Inequality is a key topic in social science and politics, and with good reason. Too high inequality can weaken social cohesion and societal welfare. Globalisation, digitalisation and financialisation tend to shift the balance of power between employees and employers ever more towards the latter, bringing more inequality and polarisation, as well as greater uncertainty for workers.

In looking at these large global trends, however, we sometimes lose sight of the complexity of inequality and how it varies across countries and time, overlooking what can be offsetting country-specific institutions and factors. Across the European Union over the last two decades, inequality has in fact declined. Even in the United States, where inequality seemed destined to keep inexorably growing, there has been a turnaround associated with rising demand for labour and so greater bargaining power for workers.

Key factors

A recent working paper by the European Trade Union Institute takes a closer look at wage inequality across Europe. In particular, it focuses on how institutional specificities and high demand for labour can strengthen the bargaining power of workers in wage distribution, thus counteracting the large-scale trends that have undermined workers’ bargaining positions over time. Understanding how these key factors still support especially lower-wage workers in the EU is crucial when thinking more widely of ways to reduce wage inequality.

Cross-nationally comparable data on wages for the active population during 2006-21 in 25 EU member states (not Malta or Cyprus) are drawn from the EU statistics on income and living conditions (EU-SILC). The spread in these wages is linked to institutional and economic factors affecting workers’ bargaining position: the impact of the minimum wage when compared with the average (the Kaitz index), the share of workers covered by multi-employer collective pay agreements as distinct from firm-level agreements and union density as an indicator of the strength of trade unions. Unfilled vacancies within specific sectors as well as unemployment vis-à-vis demographic characteristics are trawled to capture labour shortages and demand.

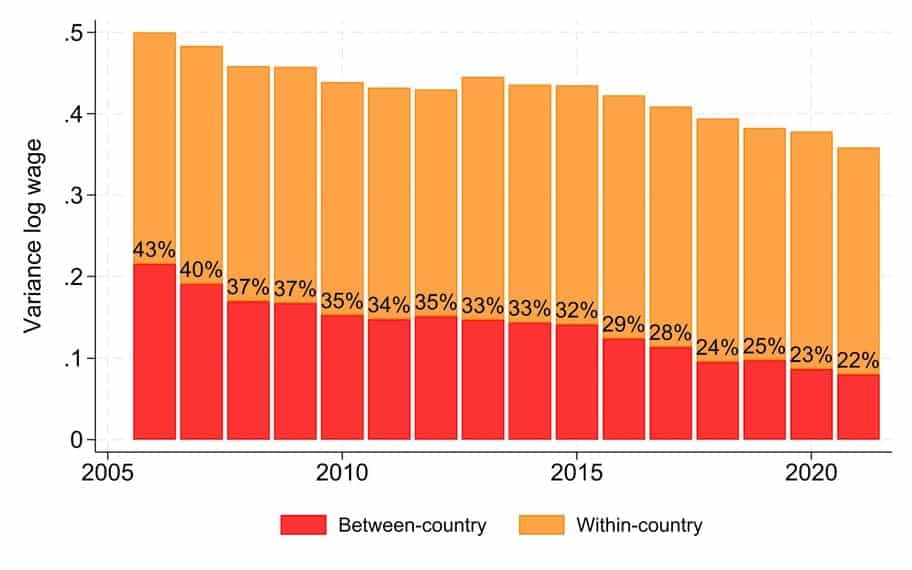

Wage inequality across the union as a whole has declined substantially over time (Figure 1). The variance of wages dropped by about a quarter (28 per cent) between 2006 and 2021. Average inequality within countries remained relatively stable, although it declined slightly over this period in most member states, but the differences between countries declined by almost two thirds (63 per cent). Such convergence is good news: it means the union as a whole is becoming more equal. Differences between countries do however remain very high when compared, for instance, with differences between states in the US.

Figure 1: wage inequality declining across the EU as a whole

Variation across countries

Inequality varies a lot among countries, in its levels and patterns (including by industry), and over time. Thus while wage inequality fell across EU countries in 2006-21 by about 11 per cent on average, it increased in six of the 25 member states. Indeed, in Italy and Spain, it rose by about 36 per cent.

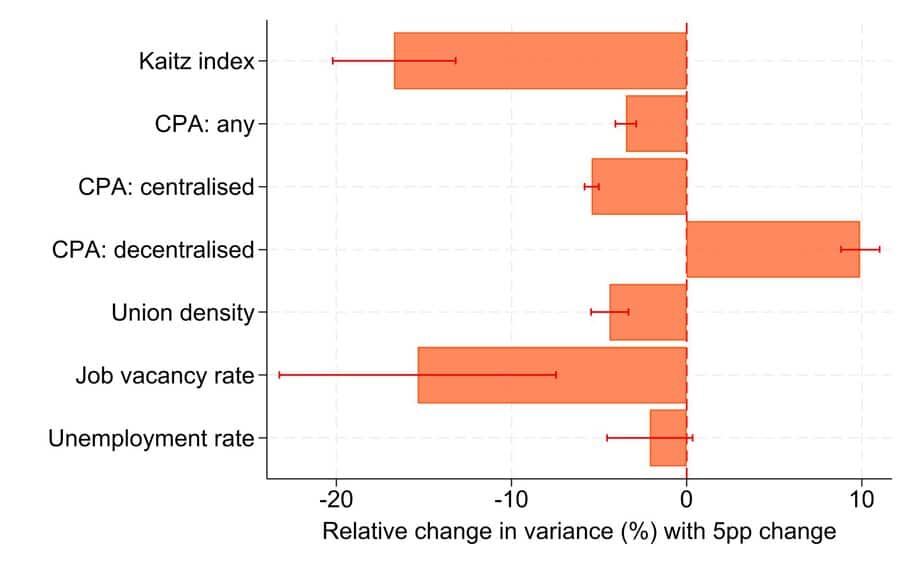

Analysing these differences (Figure 2), the spread of wages is narrower in those countries and years where the minimum wage—if there is one—has more impact. It plays a very substantial role, as it raises wages over the whole distribution but particularly at the lower end.

In those countries and sectors where more workers are covered by multi-employer collective pay agreements, wages are also more compressed; this is particularly important for the lower half of the wage distribution. Higher union density has a similar effect. Decentralised, firm-level agreements, however, are associated with wider spreads, possibly because divergences in profitability between organisations are carried through into wage differences.

Institutions are not though the only important factor—the higher demand for workers associated with labour shortages also tends to lower inequality while raising wages. This points to the importance of bargaining position: as the choices and outside options of workers improve, so do their wages, and this tends to compress the distribution.

Figure 2: institutional and economic factors affecting the distribution

Collective-bargaining coverage

The European system of strong institutions does set a wage floor and provide support for workers, which contributes strongly to relative wage equality. Over time, however, coverage by collective agreements has been declining while trade unions have weakened.

This highlights the importance of the stipulation in the EU minimum-wages directive that member states where collective-bargaining coverage is below 80 per cent should produce national plans to address that shortfall. The research also make clear that an effective minimum wage does set a sound wage floor while compressing the distribution. Besides strong institutions, moreover, it further suggests a silver lining to current labour shortages—that they increase workers’ bargaining power and can lead to better pay and conditions.

Rising wage inequality is not, therefore, an inevitable consequence of new technologies or globalisation, to be fatalistically accepted. EU and national policies and labour relations still have a large impact on how wages, and their distribution, evolve.