Over recent months, the active role of digital platforms in the Ukraine war has come to the fore. In October, the sudden shutdown of Starlink—the Space-X satellite system providing internet access to civilians and military personnel—almost jeopardised a decisive military operation in the east of the country. A month later, Elon Musk, owner of Space-X and now Twitter, was reported to have talked with the Russian president, Vladimir Putin, before tweeting out his ‘peace plan’ for Ukraine (Musk denied the claim).

In June, Amazon Web Services—the company’s cloud division—disclosed that on February 24th, the day the invasion began, its technical staff met representatives of the Ukraine government to discuss bringing Amazon storage hardware into the country to transfer public- and private-sector data to the cloud. The same goes for Microsoft. In November it committed to providing $100 million worth of technology ‘to ensure that government agencies, critical infrastructure and other sectors in Ukraine can continue to serve citizens’ via its cloud.

Is this a ‘privatisation’ of war? Yes and no. On the one hand, nation states—with their armies, paramilitary forces and intelligence agencies—remain the main (deadly) warfare actors. On the other, the active role played by a handful of digital platforms marks an important discontinuity with the past.

Techno-economic power

Becoming strategic actors in warfare, platforms are unveiling a new and under-investigated side of their techno-economic power. A mutual dependence binds nation states to them.

States can hardly any longer pursue their objectives without the data, technology and infrastructures platforms control. Engaging in intelligence activities, utilising remote-controlled digital weaponry, prosecuting or resisting cyberattacks—none of this can be accomplished if platforms do not provide active support.

By controlling vital infrastructures, such as the cloud and submarine cables, platforms become nation states’ ‘eyes and ears’ (at home and abroad), as well as unavoidable interlocutors when states exploit weaponised interdependence in international relations. Their technological dependence is magnified by the complexity and cumulative character of digital knowledge, as well as by the dual, civil-military uses and ‘black-box’ nature of the critical technologies platforms monopolise, such as big data, machine learning and artificial-intelligence algorithms.

In turn, global platforms need government support to circumvent internal and external obstacles to their expansion: regulations limiting access to personal data, hostile actions by antitrust or fiscal authorities, foreign governments opposing their investments or unions fighting to obtain higher wages and better working conditions. Platforms’ economic value is strongly correlated with the size of the network and amount of information they control, so legal and institutional barriers hindering such expansion can threaten their accumulation capacity.

As platforms however assume the role of indispensable partners for security and military activities—as well as accounting for a major share of gross domestic product—it becomes quite unlikely governments will disturb their expansionary strategies. Likewise, military procurement represents an increasingly important source of accumulation and a crucial demand-side driver for platforms pursuing high-uncertainty research-and-development and innovation projects.

Boundaries blurred

Such mutual dependence reinforces platforms’ economic power. On top of their lobbying activities and capacity for retaliation, this makes it easier for platforms to align government policies with their own strategies. It blurs conventional state-market boundaries, vindicating forgotten traditions of economic thought—such as the ‘new liberalism’ of John Hobson’s early 20th-century Imperialism or the 1960s Marxism of Monopoly Capital by Paul Baran and Paul Sweezy—emphasising the convergence between monopolistic power and nation states’ military strategies for dominance.

The mutual dependence between platforms and governments is specifically related to the mounting tensions between the United States and China. They are not only competing for economic and geopolitical domination but are also the homelands of the global platforms—such as Amazon and Microsoft, Alibaba and Tencent—dominating the digital sphere.

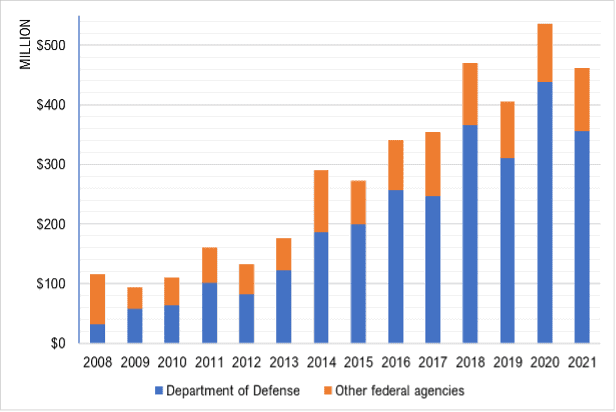

The state-platforms nexus can be explored more fully using procurement and spending data. The monetary value of military (and security) procurement contracts awarded by the US Department of Defense (DoD) and other federal agencies to the four major domestic platforms—Amazon, Google, Facebook and Microsoft—grew steadily between 2008 and 2021 (see chart). Indeed, this growth was exponential in multi-year contracts for key technologies and infrastructures (see table).

