20 ratio, at PPP as well as euro exchange rates, with the former showing lower inequality. The lowest line in Figure 1 shows the value Eurostat derives. This by contrast underestimates the S80/S20 ratio, because it is calculated as the weighted average of the national ratios and so neglects the income discrepancies between countries altogether. Its relatively stable value (about five) reflects the fact that, on average, income distribution within member states has not changed much over the last 20 years.

Figure 1: EU-wide inequality 2005-23 (S80/S20 ratios)

Inequality decreasing

The EU-wide S80/S20 ratio has declined substantially since the eastern enlargement of 20 years ago (with the second round in 2007, when Bulgaria and Romania joined). This convergence has been driven primarily by the higher growth of the poorer member states in central and eastern Europe (CEE). Measured at PPP, this curve is now converging on the (distorted) Eurostat value—which means that class increasingly trumps country as the primary cause of a household’s position in the EU income pyramid.

EU-wide inequality has continued to decrease in recent years, in spite of the various crises Europe has been facing, such as the pandemic and the Ukraine war, with the subsequent inflation and energy crises. Even the attenuated Eurostat S80/S20 ratio shows that, during these crisis times, inequality has declined in most countries. The same is true of poverty (not shown here).

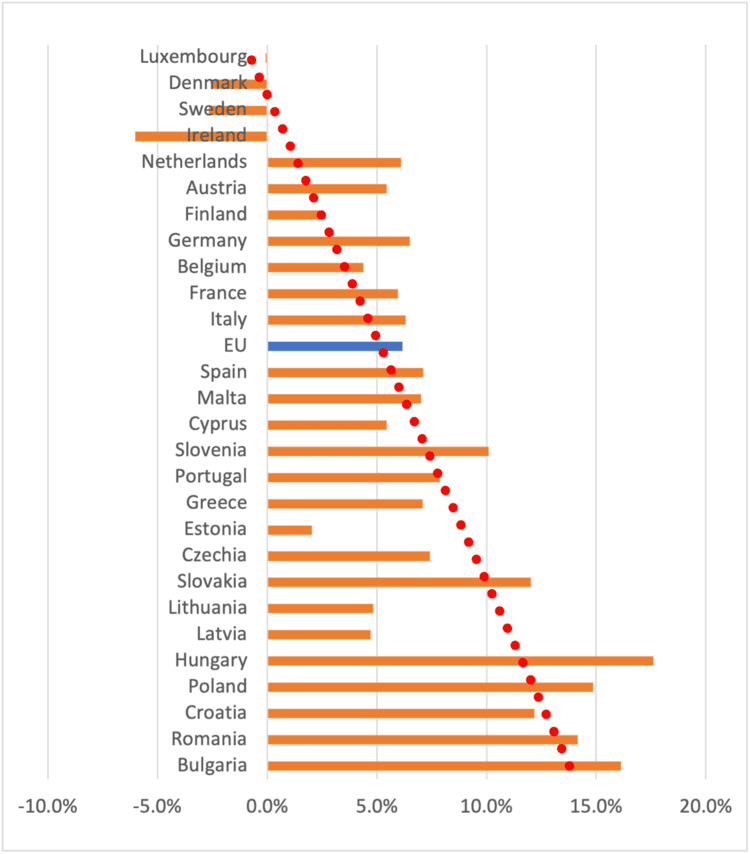

In 2022, as my last analysis showed, convergence among member states improved as both the poorer peripheries, in the south and the east of the EU, benefited from higher growth than the rich north-west. This trend strongly continued in 2023.

Figure 2 presents national growth rates of gross domestic product per capita between 2022 und 2023, ordered by GDP per head in 2014, with the richest country (Luxembourg) at the top and the poorest (Bulgaria) at the bottom. The red-dotted trendline shows (some outliers excepted) that the poorer a country has been historically the stronger was its growth in 2023.

This relative catch-up is an almost perfect case of what economists call ‘beta convergence’. It does not necessarily imply falling absolute income disparities (‘sigma convergence’ or a decreasing standard deviation in per capita GDP). Nonetheless, this overall convergence indicates that the generous response of the EU during the ‘polycrisis’ has led to a much more favorable outcome than the terrible austerity policies pursued after the financial crisis in 2008-10.

