In the lead-up to the 2019 European Parliament elections, young people across Europe took to the streets, demanding more ambitious climate policies to secure their future. Their protests ultimately paved the way for a legislative term defined by the ambitious European Green Deal.

Five years on, climate-related protests are again making waves ahead of elections to the parliament—but the tone has shifted. In several European Union member states, farmers have been rolling their tractors into capitals to voice their frustration about environmental regulations, sparking concerns that the EU’s green agenda could lose its political momentum.

Quick to capitalise on these protests, far-right populist parties are calling for a reversal of climate policies, portraying them as overly burdensome for ordinary citizens and farmers. In tandem with surging far-right support in national polls, their narrative of widespread climate fatigue has gained traction.

This has led to a growing reluctance among liberal and centre-right politicians to endorse Green Deal initiatives, calling instead for a pause on climate legislation in response to what they seem to perceive as a broader shift in public sentiment. In an apparently hurried attempt to quiet the farmers’ blaring horns in the run-up to the elections, the European Commission even proposed to slash environmental standards that determine eligibility for funding under the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP).

Widespread climate concern

But does this political U-turn truly reflect the public mood? Survey data collected by the Jacques Delors Centre from 15,000 citizens in Germany, France, and Poland indicate otherwise. Amid a heightened cost of living, a challenging economic context and Russia’s war in Ukraine, continued climate action remains salient to a broad range of voters.

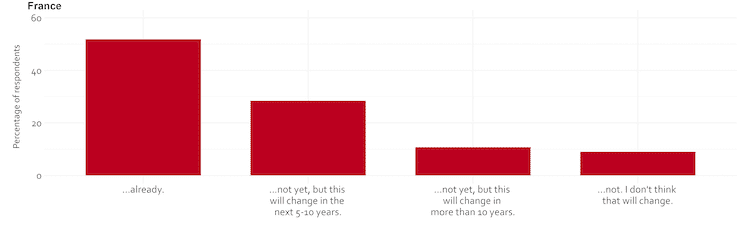

Rolling back years of climate legislation would clash with widespread concern among citizens as to the impacts of climate change on themselves and their families. In Germany and Poland around 60 per cent of those surveyed said that they were already negatively affected by climate change or expected to be so in the next five to ten years. In France this proportion even reached 80 per cent (Figure 1).

Figure1: ‘The negative effects of climate change affect me and my family …’

As such, when questioned on whether existing climate policies were overly ambitious or needed to be intensified, a majority—57 per cent in France, 53 per cent in Germany, and 51 per cent in Poland—favoured more action. Notably, this consensus extended beyond the core of green and left-leaning party supporters, with advocates of increased climate ambition outnumbering sceptics across almost all political affiliations in the three countries, including among liberal and conservative voters.

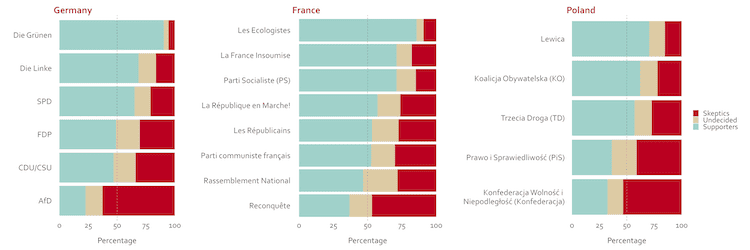

That said, a sizeable minority of respondents were sceptical towards more ambitious climate policies in all three countries surveyed. It amounted to roughly 30 per cent of the population in Germany and Poland and slightly less in France (23 per cent). Yet, there is little evidence that this group has grown significantly in recent years or that such scepticism is primarily rooted in tough material concerns, as is often claimed. Rather, we found a strong link to political partisanship: supporters of far-right parties were markedly over-represented in this group (Figure 2).

Climate scepticism thus does not appear to be a prevalent phenomenon within the political mainstream. Therefore, democratic parties should not rush into a ‘race to the bottom’ in scaling back their climate ambitions.

Figure 2: General attitude towards climate policy in Germany, France and Poland—supportive or sceptical

Voters’ policy priorities

The survey shows that mainstream voters still favour a raft of concrete climate measures over a freeze on policy initiatives. This does not though diminish the importance of carefully selecting, designing and framing specific policies to maintain the climate consensus.

Whereas the tale of a broad green ‘backlash’ is largely overstated, voters have clear preferences on how the climate-policy mix in the EU should be shaped going forward. Aligning with these preferences will be particularly relevant to keeping liberal and conservative voters on board. Two main priorities stand out.

First, there is widespread support, across countries and party lines, for a stronger focus on green investments and industrial policies. Voters are supportive of subsidies fostering the manufacture of clean technology or the greening of established industries, particularly if public money comes with strings attached to ensure that investments also benefit workers and structurally weaker regions. Not all EU member states have however the fiscal firepower to finance these policies on their own and national solo efforts run the risk of fuelling economic divergence and unfair competition.

A well-coordinated European investment initiative could overcome these challenges and capitalise on synergies across countries—for instance, when it comes to highly popular investments in green infrastructure, including electricity grids and rail systems. Yet policy-makers must convey the necessity of strengthening the EU’s governance and spending power for joint green investments to achieve broader objectives such as economic resilience and convergence. Highlighting these priorities during the coming electoral campaigns, the survey indicates, would strike a chord with voters in the middle of the political spectrum.

Secondly,some policies necessary to fight climate change are relatively unpopular— particularly broad regulatory measures and price-based instruments, in areas such as housing and transport, where households will be directly affected by higher prices for fuel and energy. As the European Emissions Trading System is set to be extended specifically to these areas in 2027, vulnerable households with low or medium incomes, without access to appropriate public transport or in ill-insulated buildings, will be exposed to greater risk of hardship. Our findings underscore that accruing societal approval for these measures will only be feasible if emissions revenues are utilised to provide some form of compensation to all citizens while privileging those hit hardest.

Although the establishment of the Social Climate Fund (SCP) in 2026 will mark a relevant step, the financial means required to enable vulnerable households to afford necessary green investments—such as insulation measures, heat pumps or solar panels—will surpass the allocated resources. Without a more substantial redistribution of carbon-price revenues to households, the EU and member-state governments will inevitably offer targets for the far-right’s exploitation of grievance.

Reassuring citizens

As a new set of policy-makers takes charge, it will be crucial to reassure citizens that the costs and benefits of this transition are equitably distributed. Achieving this necessitates a comprehensive just-transition policy framework, beyond current fragmented policies limited in scope and scale. Importantly, this will require a revamp of the next EU budget, to allocate well-targeted support to transitioning regions, enterprises and workers and to households most in need.

Those campaigning for (re-)election in June should refrain from fanning the narrative of a green backlash. Instead, parties should compete on the best mix of green-investment and just-transition policies to address the EU’s regulatory imbalance. While implementing transition policies will entail significant costs and require political stamina, succumbing to calls for a rollback on climate action would misdiagnose where voters stand on the issue—and ultimately prove more costly.

The survey findings are presented in more detail in ‘Debunking the Backlash—Uncovering European Voters’ Climate Preferences’, by Tarik Abou-Chadi, Jannik Jansen, Markus Kollberg and Nils Redeker. The data can also be explored through an interactive dashboard.

Jannik Jansen is policy fellow for social cohesion and just transition at the Jacques Delors Centre in Berlin.