Value ($m) of Amazon, Google, Facebook and Microsoft contracts with the DoD and other federal agencies

Selection of multi-year military and security contracts awarded to major US digital platforms

| Year and department/agency | Contractor | Value ($) | Nature of service | Declared aim |

| 2013—Central Intelligence Agency | Amazon | 600 million | Cloud | Data management aimed at preventing terrorist attacks |

| 2019—Department of Defense | Amazon and Microsoft | 50 million | Drones | Defence |

| 2020—CIA | Alphabet, Amazon, Microsoft and Oracle | Not available | Cloud | Commercial Cloud Enterprise (C2E)—cloud services centralised for 17 intelligence agencies |

| 2021—DoD | Microsoft | 21.9 billion | Augmented reality visors | ‘HoloLens augmented reality headset’ for military activities in highly complex contexts |

| 2022—National Security Agency | Amazon | 10 billion | Cloud | Cloud infrastructures for NSA |

| 2022—DoD | Amazon | Not available | Start-up accelerator | Coordination of innovative activities and promotion of start-ups of military relevance |

| 2022—DoD | Microsoft | Not available | Stryker armoured vehicles | Digital devices to be incorporated into armed vehicles |

| 2022—DoD | Alphabet (Google public-sector division) | Not available | Google workspace | Provision of Google Workspace to 250,000 DoD employees |

| 2022—DoD | Alphabet, Amazon, Microsoft and Oracle | 10 billion | Cloud | Cloud infrastructure for the ‘Joint Warfighting Cloud Capability’ |

In line with evidence provided by Lucas Maaser and Stephanie Verlaan, this suggests that the US military apparatus is increasingly dependent on platforms’ technology, knowledge and critical infrastructures. Along similar lines, Cecilia Rikap and Bengt-Åke Lundvall have shown that more than 80 per cent of AI-related patents are held by US and Chinese digital corporations.

Such dependence grows as the amount of data under platforms’ control increases and the related technological processes, such as machine-learning algorithms, become more impenetrable. Platforms are essential for the operation of the internet and, consequently, for the functioning of markets, the production and delivery of public goods and, as indicated, key military and security activities.

At the same time, the resources provided by the DoD and other federal departments become more and more important to platforms, in monetary terms and as innovation drivers. Making weapons (or digital components and counterparts) has become a relevant platform activity. Top platform representatives are peppering public institutions aimed at developing and controlling military-related technologies.

Take Eric Schmidt, former chief executive of Alphabet. Together with the veteran former secretary of state Henry Kissinger and former deputy defense secretary Robert Work, Schmidt is a member of two government advisory boards seeking to jump-start technological innovation at the DoD. At the same time, he has relied on his own venture-capital firm, and $13 billion fortune, to invest in more than six defence start-ups.

Worrisome development

Although contradictions and conflicts are always in play, this mutual dependence between states and platforms points to relative convergence of their expansionary strategies—convergence enhanced as platforms become key players in pursuing military and security objectives. As in 1902, when Hobson’s Imperialism appeared, these strategies are intertwined due to the continuous search for new accumulation opportunities, data and technology to control, infrastructural interdependence to be weaponised and geopolitical domination to be wielded.

This is not necessarily a new development but it is worrisome. It renders the boundaries between states and markets fuzzier and puts in question the willingness—even the ability—of the former to regulate and discipline the latter in the collective interest. Control over vital dual-use technologies and infrastructures may moreover allow platforms, and corporations in general, to align governments’ strategies with their own. Finally, this confirms the risk of subordinating the production of knowledge and innovation to such corporate strategies and their disturbing linkages with those pursued by military apparatuses.

An earlier version of this article was published in Italian on Il Menabò di Etica ed Economia