Figure 2: growth of GDP per person in 2023

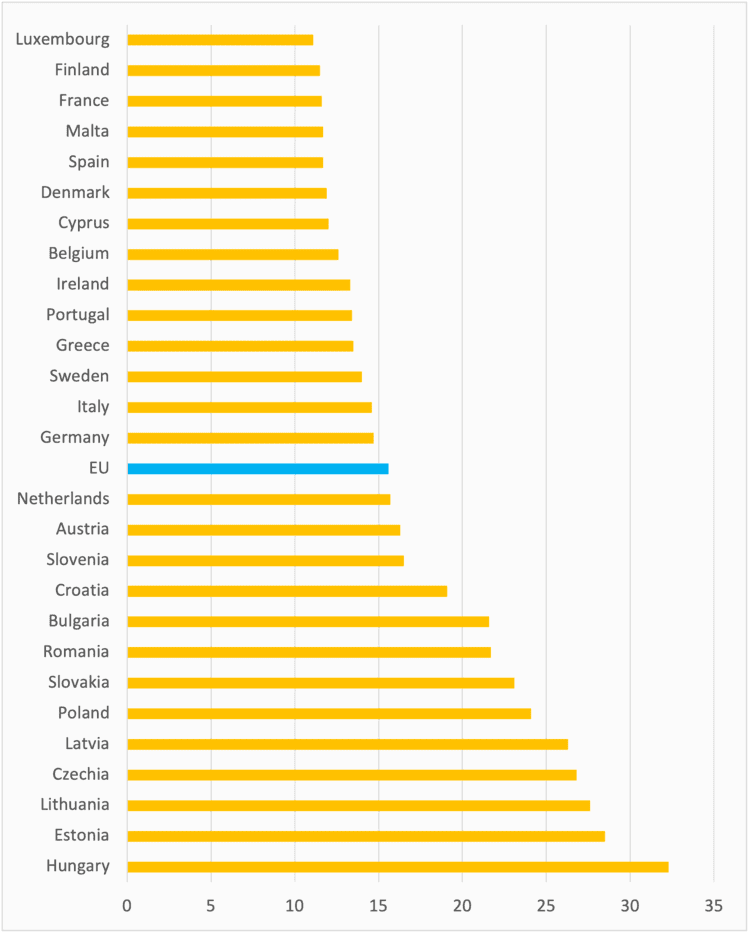

High inflation

There is, however, a blemish in this encouraging picture. The strong CEE growth has been accompanied by high inflation since the beginning of the Ukraine war. While the combined inflation of the two years 2022 and 2023 was 16 per cent for the whole EU, most CEE countries suffered from totals well above 20 per cent (Figure 3).

Figure 3: inflation (HICP) 2022+2023 (%)

Higher inflation (and/or an appreciation of the currency in member states that have not yet adopted the euro) is however an unavoidable dimension of catch-up growth. Otherwise, the incomes of those working in the non-tradeables sector, such as barbers or teachers, would never rise to the levels of richer countries.

The discrepancy between incomes at PPP and exchange rates is mainly due to the lower prices of services (and rents) in poorer countries. This will erode during the catch-up process, as the prices of these services rise more quickly than in the richer parts of the EU (the ‘Balassa-Samuelson effect’).

During the eurozone crisis, the countries suffering from sovereign-debt panic, such as Greece, were blamed for unsustainable inflation undermining their international ‘competitiveness’. Austerity measures were enforced to bring about an ‘internal devaluation’ (in the context of a common currency), via lower wages, because unit labour costs were deemed too high.

Is CEE facing a similar crisis? As with inflation generally, unit labour costs are growing there much more strongly than elsewhere in the EU. But in most CEE countries current-account balances and government debt hardly give reasons to worry for now.

Progressive policies

As the Eurostat trend line showed in Figure 1, income inequality within member states decreased in 2023 (as in 2022), with the S80/S20 ratio declining, on average, from 5.2 in 2018 to 4.7 latterly. The incidence of poverty also fell, more marginally, from 16.8 per cent in 2021 to 16.2 per cent in 2023.

The picture becomes somewhat bleaker if we look at material deprivation—lack of fulfillment of various basic needs—which increased from 7.2 per cent in 2021 to 9.1 per cent in 2023. In the context of high inflation, even improved nominal incomes may not ensure acceptable living conditions.

Still, the recent decline in inequality shows progressive policies can make a difference. Within countries, income support, targeted subsidies and expansionary fiscal policies have kept unemployment low and sustained demand, growth and wages. On the EU level, the big NextGenerationEU project broke with the austerity bias that had informed European economic policy for decades.

Yet on both levels, national and European, a backlash threatens. The EU is focusing once more on the vague concept of competitiveness and might again expose national budgets to the vagaries of volatile capital markets and greedy speculators. In some member states, such as Germany, old narratives about the welfare state threatening growth and competitiveness are revived. A renewed focus on fiscal ‘discipline’ will impede the investments needed to prevent catastrophic climate change and secure sustainable welfare and social cohesion.

Michael Dauderstädt is a freelance consultant and writer. Until 2013, he was director of the division for economic and social policy of the Friedrich Ebert Stiftung.